JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

RON JACOBS applauds a reading of black history in the US that plots the path from autonomy to self-governance and then liberation

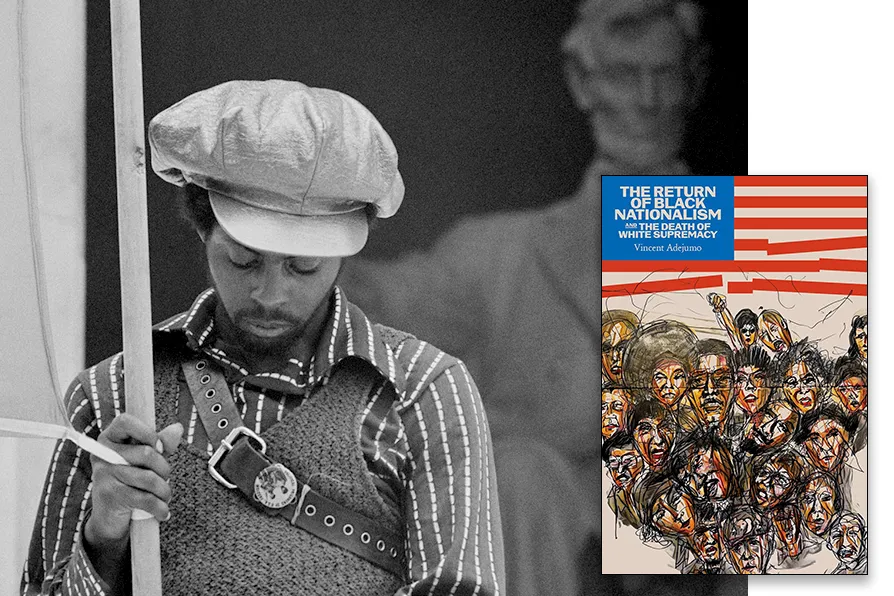

REASONABLE DEMANDS: A member of the Black Panther Party holding a banner for the Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention in front of the Lincoln Memorial, June 1970 [Pic: Library of Congress/CC]

REASONABLE DEMANDS: A member of the Black Panther Party holding a banner for the Revolutionary People's Constitutional Convention in front of the Lincoln Memorial, June 1970 [Pic: Library of Congress/CC]

The Return of Black Nationalism and the Death of White Supremacy

Vincent Adejumo, Feral House, £27.99

IN his book, Vincent Adejumo defines black power as self-determination: “What power means for black people in America is that blacks would have more autonomy and not be forced to beg other groups for basic needs and survival.”

He precedes that definition by insisting that black power does not mean the subjugation of other ethnic and racial groups, unlike existing white supremacy which depends on that subjugation for its grip on power. His definition is one founded in the history of black people in the United States, from the Reconstruction to Marcus Garvey and onward to Tulsa, Oklahoma’s “Black Wall Street”, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence and beyond. The path he suggests based on this history is one that would install economic autonomy leading to self-governance and then liberation.

In the 200 or so pages preceding the above quote, Adejumo discusses the similarities and differences between pan-Africanism and African internationalism using the writings and statements of WEB DuBois (among others) to explain the former, and those of Kwame Nkrumah to explain the latter.

He reflects on the meaning of school integration in a white supremacist society, both acknowledging and questioning the rationales provided by African-Americans who favoured integration and those who oppose it. In essence, the latter position can be summed up by asking the question: why spend so much money moving black students to white schools instead of using those funds to improve the schools in African-American neighbourhoods? Is the white supremacist fear of a black-centered education behind what is presented as a well-meaning effort to improve literacy in African-American communities? Is integration in this manner merely a continuation of the what Adejumo calls “education for domination?”

In asking these questions, one cannot help but go deeper and attempt to answer the greater question as to whether US society — economic, political and cultural — can ever be a society that includes black people in the same way it has incorporated white-skinned immigrants from Europe.

Although the author’s skepticism in this regard underlies his text, the history he provides is a comprehensive look at how black residents of the US have confronted this question over the years. As noted above, the author is wide-ranging in his exploration of that history: from Booker T Washington to Charles Rangell, from Marcus Garvey to the African People’s Socialist Party and beyond.

Constantly informing the questions surrounding the self-determination of black people in the US is the history of those whose predecessors were enslaved by the power structure of white supremacy and colonialism. One cannot truly engage in any honest discussion of black America’s future without placing this history and the financial realities it demanded at that discussion’s forefront.

Many US residents believe that reparations are the essence of any reconciliation, any move beyond the stasis the nation has been in regarding its history of the buying, selling and breeding of other human beings for profit. In its discussion of reparations, Adejumo provides a brief history of attempts to gain financial repair for the economic harm done by white America to its black residents.

It also demands something the author labels political repair; his discussion of this concept quotes Martin Luther King Jr. and Tupac Shakur while referencing the lack of economic independence in black communities and the manipulation of laws relating to criminal activities so that black residents of the US are incarcerated at much higher rates than their white-skinned counterparts.

This would be a powerful and controversial book at any point in US history. It becomes even more so in the current period when white supremacy is on a rampage hoping to bring back the days of legal apartheid and judicial legitimisation of white domination. It is a political statement and a history the likes of which most US residents have never heard, much less considered.

The early days of slave ships and beatings are contrasted with the world of police murders of unarmed African-Americans and the occupation of their neighbourhoods by police forces in the service of a power structure founded and enriched by institutional slavery.

By placing black nationalism at the center of his text, Adejumo has given the reader an opportunity to read and consider the US past, present and future. To use his words: “If a black nationalist party with the basic tenets of nationalism is not established with the end goal of killing white supremacy, the devolution of African Americans into second-class citizenship in perpetuity will be the bleak reality for future generations.”

Ron Jacobs’s latest book, titled Nowhere Land: Journeys Through a Broken Nation, is now available. He lives in Vermont. He can be reached at: ronj1955@gmail.com