VIJAY PRASHAD examines why in 2018 Washington started to take an increasingly belligerent stance towards ‘near peer rivals’ – Russa and China – with far-reaching geopolitical effects

The return of the European Question: what next for Britain-EU relations?

As Starmer hints at closer ties, MARTIN HALL warns of the dangers of creeping alignment and calls for a renewed socialist case for independence from Brussels, especially over the EU’s constraints on economic planning

THE general election in July was the first since 2010 at which Britain’s relationship with the European Union was not central to the debates.

That being said, the issue is far from put to bed. From regular lobbying in the Financial Times and other liberal media outlets, through to the review of the Trade and Co-operation Agreement scheduled for 2025, and the establishment of the European Political Community in 2022, Britain’s ruling class is and will be pushing for greater integration.

Given the architect of Labour’s calamitous Brexit policy from the 2019 general election is now the prime minister, this slide towards increased alignment will only increase in speed.

More from this author

MARTIN HALL admires a remarkable film that concentrates on the human impact of gender dysphoria

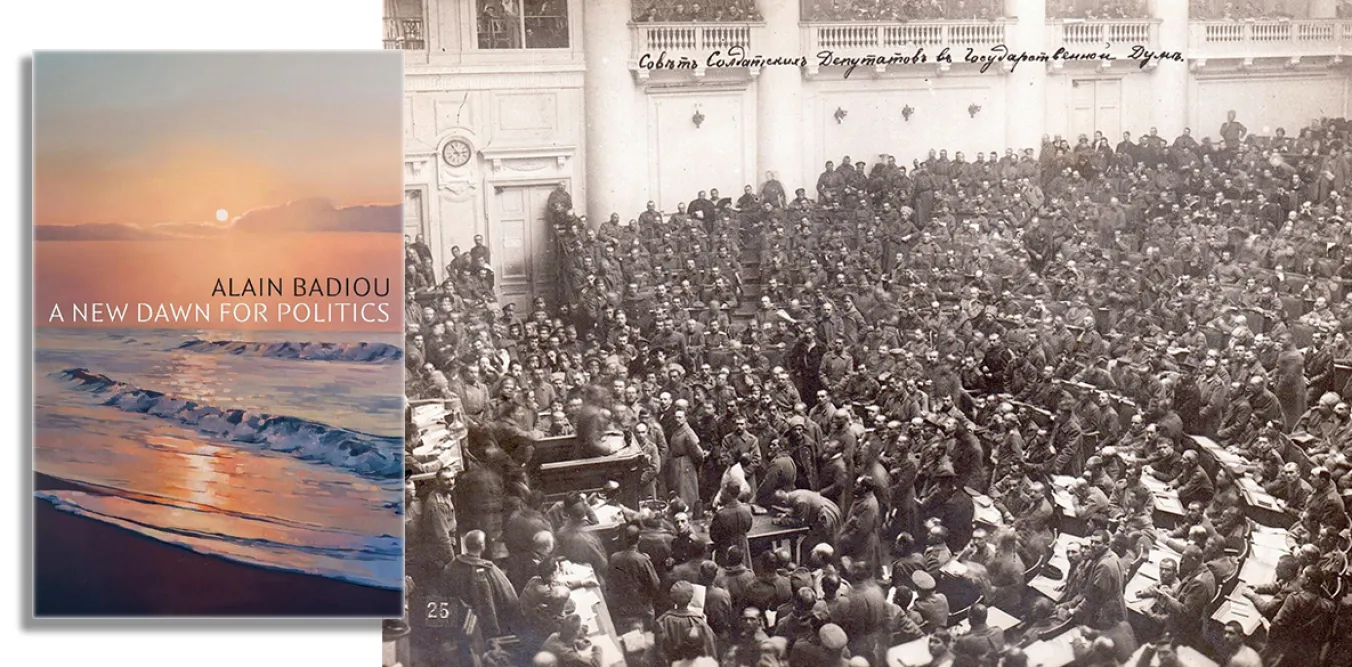

MARTIN HALL steps gingerly through a work of French political theory, picking out the gems

Until such time as a new parliamentary vehicle for the working class emerges, socialists should continue to vote Labour, argues MARTIN HALL

Why did Labour go from from a ‘People’s Brexit’ position to a politically incoherent Remain-sympathetic fudge – and how can we stop the impending disaster, asks MARTIN HALL

Similar stories

From Maoist student provocateur to Brussels bureaucrat, Jose Manuel Barroso now emerges to push European rearmament and the Atlanticist dream of a forever war with Russia to the tune of billions of euros, writes NICK WRIGHT

The French president and the European Central Bank have identified ‘more of the same’ neoliberal agenda as the answer to the EU’s woes – but can post-Brexit Britain grasp the opportunity to reject continued austerity, asks NICK WRIGHT

We don’t need to peer into shadowy, secretive corners for extremist politics here in Britain — it is growing openly in the mainstream of the Tory Party, and without meaningful left opposition, things will only get worse, warns BEN CHACKO