JENNY MITCHELL, poetry co-editor for the Morning Star, introduces her priorities, and her first selection

Jimmy watches Countdown and tries to ignore his bills, grief, COPD and frailty. Meanwhile, his carer walks a tightrope between kindness and reality

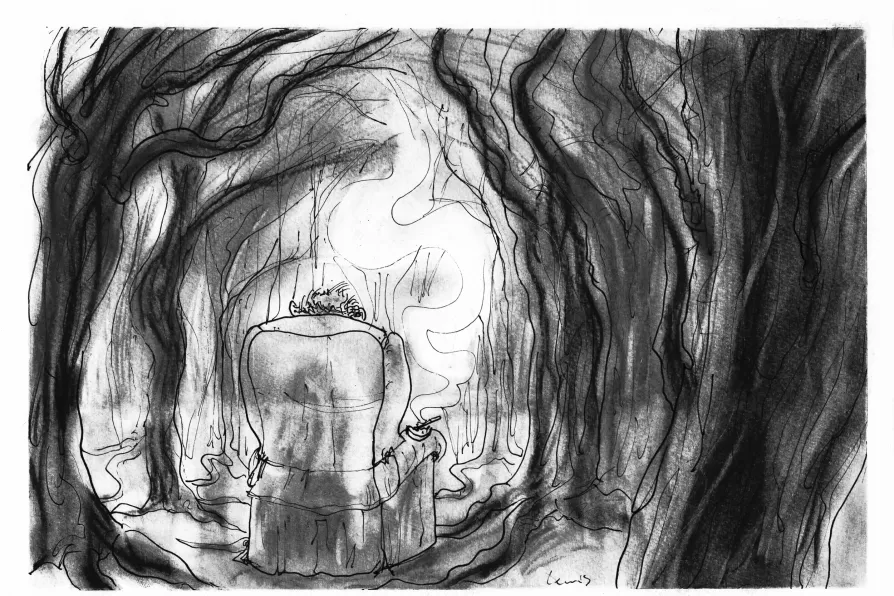

Illustration by Lewis Marsden

Illustration by Lewis Marsden

IT was after the accident, he said. The accident and the layoff, or was it the layoff first. It didn’t matter, sure, it all happened around the same time anyway, he said. He looked me in the eye as I washed him, a look that was casual, like we were in a bar, just having a few pints. I felt like saying don’t look at me, but it would have sounded odd. He talked football as I dried him, how it wasn’t like that years ago, how years ago you, you’d get broke up. I emptied another plastic basin down the sink, we kept talking football. There wasn’t any real hair of note on his head, but he insisted on Brylcreem anyway, and after the Brylcreem a bit of old spice. He didn’t like under arm deodorant, said it was for Marie Annes, so I gave him talc instead. He was heavy to lift but I was used to it now. He talked about his motorbike in the drive, an auld Triumph covered with a green tarp, now weighed down with leaves and litter blown in from the street.

A grand yoke, he said.

Ah yeah, a grand yoke, I said.

I’ll be back out on her again soon, as soon as I get better.

Of course you will, I said.

I reminded him about his teeth, he brushes them quick, so quick that he may as well not have bothered. It was amazing how he still had them. I’m sweating after finally getting his trousers and shirt on, an old Manchester United top from what looked like the ’90s. We’ll need to get you some new clothes next week, I said, as a pink toe peered out from a discoloured white sock.

Sure, I’m grand, he said.

We’ll sort something out anyway, I said.

I found his glasses and his hearing aid. Countdown was starting soon, he said. He lit a smoke.

It hasn’t been the same since he died, he said.

Who’s that?

Richard Whiteley, he said.

The blonde woman that took out the consonants and vowels was hypnotic; I could hear Jimmy talking in the distance but forgot where I was for a moment.

You like her, he said. He laughed and smiled a mouthful of yellow teeth, then blew smoke in the air. I coughed and told him he needed to cut down.

Remember what the doctor said about your COPD, I said.

When I start listening to doctors, that’s when I’ll really start worrying, pal.

He palmed around looking for something. He’d got faded tattoos on his forearms, one of a Celtic cross, the other a faded flower with, possibly, Jean underneath, but I couldn’t tell. The hearing aid made an awful screech as he eventually got to grips with putting it on, then carefully taking his glasses from the case, placing them on slowly, then closing the case with a loud clunk, like a ritual. Sometimes he looked like a different person when he took his glasses off, as if something had drained from him.

A picture lay on the mantlepiece of his late wife. She was pretty, and even from the black and white photo looked as if she had brown eyes. I suppose you could never tell though.

I looked at him, and a proud man with glasses and a shiny head looked back.

Beautiful isn’t she.

She is, I said. What colour were her eyes?

Brown.

I thought so, I said.

Paula kept texting me, said she’d be on her way.

You never stop looking at that phone, he said. It’s all phones nowadays, sure Jaysus I don’t know what you do be looking at. Is it blue movies or something?

It’s not that Joe, I said. I’m just texting me girlfriend.

What’s she like?

She’s alright, I laughed. I like her anyway.

I take out my phone and show him a photo of her. His hands are shovel-like, the phone looks different in his palm, like it’s suddenly shrunk.

She’s gorgeous, he said, for feck’s sake what’s she doing with you?

I laugh and take back the phone. It looked normal again. Countdown was on Maths now. He took out a small notepad and bookie’s pen and began totting up the required target. He was worse than me with numbers, but it didn’t seem to bother him.

Will you have a cup of tea and a biscuit, I asked.

I will, he said.

The kettle made hard work of the water, it made me nervous, like it could explode any minute. But Jimmy never seemed to notice.

The letters beside the microwave were unopened. They were neatly stacked. Some envelopes were brown, others white. I started from the top. One was from an internet provider trying to sell cheap Wifi. Unfortunately for them, Jimmy couldn’t send a text let alone google. Another was an electricity bill, where are they getting that bill from, all he does is watch TV and put on the sitting room lamp, he gets meals on wheels most days, so I barely use the cooker. I grind my teeth, I’ll call them in the morning. Not that it’ll do me any good.

The next letter was from the hospital, the respiratory section. I looked back through the hall, catching a glimpse of him, head down on his notepad, smoke dangling from one side of his mouth. The letter didn’t seem serious at first, until you read between the lines. As soon as possible was said, more than once. Words like pulmonary, clouding, growths and incomplete remission. It was getting late now, too late to sort appointments, too late to talk to him about it, too far into the evening to worry him.

I decided to finish making the tea and tell him in the morning. I lay the tea on the table beside him.

Where’s me biscuits, he said.

I come back with the biscuits, lay them on the table. I sit down across from the mantlepiece. A young good-looking woman with brown eyes in a black and white photo looked back at me. Paula texted me again, said she was on her way, I told her I might be a few minutes late. They eventually gave the total. Jimmy was fourteen short. I wipe down the tables, sweep and mop the floors in the hall, kitchen and sitting room, in between spurts of vowel and consonant please. He lights another cigarette: the smell, it gets into everything, it gets into the curtains, the walls, the furniture, your clothes. One day I changed the glass shade of the sitting room light. It was sticky, yellow, stained with nicotine. The white of the walls looks a bit dull and yellowy come to think of it, I can’t imagine why.

Sometimes he blew circles, perfectly round circles, that rose slowly toward the ceiling until they finally disappeared. He lifted a biscuit to his lips with his thumb and two nicotine-stained fingers.

Are you meeting your girlfriend tonight?

I am.

Did you ever think of marrying her?

I didn’t reply. He took a sup of tea, sipped it like soup, it annoyed me sometimes.

Eventually he switched on Antiques Roadshow.

Now look at these two auld ones, now who’d buy that crap.

There were two elderly women talking to the presenter. On the table between them was a Victorian backgammon set. It was left to me by my great uncle, one of the women said. We’ve valued it at six hundred pound, said the presenter.

Jimmy laughed. Six hundred pound for that, I’d throw that in the bin if someone gave me it. Are people stupid or what?

He takes the control, switches off the TV.

He takes a drag, then a sip of now lukewarm tea.

When Jean died, I thought I’d never get right, I hit the drink, I worked but I was never really there. It was like I went to work in someone else’s body, and when I came home I drank, it took the edge away. Years went past like that. I thought I’d never get right but I did eventually. When the grandkids were born and that.

My phone beeped a text. I didn’t bother looking at it.

I suppose what I’m trying to say is you just keep moving forward, either way, no matter what happens, he said.

I nodded, then finally looked at the new text.

It was from Paula. OK, she said. XX.

I done a last bit of cleaning, made sure I left nothing on. I wiped the counter down in the kitchen, I took the bin out, a familiar smell wafted from it. The cold air hits me as I take it outside. I get back in, flushed.

Everything OK Jimmy? I’m going to head off now in a few minutes. Is there anything else you need? I could see he’d been crying. Are you alright Jimmy? I asked.

I’m grand, he said.

Are you sure? Do you need anything else before I go?

No, I’m grand.

I need to talk to you in the morning. About a few appointments.

OK, he said.

The phone beeped again, I took my coat and keys. I walked around one last time, making sure I knocked everything off.

I’m heading off now Jimmy. You sure you don’t need anything else.

I’m grand, he said.

I nodded OK, even though I knew he wasn’t.

I shut the door behind me, slowly until I heard it click.

Declan Geraghty is a working-class writer and poet from Dublin. He has work published with Epoque Press, Culture Matters UK and DoubleSpeak Magazine.

Stories, of up to 1,600 words, should be submitted to: Morningstarshortstories@gmail.com