ANDY HEDGECOCK relishes two exhibitions that blur the boundaries between art and community engagement

This is Tory England

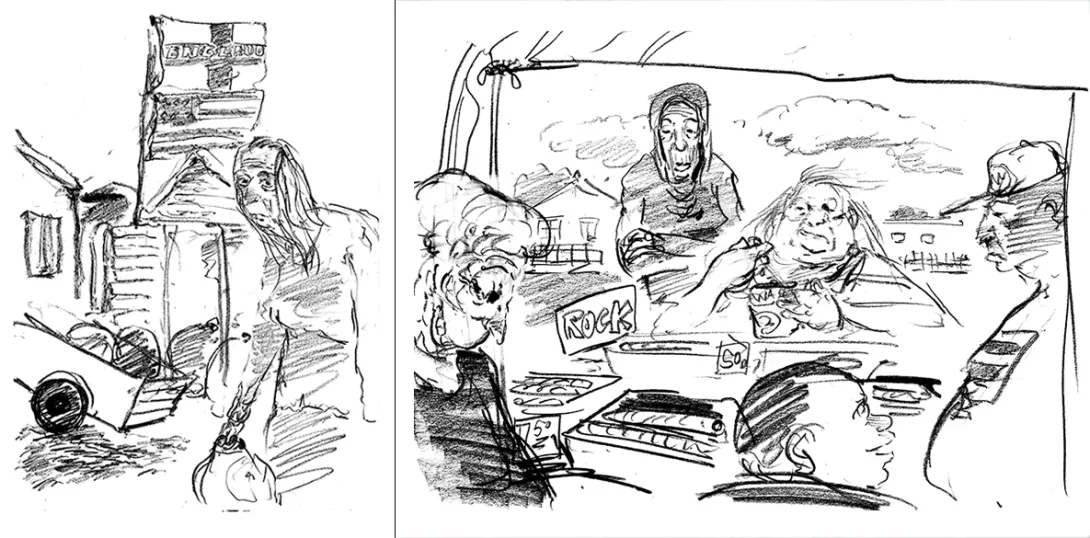

TOM SYKES went to Jaywick in Essex last summer and kept a diary. Here is an extract illustrated by his companion on that journey Louis Netter

WE’VE only been in Jaywick for an hour and we’re sure this is the most deprived place we’ve ever seen, at least in this country. The stats bear this out — 57 per cent of the denizens rely on some form of state benefit to survive.

Besides, you know your town might just be in a spot of bother when a United Nations poverty investigator decides to visit, which is precisely what happened here in 2018.

Professor Philip Alston concluded that Jaywick’s woes had nothing to do with personal idleness, and everything to do with years of public underfunding and the Tory government’s callous universal credit system.

More from this author

Genocide, racism and imperialism are in the Labour Party’s DNA, argues TOM SYKES

A legal case at the ICJ has exposed the role of Indonesian arms sales that were crucial to enabling Myanmar to kill thousands of civilians, reports TOM SYKES

Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jnr has won, using a tech-savvy social media rewrite of his parents’ dictatorship and a troll army to smear his closest competitor — DR TOM SYKES reports on a society seemingly unable to leave its own dark age

TOM SYKES examines the ever-expanding military-industrial-academic complex

Similar stories

MAT COWARD looks at how the bicycle helped spread socialist education and the holiday camp was invented for the benefit of the working class

ANDREW MURRAY visits Nigel Farage’s target constituency and wonders what it is about the seaside town that has put it in Reform UK’s sights

The bard happily finds himself among his piers