JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

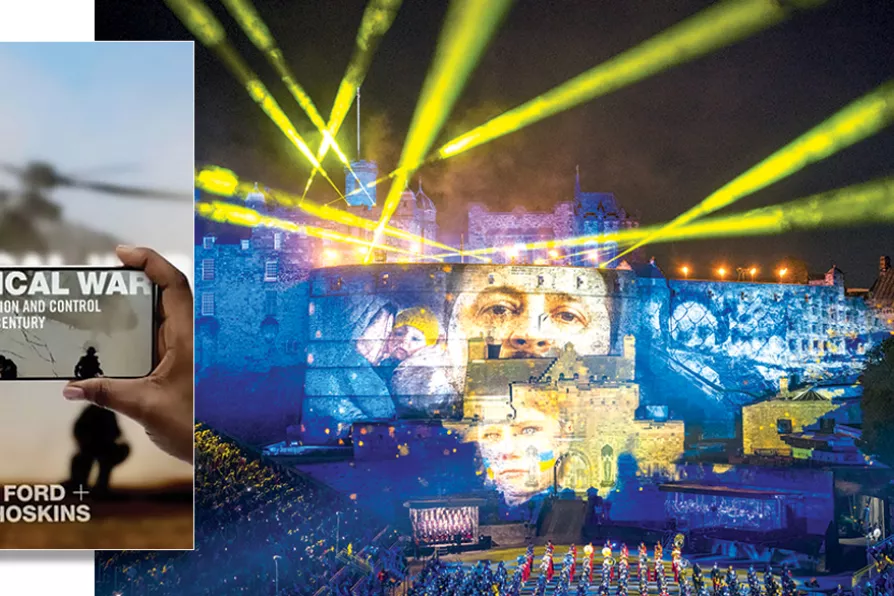

RELENTLESS VISUAL ASSAULT: An image of Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelenskyy is projected onto Edinburgh Castle during the finale at this year's Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo

RELENTLESS VISUAL ASSAULT: An image of Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelenskyy is projected onto Edinburgh Castle during the finale at this year's Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo

Radical War: Data, Attention and Control in the 21st Century

Matthew Ford and Andrew Hoskins

Hurst £20

THERE is no doubt that digital technology with all its open-ended potential is changing war — but less acknowledgement that it is changing the meaning of war.

That matters, because wars as classically understood were prosecuted with purpose, never in a vacuum, by tradition-bound military institutions of nation-states, reinforced by mass-media sappers to ensure public legitimacy around an assembled consensus.

The smartphone, however, has changed everything. Mass connectivity, led not by states but corporations leveraging globalisation, is creating combatants of us all, at least in terms of how wars are understood and represented, and leaving the military behind.

This is the underlying argument of Radical War, a complex and at times dense set of reflections on the undeniably disturbing interactions between technological change and political violence.

GAVIN O’TOOLE welcomes, and recommends a a candid, evidence-based record of Britain’s role in the slaughter visited by Israel upon the Palestinians

![SHAMELESS DISPLAY OF COERCION: Previously unreleased photos of Guantanamo captives, 2002, brought to Guantanamo Bay from Afghanistan by way of Incirlik, Turkey. [Pic: Staff Sergeant Jeremy Lock/CC]]( https://msd11.gn.apc.org/sites/default/files/styles/low_resolution/public/2025-11/cia%20web2.jpg.webp?itok=SyFt0Pzt)

GUILLERMO THOMAS enjoys a survey of the current state of the CIA (aka Langley) from an expert and insider of sorts

As six out of 10 Argentines don’t vote for Milei LEONEL POBLETE CODUTTI looks at the country’s real crisis that runs far deeper than just the ballot box

GORDON PARSONS steps warily through the pessimistic world view of an influential US conservative