SIMON PARSONS is charmed by a hilarious tender show that will open the eyes to the delights and possibilities of puppetry

BRENT CUTLER is persuaded by a new account of the rise of Christianity, and the fall of the Roman empire

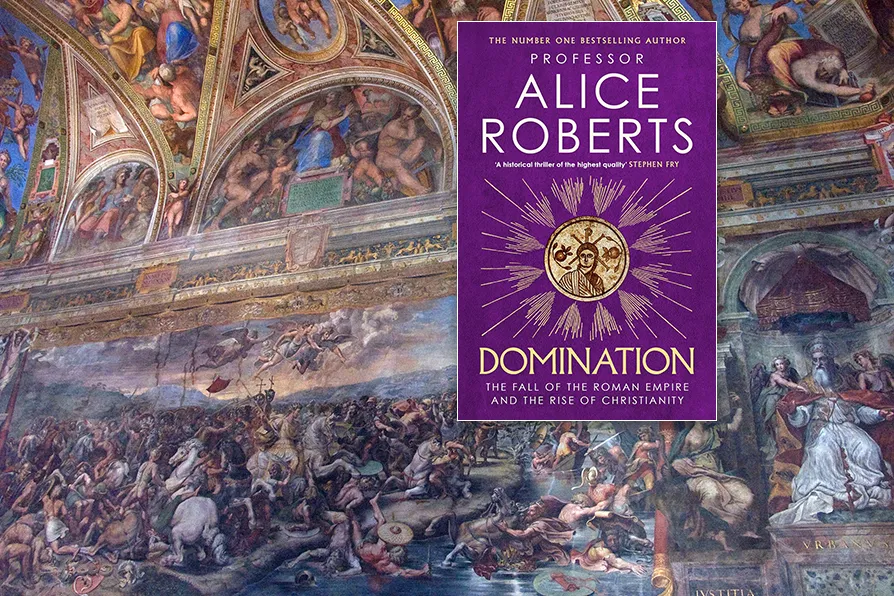

RE-WRITING HISTORY: The Battle of Milvian Bridge, in the Apostolic Palace, Vatican City, depicting Constantine’s defeat of Maxentius under supposedly Christian banners [Pic: Jean-Christophe BENOIST/CC]

RE-WRITING HISTORY: The Battle of Milvian Bridge, in the Apostolic Palace, Vatican City, depicting Constantine’s defeat of Maxentius under supposedly Christian banners [Pic: Jean-Christophe BENOIST/CC]

Domination – The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire and the Rise of Christianity

Alice Roberts, Simon & Schuster, £22

IN her latest book Alice Roberts explores the role of Christianity within the late Roman empire. She unveils a process of continuity and change, with Christianity being the most consistent force of continuity.

Her work uses archaeology, numismatics (the study of coins), and the study of symbols as primary sources of information. She points out, probably correctly, that written accounts from the period may not be entirely reliable. The book does, however, contain some careful analysis of primary written sources, which she quite correctly describes as “reading between the lines.”

Christianity, originally a sect within the Jewish religion, is a fusion of Greek Stoic philosophy and Judaism. It officially became the religion of the Roman empire in AD 380 under the Emperor Theodosius after much of the groundwork for the conversion of the empire to Christianity had taken place under Constantine the Great (AD 306 to 337).

Roberts points out that Rome’s shift from polytheism to Christianity may have been an even more gradual process than previously thought. Constantine’s banner at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (AD 312), that was subsequently interpreted as denoting Christianity, may itself have been a pre-Christian symbol. This event indicates a process whereby both the Roman empire was becoming Christianised and, at the same time, Christianity was becoming Romanised through a fusion of pre-existing symbols and elite-level manipulation. This is particularly important in a period of low literacy.

The Roman empire in the West ended in AD 476, a century after it adopted Christianity. Its demise was founded on a combination of internal and external factors; population pressure from outside its borders, internal strife and climate change. It was gradually replaced by a set of new kingdoms, some which morphed into modern nation states. Roberts argues against the idea of a complete collapse.

According to Roberts, the church was a “semi-autonomous civil service — maintaining control whilst kings and emperors fought amongst themselves. It also provided positions for members of elites, both new and old and operated across borders.”

Essentially, members of elite Roman families may have embedded themselves within the Church apparatus, thus surviving the so-called Barbarian invasions, whilst the church provided legitimacy for the new rulers who replaced the empire.

Overall Roberts gives a materialist explanation for the success of Christianity, which may appear controversial to the religiously devout. Christianity’s success came from its ability to provide a social welfare and eventually a landholding role which members of the elite could buy into as a means of acquiring lucrative employment.

In the later chapters of the book she describes the church as a firm. This, combined with Christianiy’s spiritual appeal — offering eternal life — enabled the church to outlive the Roman empire, at least in the West, and still able to be a powerful institution for millenia to come.