GEOFF BOTTOMS applauds a version set amid the violent conflicts of the 19th century west African Oyo empire before the intervention of British colonialism

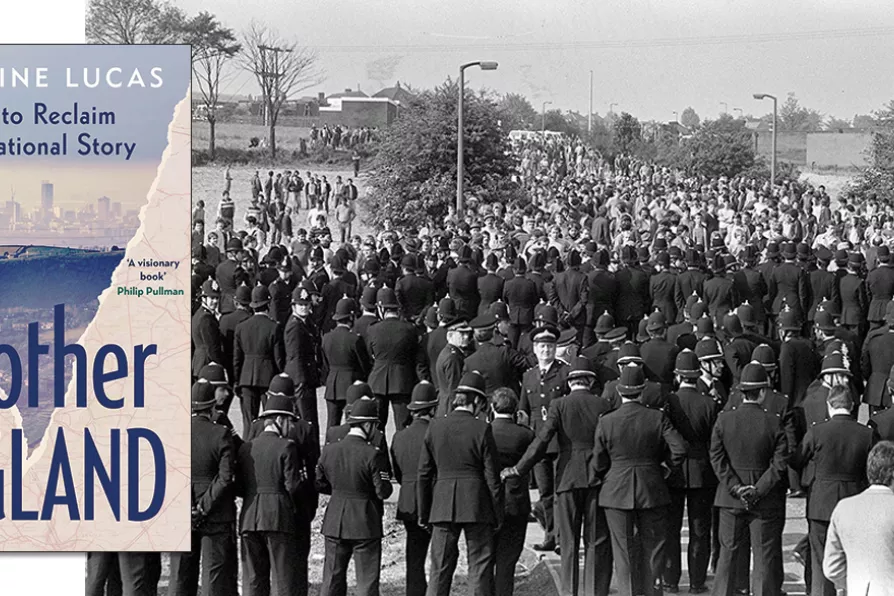

WHOSE SIDE ARE YOU ON?: Intimidating police presence, hellbent on confrontation, on the hill heading to the Orgreave Coking Plant near Rotherham, May 31 1984

WHOSE SIDE ARE YOU ON?: Intimidating police presence, hellbent on confrontation, on the hill heading to the Orgreave Coking Plant near Rotherham, May 31 1984

Another England: How to Reclaim Our National Story

Caroline Lucas, Penguin, £10.99

THE dustjacket promises much: a new look at “Englishness” through England’s literature and its hidden history of popular struggle.

Yet the book starts with two dubious assumptions. Firstly, Caroline Lucas tells us that we need to reclaim the notion of “Englishness” from “the cheerleaders for Brexit,” that is, that the Brexit vote was an expression of “imperialist nostalgia.” Such might be an attitude she encountered in the Commons bars and tearoom but, as Lucas herself later states, when she decided to visit Brexit-voting areas and listen to ordinary people she found that their vote was a protest against loss of economic security and the sense of political powerlessness.

The second assumption is Lucas’s claim that the “left ... have failed to offer their own, alternative vision of what Englishness means.” Again while the “progressives” of Caroline’s social circle might be ignorant of alternative histories it is certainly not true of the communists and radical socialists of the first 50 to 70 years of the 20th century. Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton, AL Morton, Eric Hobsbawm, the Hammonds, GDH Cole and EP Thompson were all engaged in the process of establishing and explaining the history of radical and working-class movements and struggles.

MARJORIE MAYO recommends a disturbing book that seeks to recover traces of the past that have been erased by Israeli colonialism

RON JACOBS welcomes the translation into English of an angry cry from the place they call the periphery