Releases from Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Maggie Nicols/Robert Mitchell/Alya Al Sultani, and Gordon Beck Trio and Quintet

DAVID RENTON recommends a books that explores the ways in which disabled people are made to feel both of and not part of this world

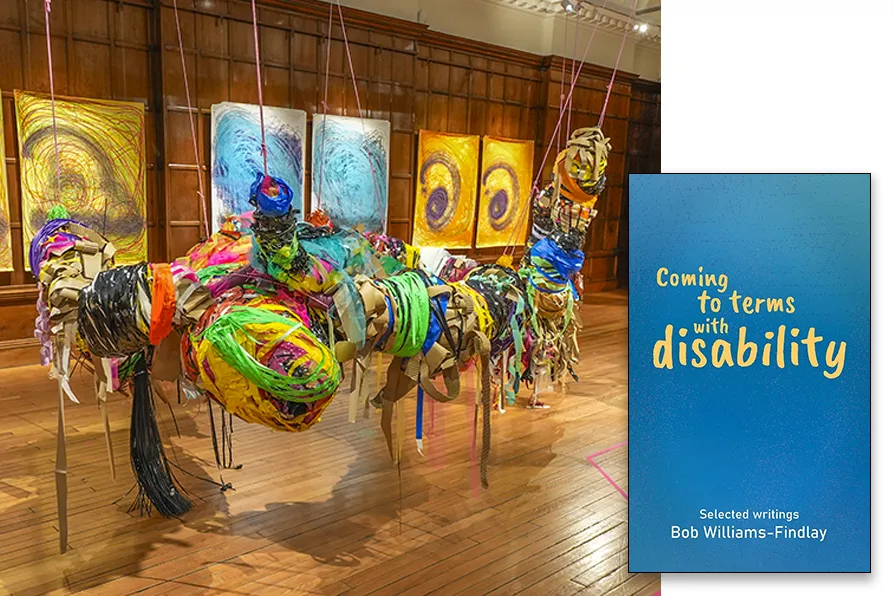

IS THIS A PARADOX? Work by Turner Prize winner 2025 Nnena Kalu, who is autistic with “limited verbal communication” at Cartwright Hall Art Gallery in Bradford

IS THIS A PARADOX? Work by Turner Prize winner 2025 Nnena Kalu, who is autistic with “limited verbal communication” at Cartwright Hall Art Gallery in Bradford

Coming to Terms with Disability

Bob Williams-Findlay, Resistance Books, £8

FOR many decades, Bob Williams-Findlay has been a leading activist within disabled people’s movements.

Last year, Pluto published his book Disability Praxis, a work of sophisticated political theory. That work defended what activists call “the social model” of disability, the insistence, in other words, in seeing the harm to disabled people’s lives as being caused by the unjust allocation of resources within society.

The most familiar example of that model is the following. If you want to understand why people with mobility impairments have difficulty in using the London Underground, the essential cause is not a physical weakness of their legs, but the fact that 179 out of 272 underground stations require those walking from the station entrance to the platform to use stairs, offering people with common mobility impairments no chance of using those stations.

Disability Praxis was a treasure-trove of activist experience and politically engaged theory. It addressed difficult questions. The model implies that beneath the social relations which prevent disabled people from having equal access to education and employment, and beneath the discriminatory stories which are told about disabled people, there is a deeper reality of impairment – but is that reality to any extent socially constructed? Is its reality subjective (ie known best by the disabled person) or objective?

Coming to Terms with Disability is, at just 95 pages, a much narrower book. The first chapter explores the representation of disabled people in culture, starting with the example of the Tardis in Doctor Who acquiring its own ramp. Disability counter-culture is waning, Williams-Findlay, argues. He is troubled both by its weakness and by people’s need for it.

He explores the ways in which disabled people are made to feel both of and not part of this world. He describes how disabled people can internalise oppressive views of their own bodies. Disabled people’s art is paradoxical, he insists, and made more so by people’s conflation of impairment reality and disability, by the depoliticisation of disabled communities, and by attempts to “celebrate disability.”

A second chapter explores some contradictions of spectating abled-body sport. Williams-Findlay first watched a live football match in 1962 and acknowledges the poetry of the game, alongside its commercialisation.

The third chapter reflects on the decision of one campaign, Act4Inclusion, at its 2001 AGM to adopt eco-social politics, recognising that disabled people who have the least resources to adapt to environmental change are likely to be more vulnerable to extreme climate events and have little to gain from a world in which climate change compels movement across borders.

Another theme of his work is that so much remains to be understood. Williams-Findlay ends his first chapter with a question. “When a person with cerebral palsy, for example, paints a vase of flowers; is this no different to someone without an impairment undertaking the painting?” Any satisfying answer, the author suggests, will itself be a paradox.

The author who emerges from the pages of this book is principled, committed, full of insights, and keen to grasp the relationships between different kinds of struggle.