STEPHANIE DENNISON and ALFREDO LUIZ DE OLIVEIRA SUPPIA explain the political context of The Secret Agent, a gripping thriller that reminds us why academic freedom needs protecting

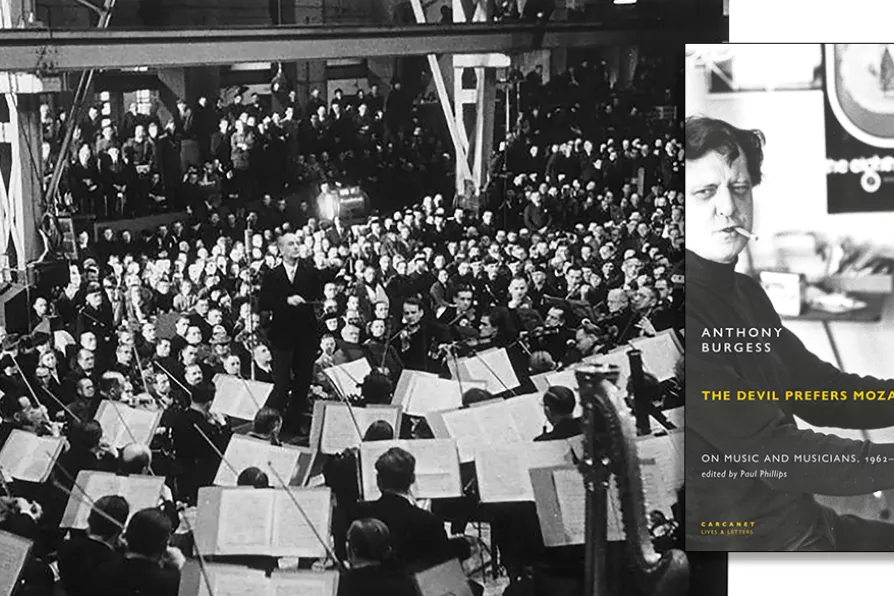

NAZI ASPIRATIONS: Wilhelm Furtwangler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in a "work-break" concert at AEG in February 1941, organized by the Nazi Strength Through Joy program

[Bundesarchiv/CC]

NAZI ASPIRATIONS: Wilhelm Furtwangler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in a "work-break" concert at AEG in February 1941, organized by the Nazi Strength Through Joy program

[Bundesarchiv/CC]

The Devil Prefers Mozart: On Music and Musicians, 1962-1993

Anthony Burgess, Carcanet, £30

IN old age, one of violinist Yehudi Menuhin’s mottos was: “My life has been spent in building utopias.” Author, musician and critic Anthony Burgess might be said to have done the opposite, given that his most well-known creation is a work of dystopian fiction. Yet Burgess later disavowed A Clockwork Orange, and wanted to be seen instead as a serious composer.

In The Devil Prefers Mozart, a fascinating collection of the author’s musical writings, brilliantly edited and contextualised by Paul Phillips, Burgess often seems to aspire to Menuhin’s utopian condition. In a review of the violinist’s autobiography, for example, he cites Menuhin’s life motto approvingly, and declares in response: “In Britain’s present cacotopia may he continue to rule an enclave of virtue and beauty.”

As many people have pointed out, though, the problem with utopias is that they are subjective: one person’s utopia is another’s dystopia; and sometimes, utopia and cacotopia might even co-exist within the same person’s vision.

MARJORIE MAYO welcomes an account of family life after Oscar Wilde, a cathartic exercise, written by his grandson

JONATHAN TAYLOR appreciates how, for a black British musician, to walk onstage can be a rebellious act

JONATHAN TAYLOR attempts to disentangle the mind, self and political opinions of a successful bourgeois novelist

JONATHAN TAYLOR is intrigued by an account of the struggle of Soviet-era musicians to adapt to the strictures of social realism