Climate activist and writer JANE ROGERS introduces her new collection, Fire-ready, and examines the connection between life and fiction

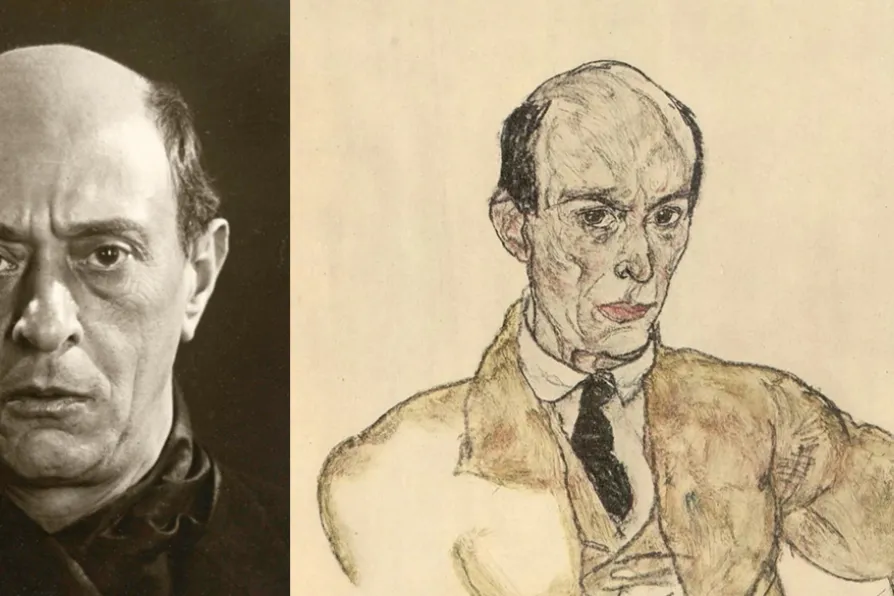

(L to R) Arnold Schoenberg, 1927, photographed by Man Ray and drawn by Egon Schiele, 1917

(L to R) Arnold Schoenberg, 1927, photographed by Man Ray and drawn by Egon Schiele, 1917

FEW figures throughout history have managed to have the musical impact of Arnold Schoenberg. Unlike older giants, like Beethoven, Schoenberg, despite having a huge admiration, still suffers the ire of conservative ears and being the “sole” reason for disliking modern music (ignoring that Schoenberg has not been modern for decades).

Born in Vienna in 1874, Schoenberg’s music grew and developed amid the cultural growth and energy of turn of the century Vienna and he was mostly self-taught.

His early works show the influence of Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss, a rich romanticism and tempestuous music full of energy and drama.

WILL STONE witnesses an experimental piano concerto inspired by the work of a young Jewish victim of the Nazis

CHRIS SEARLE speaks to saxophonist and retired NHS orthopaedic surgeon ART THEMEN

New releases from Nazar, Peter Gregson and Mesias Maiguashca