PRAGYA AGARWAL recommends a collection of drawings that explore the relation of indigenous people to the land in south Asia, Africa and the Caribbean

The portrait of Elisabeth Lederer carries a deep personal and political history. BENEDICT CARPENTER van BARTHOLD explains

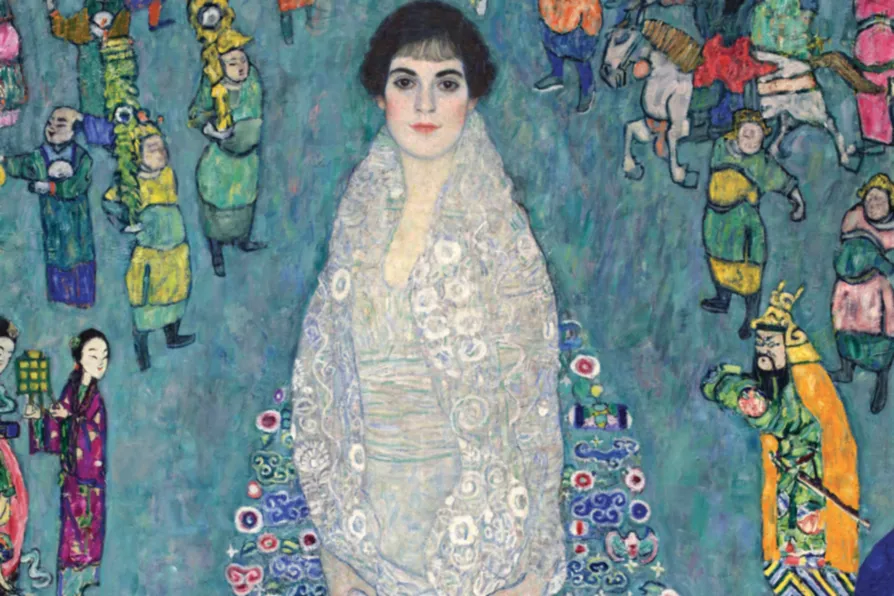

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, 1914-1916 (cropped)

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, 1914-1916 (cropped)

LAST week Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer has sold to an anonymous phone bidder for $236.4 million (£180.9 million) at Sotheby’s New York.

Only Leonardo Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi has achieved, in 2017, a higher hammer price. For modern art, Klimt is the uncontested champion.

What’s more, this record was achieved despite a cooling global art market, and with Klimt lacking the universal household recognition of Da Vinci in much of the world.

The painting is valued so highly because it carries a deep personal and political history — and because the artist’s incredible skill once helped it serve as a life-saving disguise.

Standing over six-foot tall, the canvas depicts Elisabeth Lederer, daughter of Klimt’s most important patrons, August and Szerena Lederer. Painted between 1914 and 1916, it represents the artist’s late, ornamental style.

Elisabeth is swaddled in a billowing, diaphanous dress, nestled within a textured and ornamental pyramid, an implied imperial dragon robe. The upper half of her torso is ensconced in an arc of stylised Chinese figures. The effect reminds me of a halo in an icon (religious images painted on wooden panels).

The setting is fantastical, abstracted, unreal, ornamental — above all, rich. Despite the jewel-like setting, Elisabeth’s face is painted with a striking, psychological realism. Her expression is detached, enigmatic, perhaps isolated. Her hands seem fretful.

It is hard not to project meaning with the benefit of hindsight, but she seems to gaze out from a world of immense Viennese wealth, a world unknowingly on the brink of annihilation.

The Lederers were a prominent Jewish family. After the 1938 Anschluss (the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany), they faced persecution. The family scattered. But Elisabeth remained, divorced and isolated, in Vienna.

Classified as a Volljudin (“full Jew”) under the Nazi regime’s anti-semitic rule, she faced a likely death. In desperation, she circulated a rumour that she was the illegitimate child of Klimt, the Austrian and Aryan painter of her earlier portrait.

To aid this endeavour, her mother Szerena, who had fled to Budapest, swore an affidavit that Elisabeth’s biological father was not her Jewish husband, August, but Klimt, a notorious philanderer. The claim was not without plausibility. Klimt had a long personal relationship with the Lederer household. Elisabeth’s portrait is itself a document of this interest and closeness.

The Nazis, eager to reclaim Klimt’s genius for the Reich, accepted the fabrication. If Elisabeth was not a “full Jew” but instead a Mischling (half-Jewish), then the painting itself could be reclassified as an Aryan work of art. With Elisabeth’s desperate sleight of hand, both she and the painting were saved.

Aided by her former brother-in-law, a high-ranking Nazi official, Elisabeth was legally reclassified as illegitimate and “half-Aryan.” This lie successfully shielded her from the death camps, uniting art history, gossip and survival in a single legal document.

This deception also ensured the painting’s physical survival. The Lederer Klimts fell into two camps. The Jewish portraits were degenerate art, and were set aside to be sold. But the rest were considered important heritage.

While the Nazis moved the bulk of the looted Lederer collection to the castle Schloss Immendorf for safekeeping, Elisabeth’s portrait remained in Vienna due to its newly contested “Aryan” status, in limbo.

In May 1945, SS troops set fire to the Schloss, incinerating over a dozen Klimt masterpieces, including a painting of Elisabeth’s grandmother. But in Vienna, the painting of Elisabeth, and another of her mother, Szerena, survived. This brutal and arbitrary destruction is what makes Elisabeth’s painting such a statistical anomaly.

As one of only two full-length Klimt portraits remaining in private hands, its scarcity is near absolute. For collectors, this auction was an inelastic opportunity. On Tuesday November 18, if you wanted to own a major Klimt portrait, it was this one, or none.

The work’s post-war provenance further amplifies its value. The painting was restituted to Elisabeth’s brother Erich in 1948. In 1985, it was purchased by the cosmetics billionaire Leonard A Lauder.

Unlike many investment-grade masterpieces that are sequestered in free ports, unseen and treated as financial assets, Lauder lived intimately with the work for 40 years, reportedly eating lunch beside it daily.

He frequently loaned it anonymously to major institutions, ensuring its visibility to art history and scholarship, but without testing its value on the market for four decades.

Lauder’s loving stewardship added a premium, presenting the work not just as a commodity, but as a cherished, well-documented piece of cultural heritage.

Ultimately, the $236.4 million price tag reflects a value proposition that transcends simple supply and demand. The anonymous buyer has acquired an object of extreme aesthetic power, but also a tangible relic of resilience. It is a painting saved by a daughter’s lie, a mother’s perjury, the vanity and cupidity of an odious regime, emerging intact from the wreckage of WWII.

In a market characterised by hype and speculation, this sale rewards deep historical density and incredible technical prowess. Elisabeth’s portrait, which is both monumental and deeply personal, opens a window to the tragic heart of the 20th century.

This legacy should not be financialised, but it is disturbing to speculate to what extent its dark past is reflected in the hammer price. Let’s hope the new owner treats the work as lovingly as her previous custodian. The painting deserves to be shared with the world.

Benedict Carpenter van Barthold is a lecturer at School of Art & Design of the Nottingham Trent University.

This article is republished from TheConversation.com under a Creative Commons licence.

![]()