MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review "Wuthering Heights", Little Amelie or the Character of Rain, Crime 101, and Stitch Head

KEVIN DONELLY considers the strategies by which a major black US artist asserts the place of African-Americans in visual culture

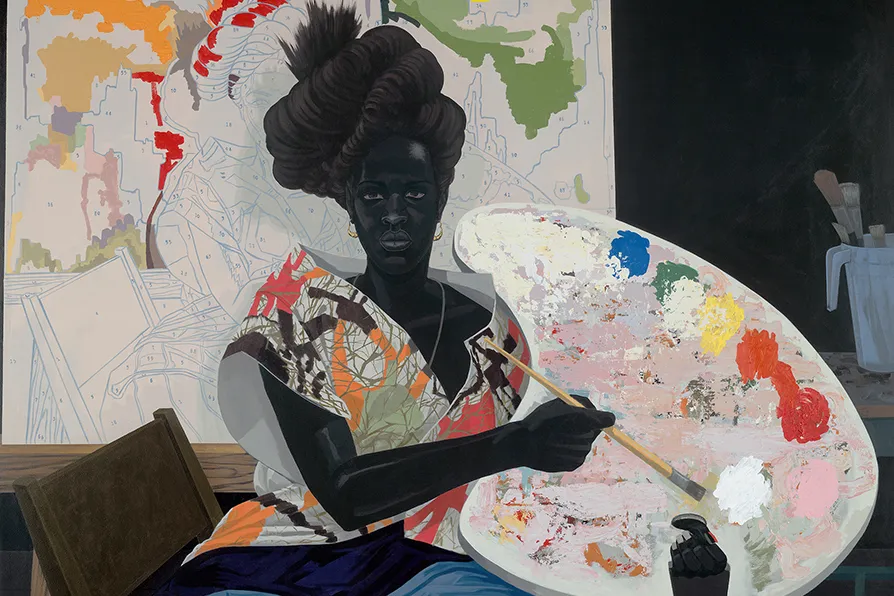

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled, 2009. [Pic: Yale University Art Gallery, © Kerry James Marshall]

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled, 2009. [Pic: Yale University Art Gallery, © Kerry James Marshall]

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories

Royal Academy, London

★★★★★

“But what exactly is a black. First of all, what’s his colour?”

Jean Genet’s question has been taken up and explored extensively in the work of the artist Kerry James Marshall, who has a major exhibition currently running at the Royal Academy until January 18 2026.

One of the leading lights of the Black Arts movement in the United States, Marshall is known for his large-scale figurative work depicting aspects of Afro-American history and culture, and which encompass a wide range of subject matter: civil rights, black power, slavery and colonialism.

A central theme running throughout his work is this idea of “blackness,” as in utilising “difference” as an “oppositional force,” in both a philosophical and an aesthetic sense, to dominant “Western” conceptions of art. His paintings have therefore sought to reappropriate “black” from its history as a negative term, making a black aesthetic “visible” through the narratives contained within his work (and rendering black people visible as a consequence).

A key example here is his painting “School of Beauty, School of Culture” (2012), in which he replaces the skull in Holbein’s “The Ambassadors” with a “classic” representation of “white” beauty, therefore exploring how the “beauty myth” runs along racialised lines. The other figures in the painting then become the “ambassadors” of the knowledge that “black” is also beautiful.

[Pic: Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: Sean Pathasema]

Although his paintings touch on allegory and symbolism, they are easy to “read” politically, depicting fairly straightforward representations of the political and social experiences of being black in the US and/or in a colonial context. For example, in the exhibition, there is the painting of the rebel slave Nat Turner, which is graphic in its depiction of bloody rebellion. They are not naturalistic, but “rhetorical figures that inhabit a realist space” to quote the artist.

However, in a recent interview in the Guardian (September 22), Marshall, paradoxically, expressed some disquiet about being labelled as a “political artist.” “My priority,” he says, “is people.”

An example of a “people painting” here could be “Untitled (Blanket Couple)” (2014), which depicts a seemingly idyllic scene of two figures reclining in the sun. However, overshadowing the figures is the shadow of a tree. It is barren, possibly representing the fact that it is always “winter in America” for black people?

The exhibition is also structured to suggest a number of themes. For example, the display in the central gallery is dedicated to images of the “Middle Passage.” This, of course, is a reference to the Atlantic crossing conducted as part of the international slave trade. However, it has also been used by Paul Gilroy in his book The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Verso, 1993) in which the “journey” is (re)defined in terms of (cultural) “routes” as much as (ethnic) “roots,” creating “transnational” connections, affiliations and tensions.

For Gilroy then, identity is contingent and diasporic, and Marshall has explored the hybrid nature of just such an identity by combining African aesthetics with Western traditions in art — in relation to an exploration of the “double consciousness” experienced by Afro-Americans living in the United States.

In the exhibition, Marshall explores this “complex reality” with his painting “Abduction of Olaudah and His Sister,” depicting children abducted into slavery. The work is based on Olaudah Equiano, the 18th-century writer who was abducted from Nigeria, crossed the Atlantic, and ended up in London as a free man.

Moving on to the main theme of the exhibition, “The Histories” could simply be defined in a binary way, as referring to history in the context of colonial/anti-colonial struggles for example. However, “histories” suggests a “plurality” of narratives.

This also reflects Marshall’s view of history: “It’s always more complex” as he states in the interview. For example, part of his work shown in the exhibition includes paintings which deal with the involvement of black slavers – an often overlooked or ignored aspect of the history of the international slave trade.

As Marshall states in the interview: “They don’t fit the narrative of white people evil, black people good. It doesn’t fit.” For Marshall, painting performs a function in that “it can be a catalyst for investigating or taking a look at areas of history that people tend to not find their way to.”

All in all, a major exhibition by “arguably America’s greatest living painter” (to quote the Guardian), who has the power to both disturb and inform; and also render the invisible, visible.

Runs until January 18 2026. For more information and tickets see: royalacademy.org.uk