JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

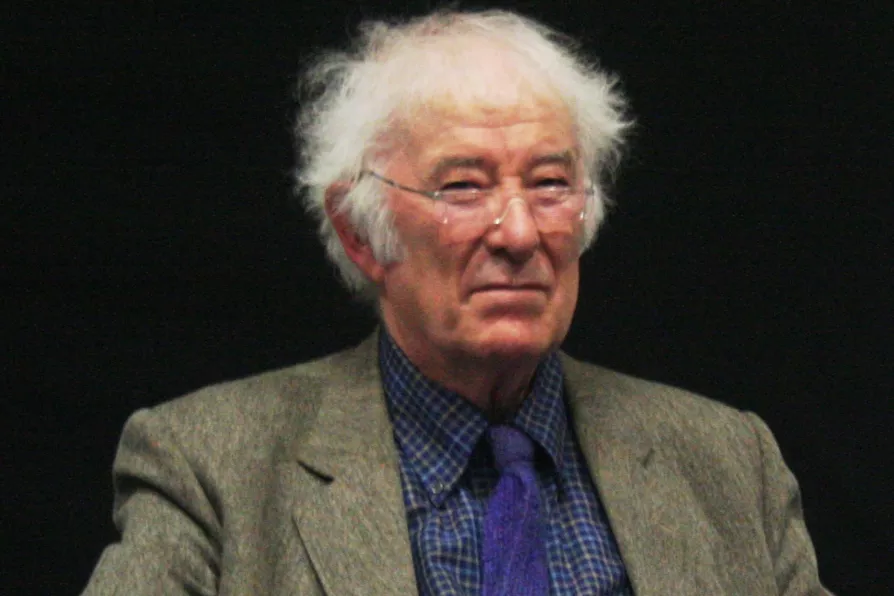

On Seamus Heaney

RF Foster takes the measure of one of the most powerful wordsmiths of the 20th century

NATIONAL TREASURE: Seamus Heaney

NATIONAL TREASURE: Seamus Heaney

THIS survey of the life and work of the late Seamus Heaney, Ireland’s national poet and Nobel Laureate, was published in the month of John Hume’s death — another Nobel Prize winner and a schoolmate of Heaney’s — and the book gives a timely perspective on the Northern Irish Troubles as experienced and responded to in Heaney’s work.

Its author, historian RF Foster, charts Heaney’s developing awareness of the need to create form out of

the chaos of atrocity, not only in his writing but in his choices of allegiance and he chooses, beyond any cause, the independence of the artist in following the dictates of his art form.

Similar stories

Ben Cowles speaks with IAN ‘TREE’ ROBINSON and ANDY DAVIES, two of the string pullers behind the Manchester Punk Festival, ahead of its 10th year show later this month

This is poetry in paint, spectacular but never spectacle for its own sake, writes JAN WOOLF

JOHN GREEN surveys the remarkable career of screenwriter Malcolm Hulke and the essential part played by his membership of the Communist Party

ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement