JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

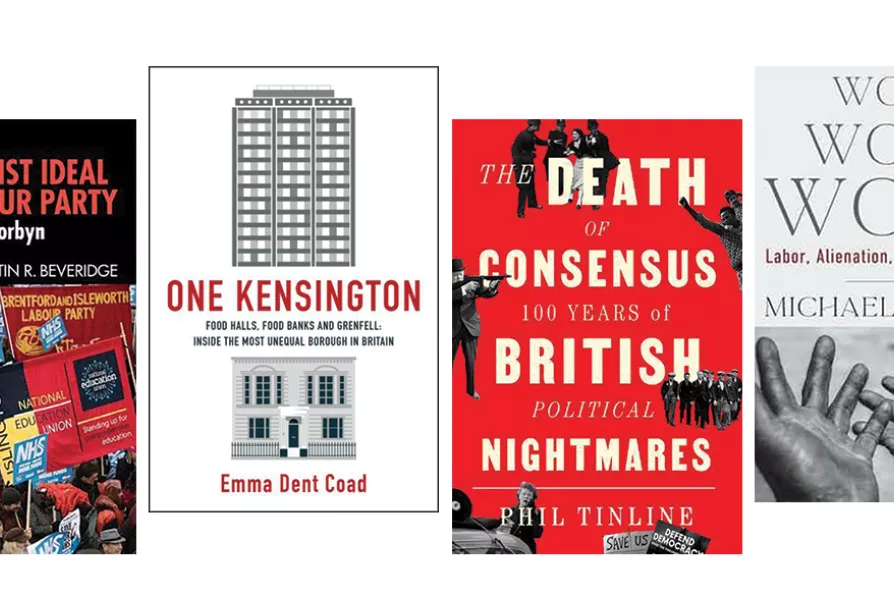

IF ONE character has been more prominent than many in political titles published in 2022, it is the gate-crasher UK parties struggle to evict from their comfort zones: the working class.

This hoary, troublesome vagrant just keeps inveigling its way into politics as the spectre no-one dares name, whether this be during the toxic discourse of Tory extremists or the rambling deliberation of Keir Starmer’s new New Labour.

Yet several books published this year sense the zeitgeist by acknowledging this unwelcome guest at the party forever on the verge of spoiling the complacent liberal democratic chatter with its crude curses.

In some titles, our party pooper turns up in fancy dress, not immediately identifiable but roaming the host’s house nonetheless. It is there, if concealed, in Adrian Bingham’s United Kingdom (Polity), a thematic history that traces the secular decline of a country badly failed by its political establishment.

Looking for moral co-ordinates after a tough year for rational political thinking and shared human morality

Looking for moral co-ordinates after a tough year for rational political thinking and shared human morality

GAVIN O’TOOLE welcomes, and recommends a a candid, evidence-based record of Britain’s role in the slaughter visited by Israel upon the Palestinians