The Star's critic MARIA DUARTE recommends an impressive impersonation of Bob Dylan

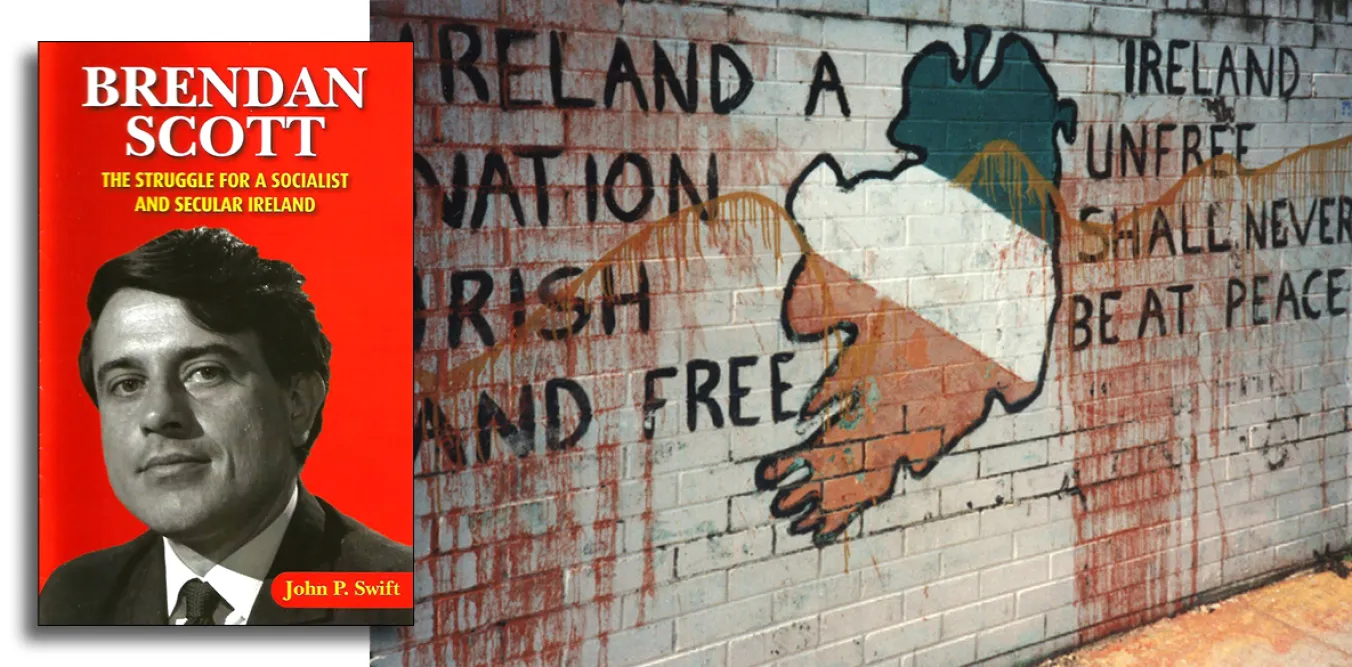

Brendan Scott: The struggle for a socialist and secular Ireland

Excellent biography of inspirational figure on the left

LIKE so many influential revolutionaries, Irishman Brendan Scott (1933-73) threw himself into a lifelong and sustained involvement with what appears to have been a multitude of progressive and grassroots organisations.

Although keen to develop his politics electorally, Scott paid equal attention to strengthening struggles in the workplace and community and, inspiring respect from friend and foe alike, helped develop the Dublin Housing Action Committee, an early supporter for civil rights in the six counties.

He unapologetically admired James Connolly’s vision of an Ireland that was free, united and socialist.

More from this author

STEVEN ANDREW welcomes the third instalment of autobiography by a libertarian socialist whose political work is charged with Gramscian realism

STEVEN ANDREW has reservations about the political slant of an otherwise indispensable guide to life in the Soviet Union

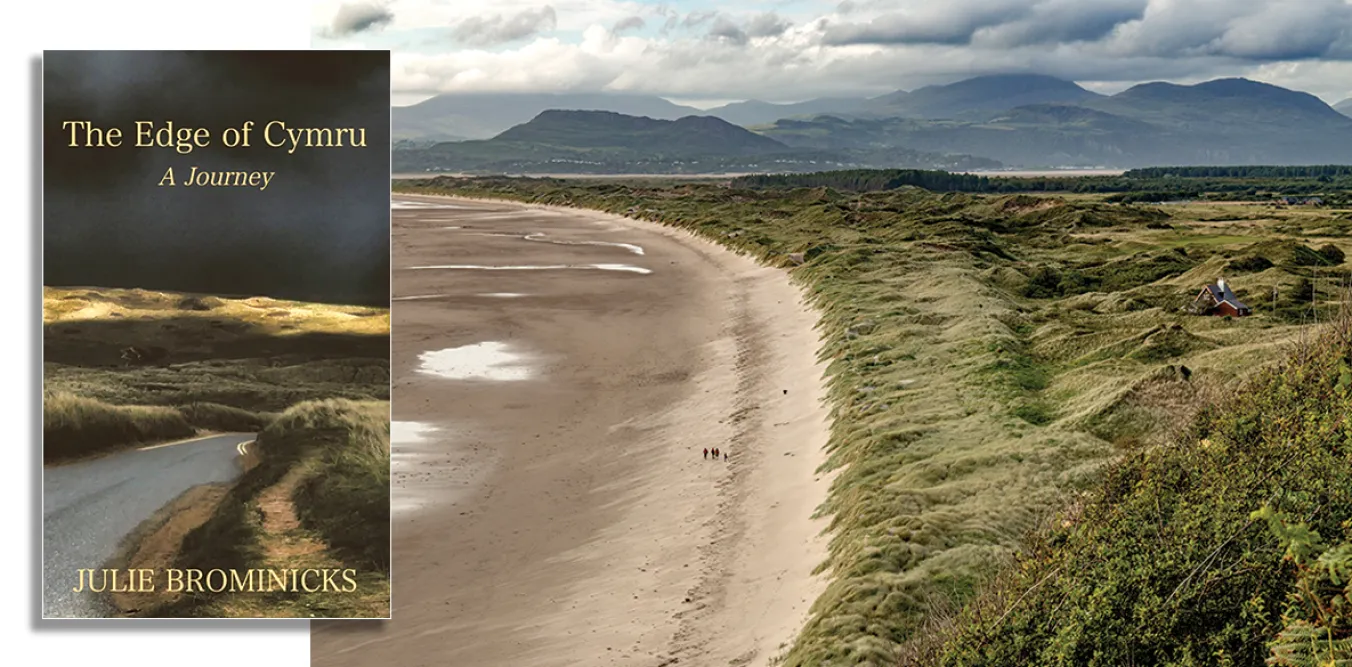

STEVEN ANDREW is inspired to pull on his boots by this engaging and class-conscious account of a trek through Wales

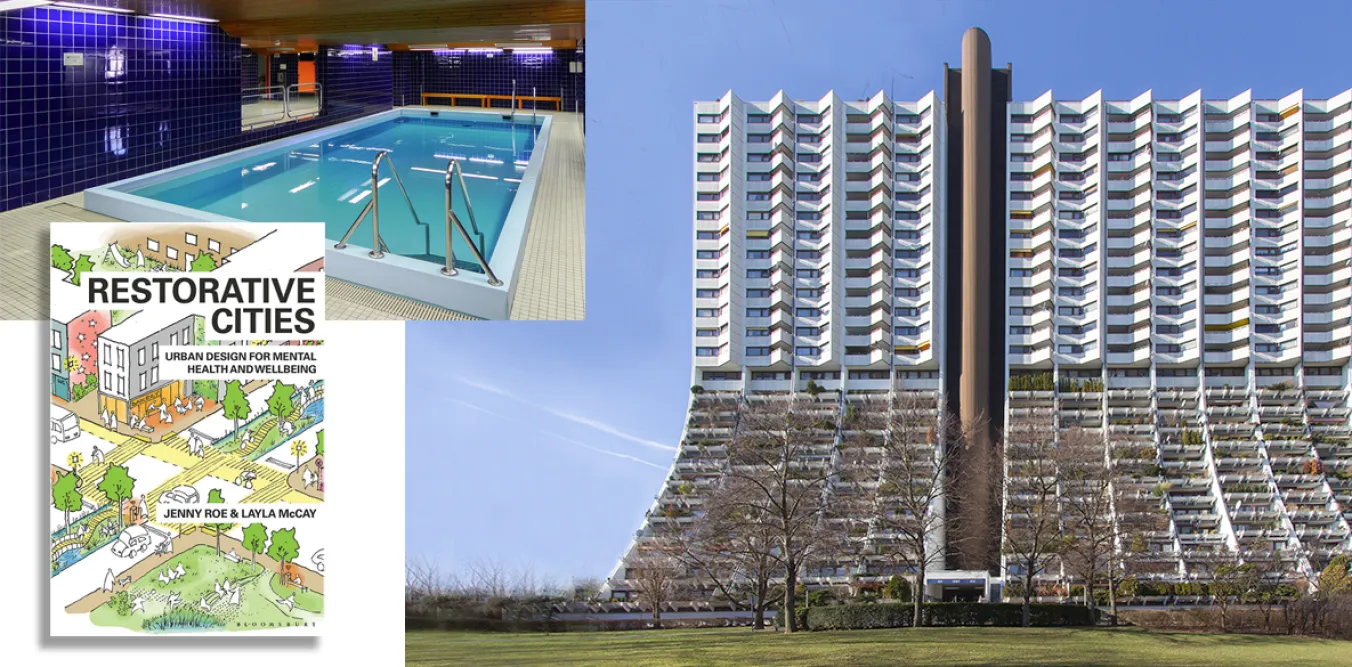

STEVEN ANDREW recommends a book that is a superb example of what has come to be known as engaged urbanism

Similar stories

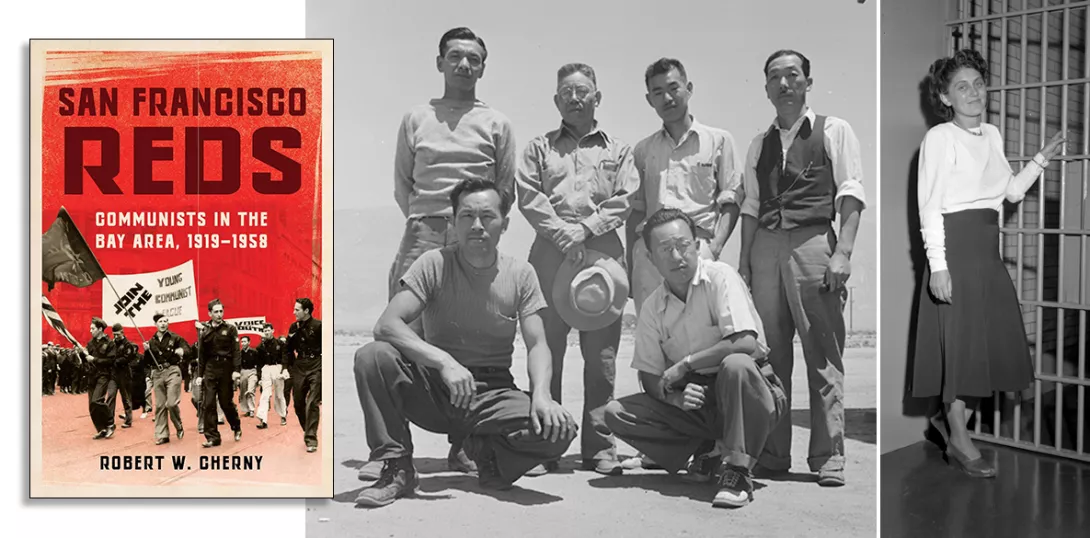

PAUL BUHLE recommends a thorough and necessary history of communist organisation and the difficulties it faced in California

1930-2024

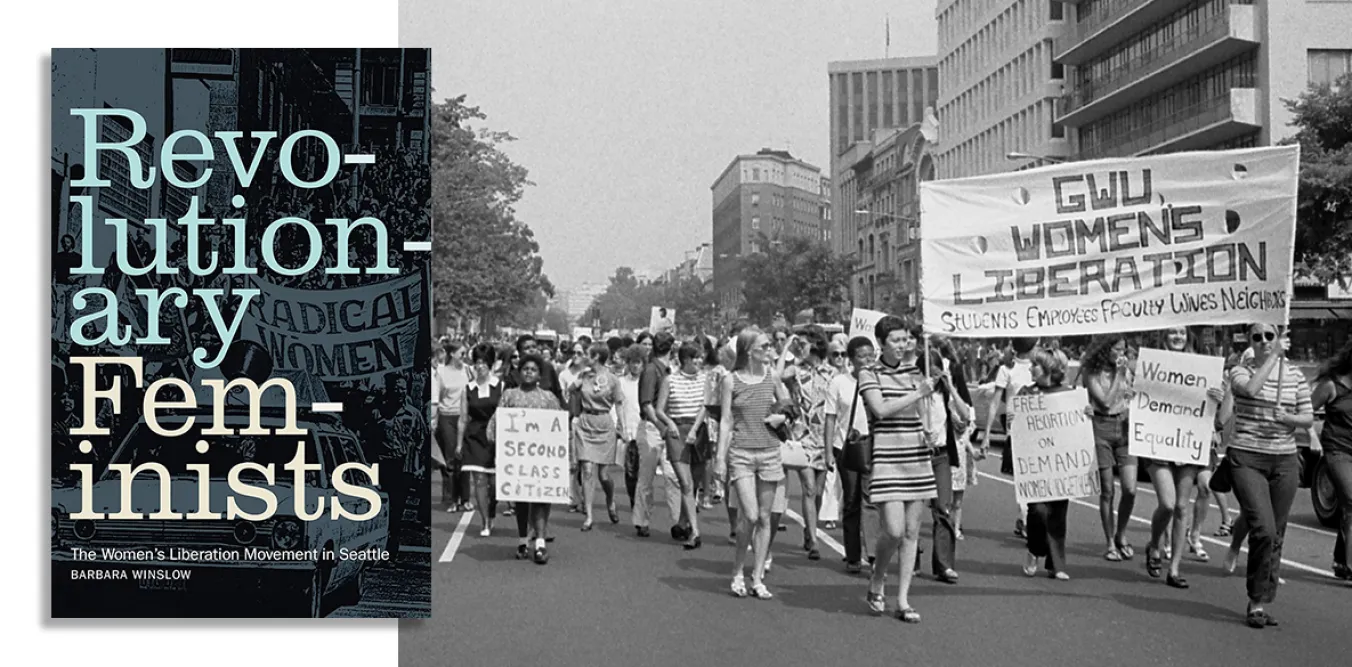

RON JACOBS points out that it wasn’t until anti-imperialist and anti-racist movements formed women’s liberation groups that the fundamental roots of oppression could be addressed