GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

JOHN GREEN welcomes a remarkable study of Mozambique’s most renowned contemporary artist

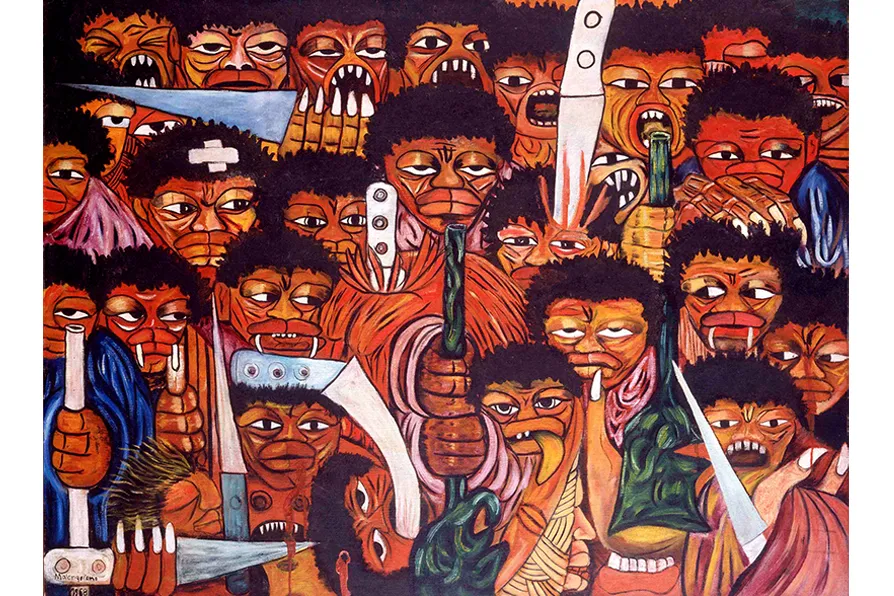

Malangatana Ngwenya, 25th of September II, (1968). Images like this, made after Malangatana’s release from prison directly reference FRELIMO’s challenge to colonialism. The date marks the 4th anniversary of the start of the armed struggle. [Pic: FMS/FMVN]

Malangatana Ngwenya, 25th of September II, (1968). Images like this, made after Malangatana’s release from prison directly reference FRELIMO’s challenge to colonialism. The date marks the 4th anniversary of the start of the armed struggle. [Pic: FMS/FMVN]

Malangatana: Eye of the Crocodile

Richard Gray, Galda Verlag Berlin, £172

![Judgement of Frelimo Militants, 1966. Images like this, made after Malangatana’s release from prison directly reference FRELIMO’s challenge to colonialism [Pic: FMVN/Courtesy of Richard Gray]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2025-10/Fig%209.%20Julgamento%20dos%20Militantes%20da%20FRELIMO.jpg.webp?itok=cxmqUD5X)

AFRICAN art has, in past centuries, been largely ignored by Europeans and/or dismissed as “primitive” and only worthy of inclusion in collections of colonial plunder in anthropological museums.

It was only when 20th century artists like Picasso, Matisse and Braque found inspiration in it, and particularly its sculpture — with its bold, simplified forms and the concept of a spiritual connection and a new way of seeing and representing the world — that it began to attract attention as valid art to be set alongside that of European and Asian origin. Its stylised forms, emotional depth and fragmented shapes contributed significantly to the development of modern art movements like Cubism.

The Mozambiquan artist Malangatana was one of the foremost representatives of 20th century African art, although his genius was not widely recognised outside Mozambique. His work is deeply rooted in his experience as a member of the Ronga ethnic group from southern Mozambique, but it transcends that narrow base to represent the lives and struggles of a whole nation.

The author Richard Gray has worked for many years to set that record straight. His book is the first to document the life and work of a great artist. In his foreword, the artist and curator Chris Spring writes: “This is a very remarkable book in many respects, not least because of Richard Gray’s long personal relationship with Malangatana… This gives the text an air of profound authenticity, revealing the artist’s work from Malangatana’s own perspective while at the same time addressing global issues of decolonization and racism.”

Gray first arrived in Mozambique in 1977 when he worked as a “co-operante internacionalista.” This book is based, I assume, on his PhD thesis on Malangatana. It is the first in-depth and meticulously researched biography in English of the artist’s life and art.

For a general reader it is perhaps too detailed but certainly provides a fuller understanding of Malangatana’s relevance in his home country and of the contribution he has made with his art to the liberation of Mozambique.

During the early stages of his career, like so many of his fellow African artists Malangatana was seen by the cultural elite in the Western world as a “self-taught naif” but in actual fact he had attended colonial Mozambique’s elite art school, the Nucleo de Arte, where he received a formal art training and learned from other artists.

![Punishment Cell, 1965 [Pic: The Museum of Modern Art, New York]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2025-10/Fig%206.%20Cela%20Disciplinar%20%28PIDE%20Punishment%20Cell%29%20scala_0166494.jpg.webp?itok=Pn-HP642)

His art bears a ressemblance to that of the German expressionist Emil Nolde in its vibrant colours and simplified human forms, as well as its early treatment of religious themes. Nolde, and the painters of Die Brucke wanted to follow Van Gogh and create a new “folk art,” and this template provided Malangatana with a basic vocabulary to establish just such an artistic vocabulary in his native Mozambique.

But the ressemblance stops there. If Nolde’s primitivist mission led him to become an enthusiastic member of the Nazi Party, Malangatana’s fluid, simplified line and bold colours undo the racism to accompany him through the anti-colonialist struggle of his early years and then into historical documentation of his participation in Frelimo (the Mozambique Liberation Front), taking in such remarkable icons of political solidarity as Going to the Independence War and Saying Goodbye (1964), his prison sketchbook (Punishment Cell, 1965), and even his depiction of a political trial, Judgement of Frelimo Militants (1966).

Malangatana’s canvases are characterised by their vibrant colours, often crammed with numerous figures, as if the frame can’t contain the forces portrayed within it. He also executed delicate black-and-white pen and ink drawings. His early sketches from prison and his diary entries reveal the harsh colonial subjugation of political prisoners.

In his nude paintings one can clearly see a direct link to Picasso and the Cubists. One extraordinary painting, Prisoner’s Dream (1966), fuses the sensuality that is essential to his art with the political: a male prisoner dreams of the woman he misses, and the canvas is populated with a similar defiance: prisoners who recall their murdered comrades.

The book is copiously illustrated with the artist’s works and photos of his family. Gray’s friendship with him, began in 1978, three years after independence and helped him, he writes, to comprehend “his viewpoint on the turbulent events of this half-century.”

Gray writes: “I had two key questions. How did Malangatana situate himself in relation to the histories and expectations which he encountered? How did he act in the face of them? I write of these factors in the plural because several sets of histories and expectations confronted him. First were those of the Rongas (his ethnic roots), second, those of the Portuguese colonial system and third, those of Frelimo, the national liberation movement, which became Mozambique’s ruling party at independence.”

The book highlights such pivotal moments in Malangatana’s life and the recent history of the country, including the post-independence struggle between the South African backed Renamo counter-revolutionaries and Frelimo.

![“Man and Nature”, a mural painted between 1977 and 1979, is on the premises of the Museum of Natural History in Maputo, and restored in 2020 [Pic: FMVN/Courtesy of Richard Gray]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2025-10/Fig%205.%20Nat%20Hist%20Museum%20Mural.%20shutterstock_editorial_8609641d.jpg.webp?itok=8kExvDOb)

Of particular note is Malangatana’s dedication to mural art, much like that of Diego Rivera in Mexico. These popular works, situated in towns and villages celebrate the intimate details of the working lives of men and women, and the story of the construction of one such mural is beautifully told in Adrian Pennink’s Arena documentary Homelands, which can be viewed on YouTube.

Most of Malangatana’s paintings and drawings are held in his personal collection, based in Maputo. The publication of this book about him and his art celebrates 50 years of Mozambican independence from Portuguese colonialism.

Most previous writers have ignored the political aspects of Malangatana’s works, but Gray pays them due attention, and how his abhorrence of the effects of the war between Frelimo and Renamo informed his artistic output and led him to campaign for peace. Towards the end of his life, he became a roving cultural ambassador for Mozambique, accompanying his works and those of other Mozambican artists to destinations on both sides of the cold war ideological divide.

The title of the book makes reference to the Ronga aphorism: “The strength of the crocodile is in the water.” Malangatana’s persistent loyalty to his homeland and its own evolving culture is the water he never left, and the aphorism applies equally apply to the artist’s life and work, as well as to the history of a country under colonialism, perceived from within.

In his second round-up, EWAN CAMERON picks excellent solo shows that deal with Scottishness, Englishness and race as highlights

ANGUS REID recommends a visit to an outstanding gathering of national and international folk musicians in the northern archipelago

Badenoch under pressure to sack shadow justice secretary