SIMON PARSONS applauds an artist who rescues and rehumanises stories of women, the victims of violence, from a feminist perspective

RICHARD MURGATROYD appreciates a study that urges us to think about water differently, as a living entity with its own logic and intelligence

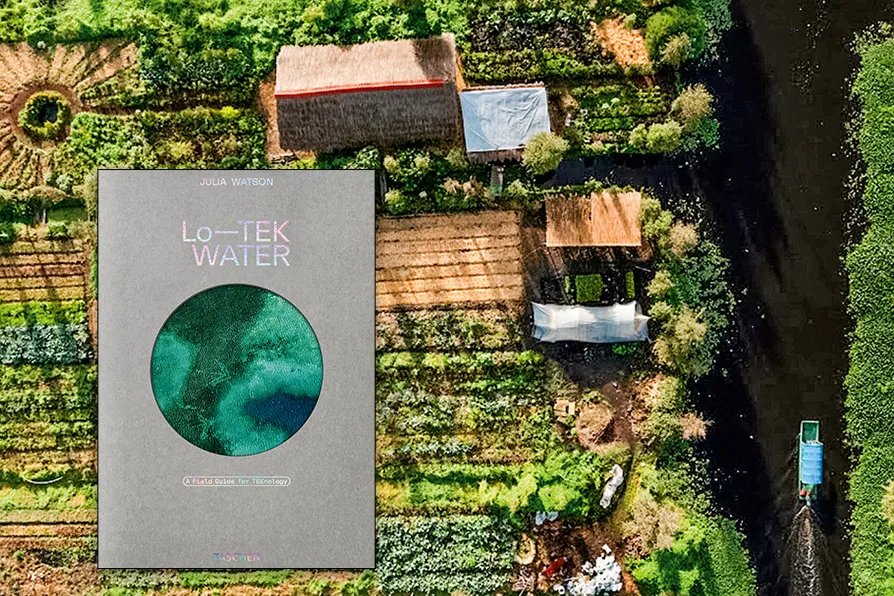

SUSTAINABLE: Chinampa Islands of the Nahua Xochimilca, Mexico. Classified as vulnerable to climate change, the expansion of the chinampa technology critically improveS the habitability of the Valley of Mexico lakes ecosystem. [Pic: George Steinmetz]

SUSTAINABLE: Chinampa Islands of the Nahua Xochimilca, Mexico. Classified as vulnerable to climate change, the expansion of the chinampa technology critically improveS the habitability of the Valley of Mexico lakes ecosystem. [Pic: George Steinmetz]

Lo-TEK Water: A Field Guide for TEKnology

Julia Watson, Taschen, £50

WATER makes human society possible. Without it we would have no agriculture, modern cities, energy, mass production and so much more.

Yet it has become just another industrial commodity to be bought and sold for profit.

In the UK today the key focus is now on privatisation and polls show two thirds of people now demand a return to common ownership. Bubbling away beneath the surface are terrible water-based threats to climate, public health, biodiversity and food.

This new book by Julia Watson on water encourages us to look backwards to move forwards.

Watson is a champion of “Lo-TEKnology,” which seeks to apply “Traditional Ecological Knowledge” to address the social and environmental crises of our age. While TEK has wide applications, the focus here on water is particularly urgent. It’s starting place is far removed from the short-term, extractive, industrial capitalist approach and reaches for the wisdom developed by our human ancestors throughout the world for millennia.

We are urged to think about water differently, as a living entity with its own logic and intelligence. Not only is water a “life-force” in its own right, but through its “symbiotic relationships” with all aspects of the natural world, it underpins and shapes that nature. This is not a static process. Water is always in motion, an essential part of the cyclical seasons and the planet’s natural movements and periods of renewal over time.

In this field guide Watson illustrates the point by exploring over 40 mini-case studies where humans have successfully created systems that co-exist with water. They are divided not through human categories, but water’s own: salty, brackish and fresh.

This Lo-TEK approach is anti-colonial. It requires us to listen respectfully to the ancestral knowledge of indigenous peoples. Their voices and interests are centre stage.

Each case study is co-authored by local people who provide plenty of insights, authenticity and honesty about the problems their communities face, as well as the opportunities. Interestingly, while each case study is of course specific in place and time, a pattern begins to form around shared principles.

Take the case of the Sundanese people of Java, Indonesia. Their terracing systems go back 2000 years based on the philosophy of alam jeung, jaman kawulaan, saur elingkeun, which translates: “To keep up with changing times, while still holding to what was given by the ancestors, to sort out what is allowed and what is not.”

The Sundanese terraces embody these principles by skilfully managing water flow to provide food in the form of mixed agriculture and fish, prevent soil erosion, and clean up human waste. They also have great potential for generating clean hydro-power. The key here is that the community has developed a sustainable system that works with the actual natural properties of their water.

So too do the floating islands of the Bhumihin Krishok people of southern Bangladesh. Faced with a serious land shortage in an area under water for eight months a year, the local people faced a challenging environment even before European colonists introduced a very invasive species of water hyacinth into the wetlands in the 19th century.

However, the Bhumihin Krishok responded by building – literally – on ancient agricultural systems. The water hyacinth was naturally very buoyant. They use mats of the stuff to form the base of incredibly productive floating vegetable gardens, capable of multiple harvests. In the dry season the remains of the beds are used to fertilise the winter harvest. So, its all about understanding the natural rhythms of the water and using the plants it sustains in a sustainable cycle.

The Chinampa Islands of the Nahua Xochimilca people in Mexico are more permanent, but still cut with the grain of the local land and water resources. Here a network of canals irrigate artificial island fields and are fed by fertiliser taken from sediment from the bottom.

The plants, fish and micro-organisms in the water also help cleanse waste from nearby Mexico City, a vast industrial conurbation. The fields themselves can produce up to eight crops a year and are richly biodiverse. The chinampa system dates back to the Aztecs and offers a great potential model for other urban areas, especially as global warming will lead to a much wetter climate.

Many more case studies are explored, all of which are both inspiring and exciting. We are left with a sense of wonder at the sheer ingenuity of our species. If nothing else, they reveal our capacity to develop systems that are in harmony with the flow of water and the wider natural circumstances.

But the circumstances of late capitalism are not natural. Time and again, the authors explain the very real threats to the systems they describe.

Key problems are a movement of young people away to cities due to rural poverty, commercialisation of resources, rising and unpredictable water movements due to climate change and pollution. Together, these are steadily undermining the basis of many of these ancient systems and the communities that developed them.

Behind it all lies a bigger question: what is real value?

In a globalised capitalist world value is measured by profit. In the natural world that means little. We ignore that reality at our peril. As Watson points out: “Water has always carried warnings. It does not die alone; when it is poisoned, obstructed or exploited it takes entire eco-systems and communities with it.”

Will we listen? If we do, how must we change? The author provides some hopeful examples of contemporary Lo-TEK water projects from around the world, but they are mainly small-scale and woefully short of investment. It seems only a democratic, planned, publicly owned economy is likely to rise to the challenge.

So, this is a book that deserves to be read. I can honestly say that I found it hard to put down. It is also sumptuously illustrated, with beautiful photographs and well-drawn diagrams that explain very clearly how everything works. Its that mixture of practical potential, rooted in principle, that gives hope.