ON February 8 1840 London-born carpenter Samuel Duncan Parnell landed in Port Nicholson, New Zealand. During the journey he met shipping agent George Hunter, who on arrival asked him to build a store at Lambton Quay.

Parnell’s response has entered New Zealand folklore.

“I will do my best, but I must make this condition, Mr Hunter, that on the job the hours shall only be eight for the day. There are twenty-four hours per day given us; eight of these should be for work, eight for sleep, and the remaining eight for recreation and in which for men to do what little things they want for themselves. I am ready to start to-morrow morning at eight o’clock, but it must be on these terms or none at all,” Parnell made himself forcefully clear.

A meeting of carpenters in October 1840 pledged “to maintain the eight-hour working day, and the practice of ducking of transgressors into the harbour.” The hours worked would be between 8am and 5pm.

And so Robert Owen’s maxim of 1817 had become standard practice for the first time in New Zealand.

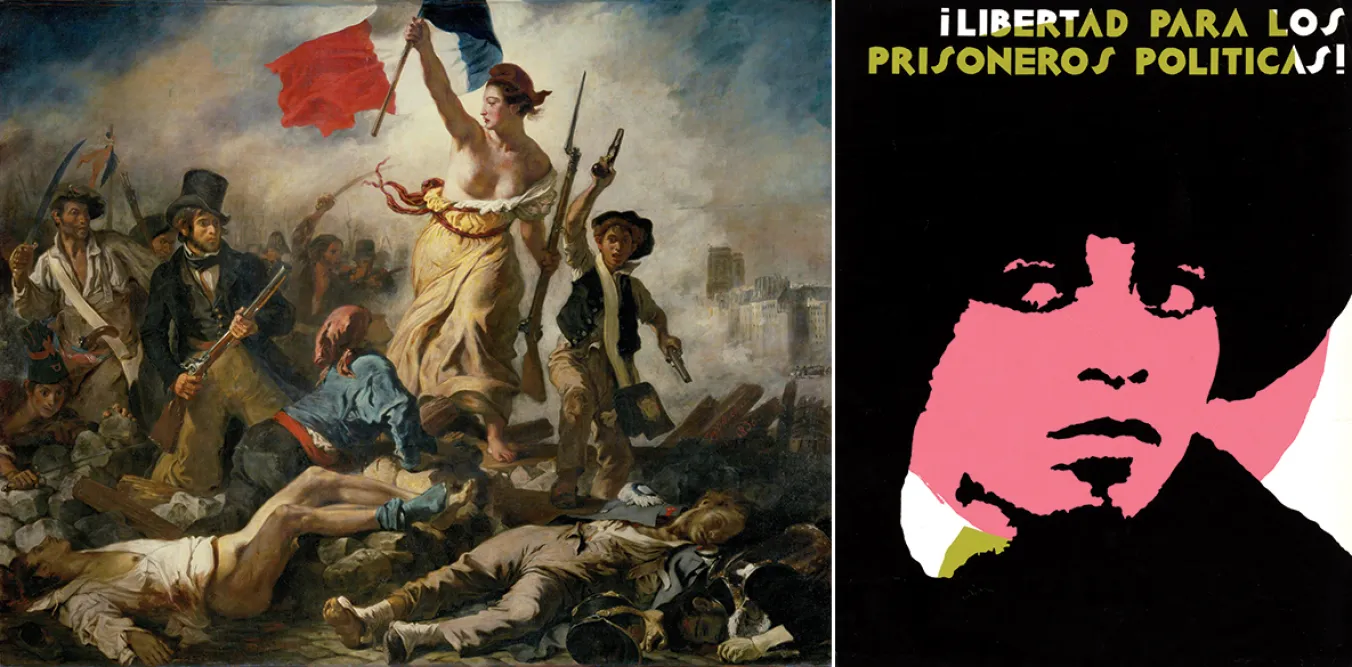

Although not strictly a May 1 achievement the poster celebrates this victory in what was the quintessential struggle of workers the world over — a victory that preceded by over 40 years the establishing of May 1 as the International Labour Day in commemoration of the Haymarket Riot in Chicago in 1886.

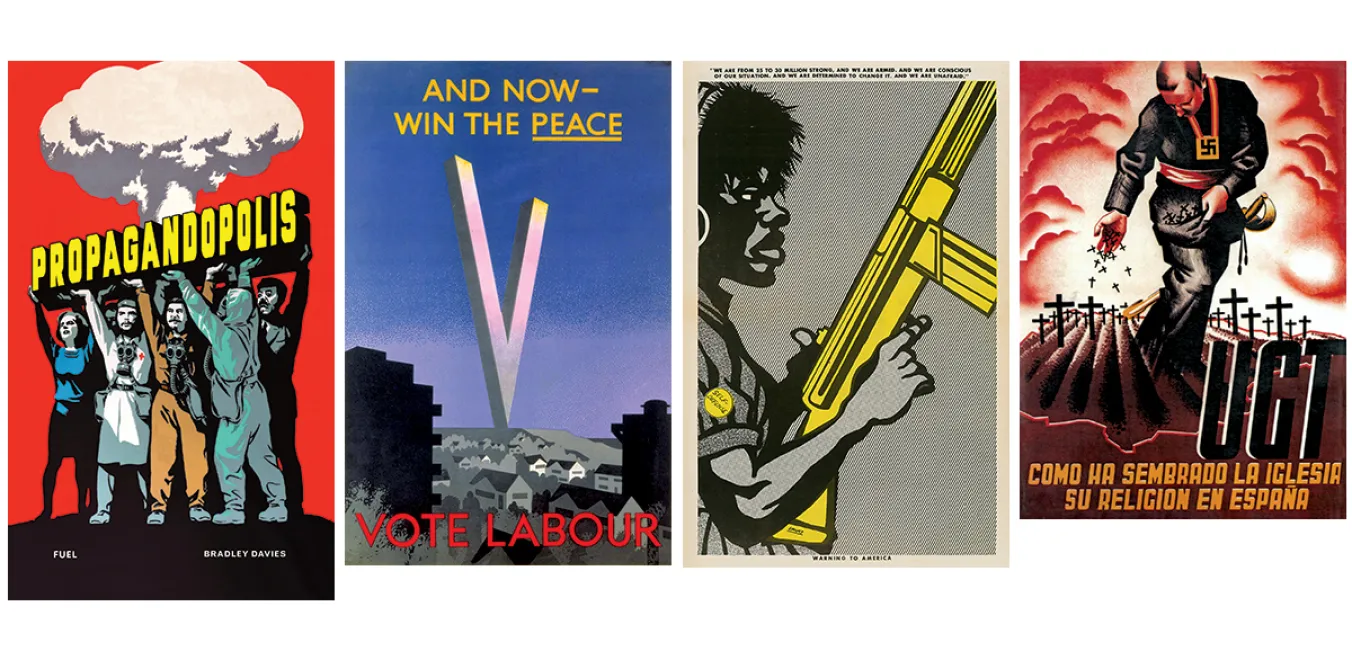

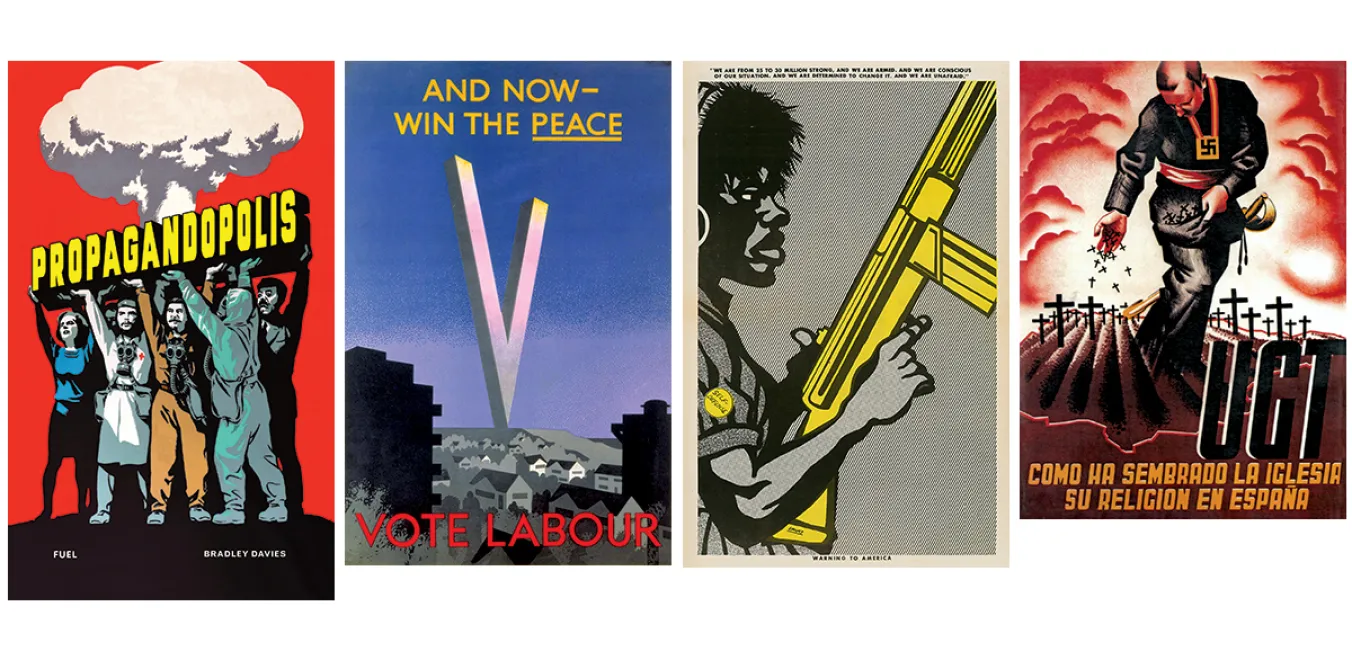

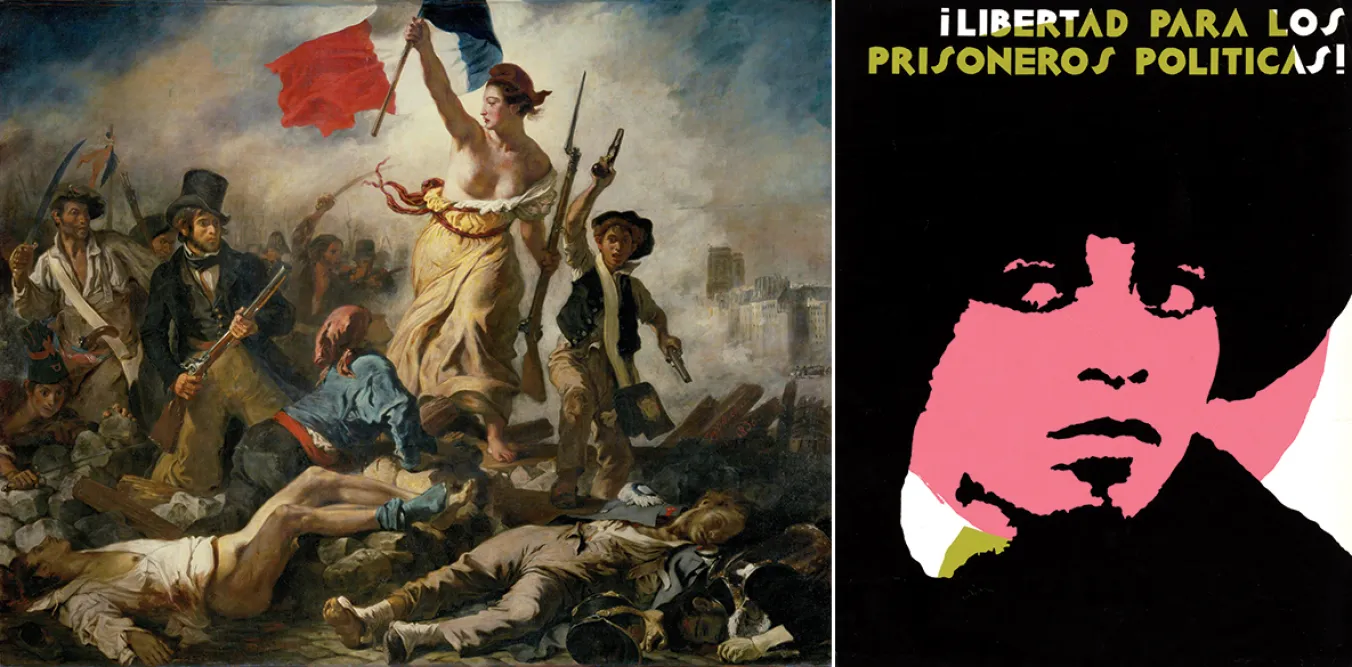

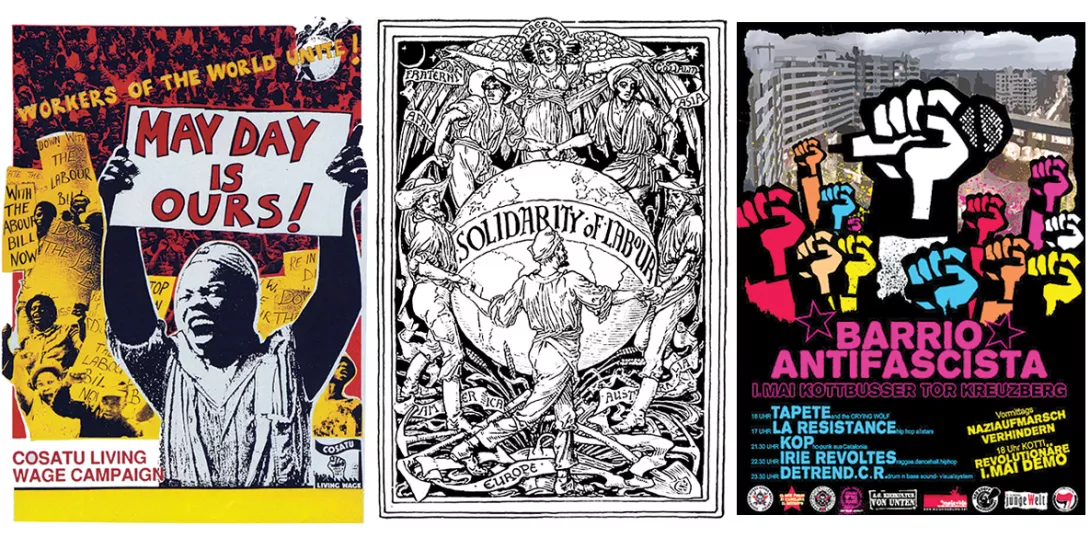

From the animated Cosatu collage to the Cuban, brilliantly minimalist, salutation of the global working class to the Art Nouveau of Walter Crane or the succinctly propagandist and constructivist-lead Rosta, May 1 inspired beguiling creativity.

The delightful Long Live the Fifth Anniversary of the Great Proletarian Revolution, by Ivan Simakov, 1922, with its flowing calligraphy was published to coincide with the Fourth Congress of the Communist International and although not directly observing May 1 it nevertheless encapsulates vividly its spirit of internationalism.

In it the central figure holds a hammer and sickle, an emblem of communism, and a winning design in a competition run by Vladimir Lenin and Anatoly Lunacharsky in 1917. The original included a sword but Lenin objected to its inclusion because of the implicit violence. It depicts celebrating workers from around the globe and various notable landmarks, including Big Ben, the Eiffel Tower, the White House, Hagia Sophia and the pyramids of Egypt.

While a colourful array of fists defines a poster for the Junge Welt sponsored May 1 2009 concert in Berlin’s Kreuzberg neighbourhood, which was violently dispersed by the police with batons and tear gas, it led to an investigation into the recent policing of protest.