JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

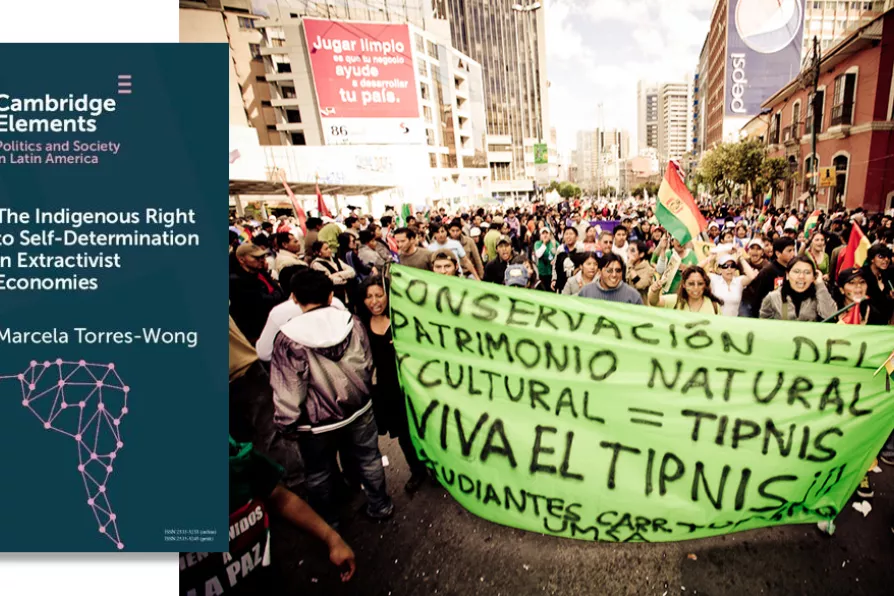

TIPNIS marchers arrive in La Paz, Bolivia, 19/10/2011. Isiboro Secure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS) became the epicentre of a conflict over the construction of a road, initiated by Evo Morales’s administration, that would run through the park. Indigenous peoples from the lowlands opposed the scheme, and, together with their counterparts in the Andean region, organised a march that was violently dispersed by the Bolivian armed forces.

[Szymon Kochanski/Flikr]

TIPNIS marchers arrive in La Paz, Bolivia, 19/10/2011. Isiboro Secure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS) became the epicentre of a conflict over the construction of a road, initiated by Evo Morales’s administration, that would run through the park. Indigenous peoples from the lowlands opposed the scheme, and, together with their counterparts in the Andean region, organised a march that was violently dispersed by the Bolivian armed forces.

[Szymon Kochanski/Flikr]

The Indigenous Right to Self-Determination in Extractivist Economies

Marcela Torres-Wong, Cambridge University Press, £17

THE resounding vote by Ecuadorians to stop the development of all new oil wells in the Amazonian Yasuni national park is an emphatic signal that indigenous people have steered the global debate on extractivism to a historic juncture.

The binding referendum decision permanently prohibits oil drilling in the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini (ITT) oil project and is a major blow to the fossil fuel industry led by Ecuador’s own state oil company, Petroecuador.

The move has fuelled hysterical warnings by mainstream economists that it will further harm this cash-strapped South American country, with the praetorian guard of global capitalism, the credit ratings agencies, already penalising Quito.

LEE BROWN highlights the latest attempts to undo progressive reforms instated during the presidency of Rafael Correa

FRANCISCO DOMINGUEZ says the US’s bullying conduct in what it considers its backyard is a bid to reassert imperial primacy over a rising China — but it faces huge resistance

Noboa’s second term looks set to deepen his neoliberal policies: reduced public investment, privatization, cuts to social programmes, and militarisation, says PILAR TROYA FERNANDEZ

Ecuador’s election wasn’t free — and its people will pay the price under President Noboa