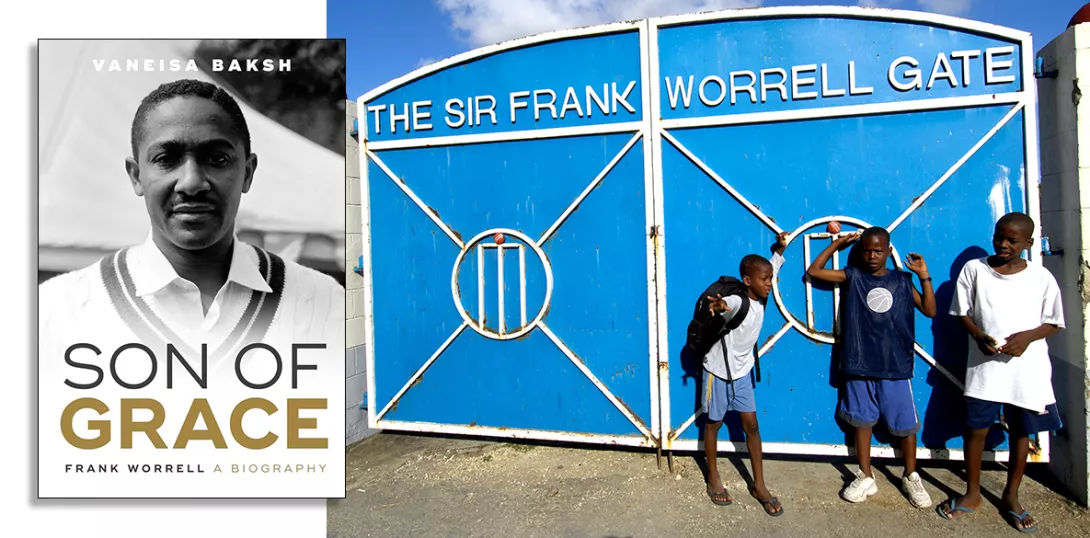

Son of Grace: Frank Worrell – A Biography

Vaneisa Baksh, Fairfield Books, £22

OCCASIONALLY referred to as a “cricketing Bolshevik,” Frank Worrell acted as a powerful agent of change when he became the first permanent black captain of the West Indies in 1960.

He came to that job only after a bruising campaign to reverse the white hegemony in Caribbean cricket — a long-running battle to which, among others, the Trinidadian Marxist CLR James lent his weight.

Yet, as Vaneisa Baksh points out in this thorough new account of his life, Worrell was “contemptuous of politics,” to the point that he attended only two sittings of parliament in newly independent Jamaica after being appointed as a senator there in 1962, giving up the position within two years.

Baksh shows that Worrell’s preference was for the personal rather than the political, and that after he had finished being West Indies captain he believed the best way of using his influence was on the social front, inspiring and cajoling a fresh generation of West Indians into taking hold of their post-colonial destiny.

This is revealed most effectively in the strongest part of Baksh’s book, which covers the post-cricketing years when he took on a senior role at the University of the West Indies and became an informal roving ambassador around the Caribbean and the world.

Worrell died of leukaemia aged 42 in 1967, so primary source materials relating to his personal life, as well as good chunks of his professional existence, are hard to come by. But for the university period Baksh has done well to secure revealing interviews with those who worked and studied with him — not to mention useful letters relating to his work around the time.

She’s unearthed valuable nuggets in other areas too, including hitherto unseen documents from the West Indies Cricket Board, and while this is not the first biography of Worrell, it is certainly the most comprehensive.

At times, however, the focus of the book is shaped too strongly by the fact that Baksh clearly feels she has to make the absolute most of her fresh sources. Thus we get too much coverage of some aspects of Worrell’s life that are relatively unimportant, including an arcane dispute with his university employers over a loan agreement.

That incident might have been better used in miniature, and to make a wider point about Worrell’s carefree attitude to money, but in general Baksh seems reluctant to draw too many conclusions from the material she has gathered.

After a lengthy section on Worrell’s decision to lead a “rebel” tour of South Africa in 1959, for instance, all the author can provide by way of an overall insight is to suggest that “whether Worrell should have considered going to South Africa at all remains hanging over history.”

While such fence-sitting might be seen as a sign of laudable neutrality, it is disappointing that Baksh should not voice her opinion a bit more often, especially given her deep knowledge of the subject, cricket and the Caribbean.

This is especially noticeable at the conclusion of the book, when instead of an attempt to sum up Worrell’s life and achievements, she opts for an oddly introspective look at the ramifications of Worrell’s death for certain members of his close family — and ends there.

Overall, then, a worthwhile and readable effort, but not the definitive biography.