New releases from Kassi Valazza, Mark Pritchard & Thom Yorke, and Friendship

POSSESSED: John Coltrane

POSSESSED: John Coltrane

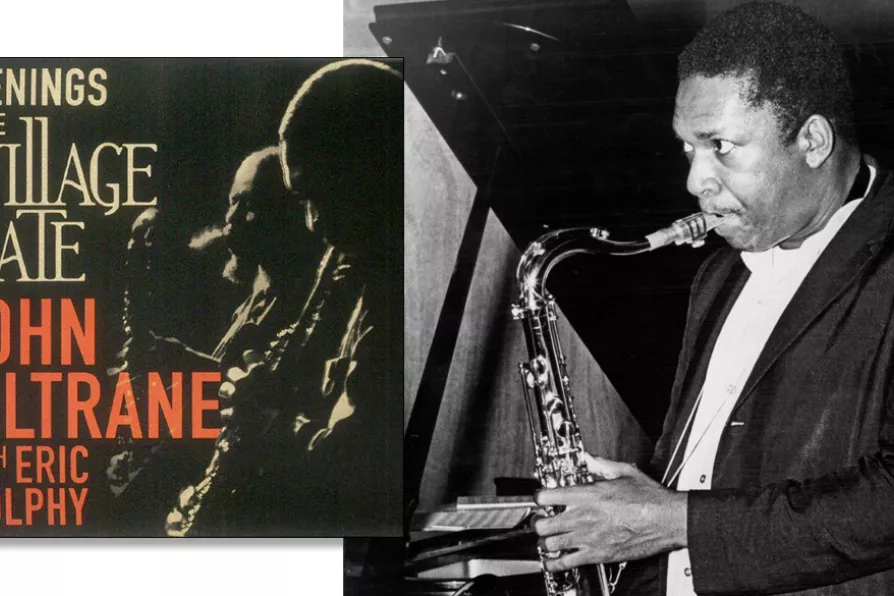

LIKE no other people before us, we live with the songs of the dead. These captured incantations of the vanished can be heard at their uncanniest in Evenings at the Village: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy.

On this strange, urgent, exploratory, chaotic-ecstatic album the musicians and their music appear both distant and close, manic and meditative, full of physical force yet strangely disembodied, heard in a deafening whispering that is both frustratingly indistinct and searingly truthful, searching and unsatisfied.

This mythic live recording is an odd artifact of random tests on the then-new sound system of the famed Greenwich Village club at Thompson and Bleecker.

Made in the sweltering summer of 1961, the tapes were lost, then found — then lost and found again, finally in the sound archives of the New York Public Library.

The material has now been issued for the first time on Impulse!

Coltrane recorded his first studio album for Impulse! in the spring of 1961. Africa/Brass is a conclave of symphonic set-pieces and shouts spurring on the saxophonist’s solos. The project embraced experiment as a way of musical being and of being musical.

Africa/Brass was issued the very month that Coltrane and his still-evolving band began their late-summer run at the Village Gate. The venue offered longer bookings for its acts than did its competitors like the Village Vanguard. At the Gate, the residencies extended to three or four weeks and encouraged growth and exploration.

After careening through the exacting harmonic obstacle course of Giant Steps and then treating the Broadway hit My Favorite Things with a modicum of marketable decorum, the Village Gate live recording relentlessly courts chaos. This is a voyage of discovery to a New World on the far side of the Atlantic.

The quartet Coltrane had called to his banner counted Elvin Jones on drums, McCoy Tyner on piano, and Reggie Workman on bass.

Joining the Village Gate ranks was Coltrane’s slightly younger contemporary Eric Dolphy. The two had known each other a few years before in Los Angeles and they renewed their friendship when Dolphy moved to New York in 1959.

The opening track on the album had to be My Favorite Things — and so it is.

The Village Gate soundman seems to have pressed the record button midway through the proceedings. The order of the solos was not fixed in the group and McCoy Tyner is heard here only accompanying.

Presumably he introduced the tune with the trio, his opening now as gone as the cigarette smoke that filled the place as he played.

This Village Gate version clocks in at a scant 15 minutes. In the coming years, Coltrane would extend the tune to as long as an hour.

When the tape starts running we hear Jones pushing the waltz ahead. It is he who provides the core energy, cogenerated with Tyner and Workman.

The mic is placed right up against the drummer, his incessantly inventive left hand at the snare and left foot at the hi-hat set the scrim through which we hear everything else—the layers now overlapping, now rupturing.

Beyond this aural border, Workman and Tyner add their distinct yet collaborative voices. More distant still the flute of Dolphy’s dances dervishly.

It whirls, whistles, nestles in cracks, and bursts upward to flutter and kite in the waltzing wind.

The familiar showtune surfaces above the swells and then Coltrane takes it up. His soprano saxophone trills and eddies, races along and against the currents that he generates but that he can’t — won’t — control and that take him where they will.

Consistency of style and intent is too often taken as an aesthetic goal, a hallmark of Great Art.

This album shouts otherwise. The epic vamp broken by bursts of harmonic action in My Favorite Things is followed by the more familiar motive syntax of When Lights Are Low by jazz father, Benny Carter, who, along with his alto saxophone colleague Johnny Hodges exerted a profound influence on Coltrane.

Now on bass clarinet, Dolphy introduces the tune while Tyner sits out (“strolls” as the beboppers would have put it) for the first few minutes in order to give the soloist space to test the limits of that syntax.

Once Tyner enters and begins providing a chordal framework, Dolphy goes ever farther off-piste — or maybe out-of-pulpit — with an oration of effect and feeling a vast distance from the nuanced song stylings of Carter and Hodges.

Coltrane’s soprano saxophone follows with furious filigree ever more fantastical, even fanatical — possessed, aflame. When the bandleader flickers out, Tyner is heard as a soloist for the first time on the album.

He is as fast as the reed players before him, but precise (as perhaps a piano must be), his improvisation anchoring, almost retrospective.

From here it is back to the extended vamping, this time on two adjacent minor chords in Impressions. The pace has quickened.

Already uncontainable, the energy finds new fuel, and burns brighter now. The speed forces Coltrane to become more focused in a fiery echo of his work on the same chord changes a few years earlier with Miles Davis on So What.

These way-out orations quest after an undefined universal. It is a mission fascinated by folk tunes, by the modes and scales of world music that in turn lead to other worlds.

Coltrane steers his group back to Olde England for a Greensleeves, another waltz that is the Anglophone cousin of the ersatz Austrians of My Favorite Things. If you’re expecting a seasonal jingle as Christmas nears, look and listen elsewhere. This is not a music of easy good cheer and spiced cocktails.

The last destination of this journey of August 1961 is back to Africa, a trip inspired by the old notion that to travel across space is also to travel back in time. Just as important is the belief that North and South share a common music and humanity. To listen to this Village Gate programme is to listen to Coltrane and Company search for that connection.

In this traversal of history and geography there is brimstone and brotherhood. Time is upended. The past sounds like the future, the future like the past. Fraternity can be frightening.

Dolphy would be dead three years later at the age of 35. Cancer claimed Coltrane in 1967.

What do we hear in those reanimated jazz voices from 1961 and what messages do they sing to us today? That the quest for simplicity is as complicated now as it was six decades ago; that frenzied futility can be both ugly and beautiful, inspiring and unknowable, exhilarating and threatening; that the ghosts are still crying, cajoling, extolling, banging at the gate.

This is an abridged version of an article that first appeared in Counterpunch.

David Yearsley’s latest book is Sex, Death, and Minuets: Anna Magdalena Bach and Her Musical Notebooks. He can be reached at dgyearsley@gmail.com.