GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends an important, if dispiriting book about the neo-colonial culture of Uganda under Yoweri Museveni

BETH DRISCOLL points out the value of print books in community culture and the barbarism of destroying libraries in Bosnia, Ukraine and Gaza

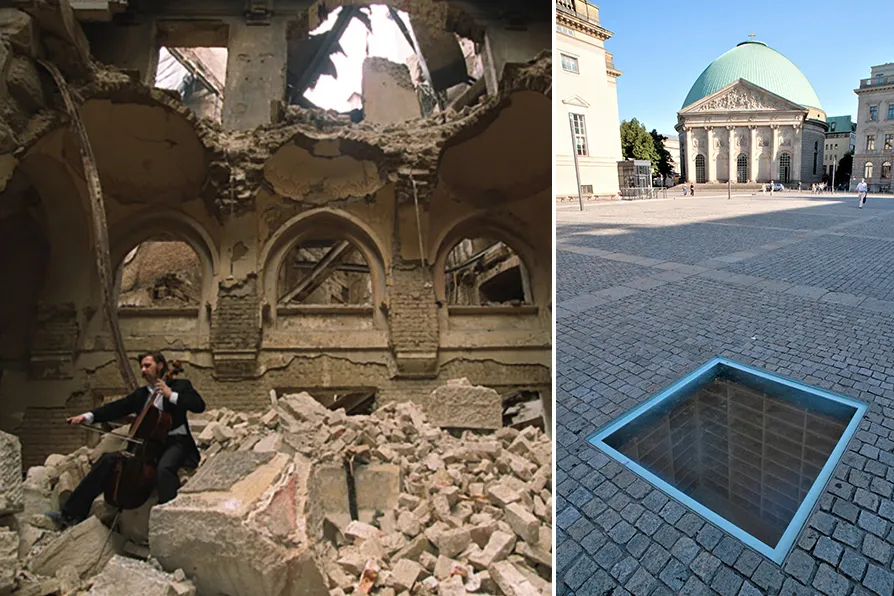

IN MEMORY OF BOOKS: (L) Local musician Vedran Smailović playing in Sarajevo in the partially destroyed National Library, 1992; (R) Memorial to Nazi-era book burnings at Bebelplatz in Berlin, Germany. [Pics: Mikhail Evstafiev/CC; Stefan Kemmerling/CC]

IN MEMORY OF BOOKS: (L) Local musician Vedran Smailović playing in Sarajevo in the partially destroyed National Library, 1992; (R) Memorial to Nazi-era book burnings at Bebelplatz in Berlin, Germany. [Pics: Mikhail Evstafiev/CC; Stefan Kemmerling/CC]

EBOOKS have been popular for decades and audiobooks are increasingly so. But physical books are still the decided favourite: a survey of Australian publishers after last Christmas reported print books made up a comfortable majority of sales (ebooks were 4–18 percent and audiobooks 5–15 percent). This is despite regular warnings about the death of the book.

Some critics of print books have even changed their tune. “We need to get over books,” wrote journalist Jeff Jarvis in a 2009 book calling for them to be digitised. “I recant,” he wrote in the Atlantic nearly 15 years later, in 2023.

Some readers like a print book’s sensory qualities: its feel and smell. For others, there is satisfaction in assembling a book collection. Like vinyl records, sales of which are also healthy, print books can be collected as valued objects to be cherished.

Books signify reverence for culture – and bring it into domestic, accessible spaces. Print books in particular are carriers of history, knowledge and shared stories – as I’m learning through an ongoing joint research project into community publishing in regional Australia. And widespread horror at the destruction of books and libraries in Ukraine and Gaza reflects our collective knowledge that they represent culture itself.

With Alexandra Dane, Sandra Phillips and Kim Wilkins, I interviewed 27 self-published authors. Most of them wanted to create a physical book, rather than an ebook.

Our research showed people instinctively turned to the print format as the best way to preserve their memories and histories, and share these with other people in their communities.

Sonya Bradley-Shoyer from Burdekin, north Queensland, self-published her poetry collection Come … Walk With Me in 2024 as a print book with multiple photographs and illustrations.

“People would say, Sonya, you really need to put them in a book so you have them there for future,” she reflected. It took her “a number of years” to produce her book.

Print allows books to circulate visibly in a community. Another author we interviewed, Christine Adams, has written a number of books relating to the history of Broken Hill, and her books have been sold at local venues including the Broken Hill fire station and the tourist information centre. Adams sees her books as preserving cultural heritage and local stories, telling us what she does is “all for a love of the city.”

George Venables, a Burdekin-based author, spoke to us about publishing an anthology with his local writers’ group.

Making a print book is meaningful for young writers. Jane Vaughan is a bookseller at Big Sky Stories in Broken Hill, where she ran a series of workshops for young people culminating in the publication of an anthology of stories. Jane spoke to us about how meaningful the book launch was “when they had that book, and they were walking around going, this is mine, this is mine. Mine’s on this page.”

That value, of a book being shared in a community, also came through in our conversation with Olivia Nigro from Running Water Community Press, an author-run publisher in Alice Springs focusing on First Nations storytelling and copyright justice. Olivia told us about the Arelhekenhe Angkentye: Women’s Talk poetry collection, which they published in 2020.

“Having it as a tangible paperback format, for people to hold and read and carry with them where they go is really important.”

The physical objects of books are meaningful; so, too, is their loss. Last year, I found myself standing next to The Empty Library. This monument in the Bebelplatz square in Berlin is simple, but powerful.

It’s a square of glass set into the ground. Below is a white void filled with empty bookshelves. The monument commemorates the Nazi book burnings, in which crowds of people watched the destruction of 20,000 blacklisted books.

Because books hold culture, history, language, knowledge and stories, their deliberate destruction has a deep impact. In an opinion piece for the LA Times, cultural heritage researcher Laila Hussein Moustafa writes that “the destruction of libraries in times of war and violent conflict is tragically common”. She noted the attack by Bosnian Serb forces on the National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992, and the looting of the Baghdad National Library in 2003.

What is at stake in such destruction, Moustafa writes, is libraries as “cultural repositories. They hold collective memory, preserve cultural heritage, showcase societal development and afford individuals the opportunity for learning and growth.”

This year, reporting on the destruction of Gaza’s libraries by the Israeli Defence Force, journalist Shahd Alnaami wrote that seeing images of books burning “felt like fire burning my own heart.” She continued:

“The attacks on Gaza’s libraries are targeting not just the buildings themselves, but the very essence of what Gaza represents. They are part of the effort to erase our history and prevent future generations from becoming educated and aware of their own identity.”

Part of the “heartbreaking reality” of the scale of the attacks on Gaza, Alnaami wrote, is that some of the surviving books have had to be burned by Palestinians for fuel. Novelist and academic Yousri al-Ghoul writes that on a day-to-day level, the tragic loss of culture is subsumed because “survival itself hangs in the balance.”

In May 2024, a Russian missile hit Ukraine’s largest printing house, killing seven people and injuring 21. The strike also destroyed 50,000 newly published books. It took place just a week before the Arsenal book festival, a popular event in Kiev where many of the destroyed books were due to be sold. Burnt copies of the books were displayed among the new releases on show.

Print books can communicate something about who we are.

Print books may be burnt or absent. They may be shared in a community, held in a library, cherished in a home or shared online. In all these contexts, print books are vivid objects, reminders of culture’s precarity and its endurance.

Beth Driscoll is Associate Professor in Publishing and Communications, The University of Melbourne

This is an abridged version of an article republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

![]()