GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

Despite an underwhelming finale, FIONA O CONNOR relishes a vivid exploration of the Cinecitta of Pasolini and Fellini at their height

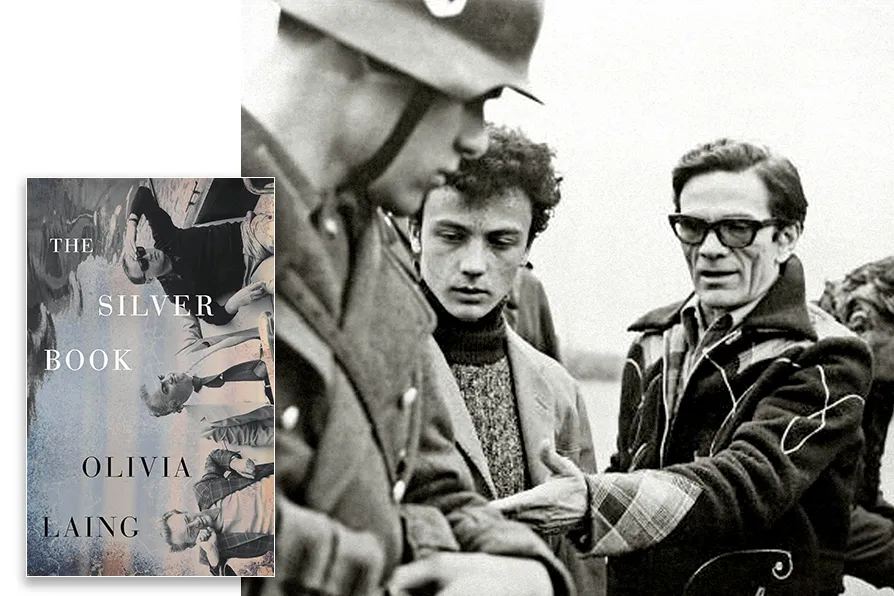

Pier Paolo Pasolini and Maurizio Valaguzza during the filming of Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975) [Pic: IMDb]

Pier Paolo Pasolini and Maurizio Valaguzza during the filming of Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975) [Pic: IMDb]

The Silver Book

Olivia Laing, Hamish Hamilton, £9.99

THIS is a gorgeous book – elegant and lucent, filmic in style: the writing thin as a reel of celluloid passing through a projector, but resonant and dealing with the most serious world issue erupting currently – fascism.

The Silver Book draws from the 1970s flowering of creative genius in Italian film-making to create a noirish thriller-ish conceit involving a fugitive art student, redhead Nicholas, escaping a tight spot he’s got himself into in London.

He bolts to Venice. The story glides into faction when Nicholas is picked up by real-life costume and set designer Danilo Donati, there researching for Federico Fellini’s next project, Casanova.

Through the developing love affair between Nicholas and Danilo the novel gains access to the creative worlds of two very different films in the making – Fellini’s Casanova, and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo. The outsized personalities of these visionary geniuses make cameo appearances as Danilo prepares sets and makes costumes, assisted by guilt-ridden Nico.

Olivia Laing’s writing is deft in conveying a vivid sense of the personae of these directors, particularly that of Pasolini. If Pasolini is a Christ-like figure, suffering the children, most comfortable among the abject (there are also fairly tame mentions of his predilections for young “hustler” men), then Fellini is God: huge and terrifying, irrefutable and ultimately unknowable.

Pasolini’s infamous film Salo is based on De Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom. The film utilises sexual perversity as metaphor for exploring fascist power in the last days of Mussolini’s reign. As depicted by Pasolini, fascism is alive and kicking beneath the surface of his contemporary Italy.

The Silver Book enters the craft world of this film, deliciously evoking the quotidian, careful labour involved in casting, rehearsing, supporting actors, dressing them and then shooting scenes involving rape, murder, and the forced eating of faeces. Salo is commonly listed among the most controversial films ever made. It was to be Pasolini’s last film before he was murdered in 1975.

The book dovetails the depiction of Pasolini’s last days with the outrageous, florid, magnificent attempt to create Fellini’s movie Casanova. Through scenes involving Fellini’s sadistic cruelty towards his leading man, a disciplined Donald Sutherland, it emerges that both films share a theme. Liberty – the artistic freedom of wilful excess in pursuit of deeper truths, in flagrant defiance of constraints — is an underlying philosophical stand.

This seems deeply relevant in the current onslaughts on freedom of expression and much else, seen under Trump in the US, and seeping into societies across Europe, not least in Meloni’s neofascist Italy.

The Silver Book, in its luminous representation of a bustling Cinecitta, shows the human striving behind the screened illusion. It is a depiction of friendship and betrayal, high aesthetics and basic drives, fascism and liberalism, collaboration and the mystery of individual inspiration.

A brilliant book in part, it sadly fails to meet the demands of a satisfying ending. The last section of the book can’t transcend the factitious set up. It dodges its artistic obligation, goes out less with an explosive force of imagination, a la Pasolini and Fellini, more like a damp squib.