Climate activist and writer JANE ROGERS introduces her new collection, Fire-ready, and examines the connection between life and fiction

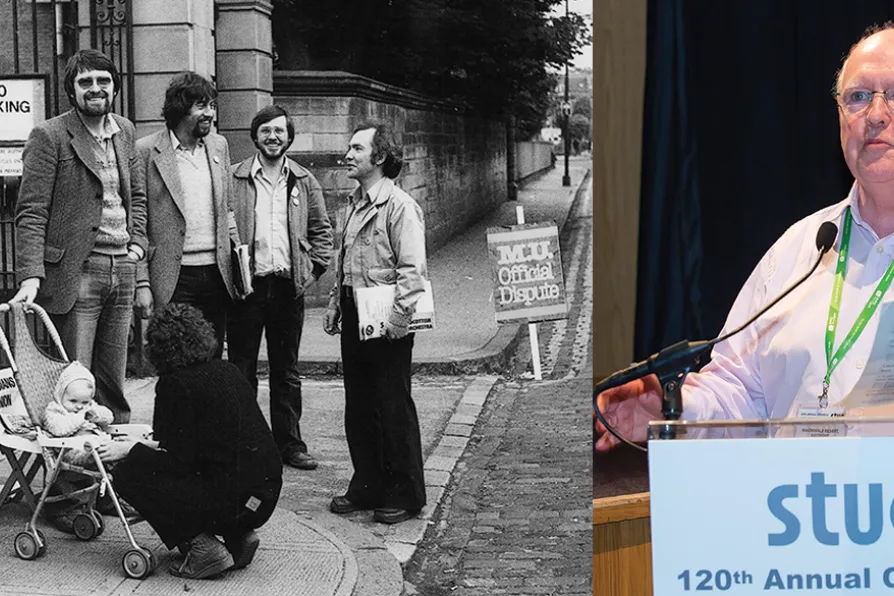

ON SONG: (L to R) On the picket line with fellow composers 1980, a strike to save the Scottish Symphony Orchestra (SSO); Eddie McGuire addresses the STUC

[edwardmcguire.com]

ON SONG: (L to R) On the picket line with fellow composers 1980, a strike to save the Scottish Symphony Orchestra (SSO); Eddie McGuire addresses the STUC

[edwardmcguire.com]

YOU can learn a lot about a composer, and a person, simply from the place you first meet them. My first encounter with Eddie McGuire was at a meeting of Radical Options for Scotland and Europe in the Unite offices in Glasgow. Since then, to this day, most of my encounters with the composer have been at a protest or rally rather than in a concert hall.

Shortly after I moved to Scotland, after my years living in Vilnius, I attended a Morning Star event (although I can’t remember for the life of me which) where Keith Stoddart deployed his usual charm and curiosity and quickly discovered I was a composer. His instant response was: “In Scotland you only need to know two composers James MacMillan and Eddie McGuire.”

Two very telling signs about a composer who celebrates his 75th this year.

April 9 1928 – July 26 2025

ANGUS REID recommends a visit to an outstanding gathering of national and international folk musicians in the northern archipelago