John Wojcik pays tribute to a black US activist who spent six decades at the forefront of struggles for voting rights, economic justice and peace – reshaping US politics and inspiring movements worldwide

[Olha Schedrina/The Natural History Museum/CC]

[Olha Schedrina/The Natural History Museum/CC]

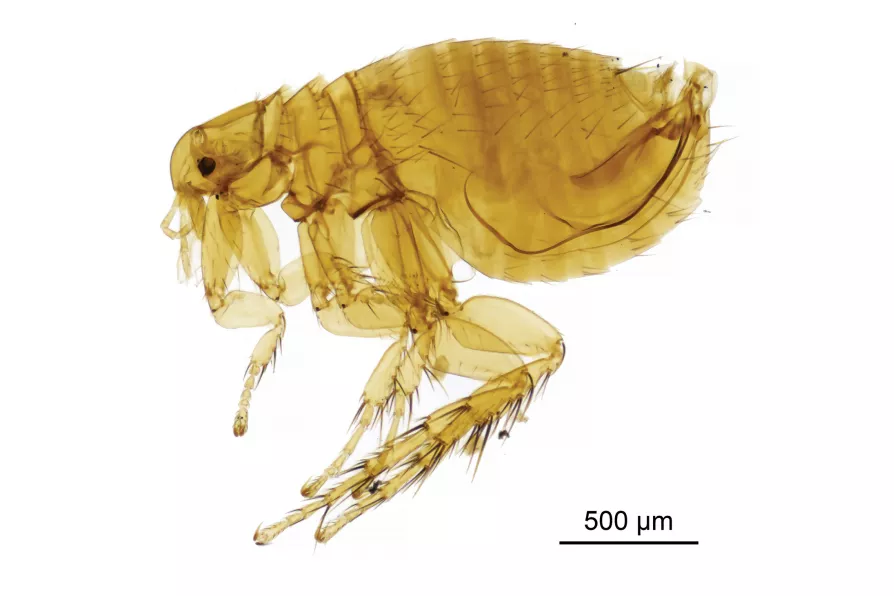

FLEAS are flightless parasitic insects that live from drinking the blood of animal hosts. They can jump huge distances using their powerful back legs, allowing them to transfer between hosts.

Many species of flea are named after a specific host, such as the “cat flea” (Ctenocephalides felis), but are in fact capable of feeding on several different animals.

As one of the Science and Society authors recently found out from moving into a new house, fleas lurk in carpets and soft furnishings while waiting for a new host. Once bitten, the host will have itchy, red bites.

Neutrinos are so abundant that 400 trillion pass through your body every second. ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT explain how scientists are seeking to know more about them

New research into mutations in sperm helps us better understand why they occur, while debunking a few myths in the process, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

ALEX DITTRICH hitches a ride on a jaw-dropping tour of the parasite world

A maverick’s self-inflicted snake bites could unlock breakthrough treatments – but they also reveal deeper tensions between noble scientific curiosity and cold corporate callousness, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT