SUE TURNER is fascinated by a book that researches who the largely immigrant workforce were that built the Empire State

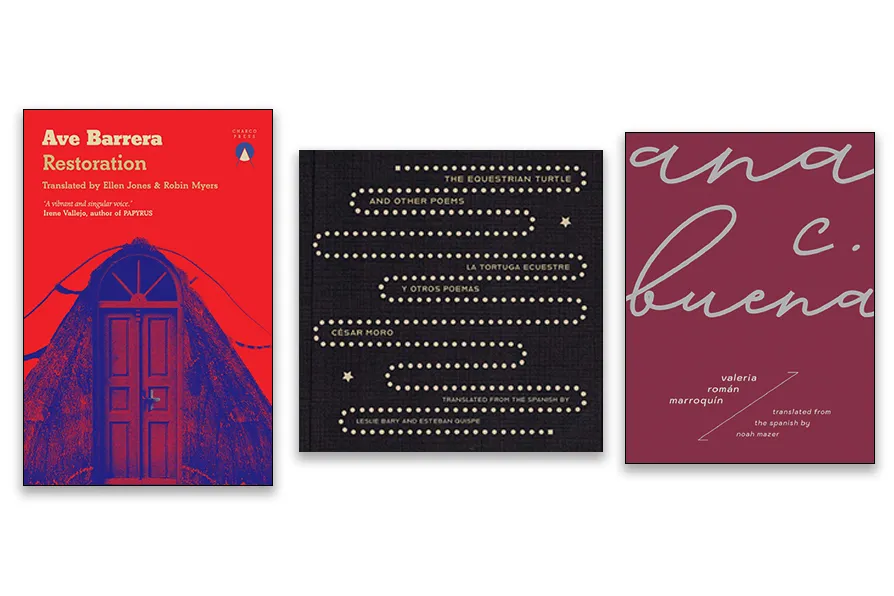

A ghost story by Mexican Ave Barrera, a Surrealist poetry collection by Peruvian Cesar Moro, and a manifesto-poem on women’s labour and capitalist havoc by Peruvian Valeria Roman Marroquin

“I REMEMBER the first time Zuri showed me the house. He took my hand as we crossed the street, stopped on the corner, then said suddenly: This is it.” So begins Ave Barrera’s masterful ghost story Restoration (Charco Press, £11.99), translated by Ellen Jones and Robin Myers.

Barrera’s Mexico City is no place for faint hearts: Jasmina, an artist, is roped in by her toxic boyfriend to restore his crumbling family mansion. But the house is less home and more tomb, thick with the detritus of history and the weight of women’s silenced lives.

“We all know what happens in stories to women who open doors that men have forbidden them from opening,” Jasmina warns, and sure enough, what she uncovers is not ectoplasm but patriarchy: a lineage of male violence haunting the very walls. The house becomes a metaphor for a society where misogyny seeps into the foundations, and restoration is never simply a matter of plaster and paint.

Like the building itself, the narrative fractures and splinters, refusing neat closure. It’s a ghost story where the ghost is capitalism’s oldest accomplice: patriarchy.

If Barrera’s ghosts live in bricks and mortar, Cesar Moro’s are lodged in flesh and dream. The Equestrian Turtle and Other Poems (Cardboard House Press, £15), translated by Leslie Bary and Esteban Quispe, resurrects the dazzling queer surrealism of one of Peru’s most original poets. Moro’s turtle, slow but saddled, is a creature of contradiction: absurd, erotic, defiant.

Written in the 1930s, his poems pulse with homoerotic desire, bodily metamorphosis, and images that gallop off logic’s leash. “I raise a statue made of purest mud/ of clay of my blood/ of lucid shade of untouched hunger/ of endless panting.”

Moro’s surrealism is not escapism — it’s insurgency, a refusal of bourgeois reality in favour of a delirious, bodily truth. His work reminds us that queerness and surrealism share a common project: to make desire ungovernable.

Desire, however, is harder to sustain when hunger gnaws at the belly. That is the terrain of Valeria Roman Marroquin’s ana c. buena (Cardboard House Press, £12), a manifesto-poem about women’s labour under capitalism.

Ana, a domestic worker, chops onions, scrubs tables, and disappears into the fabric of other people’s homes. “ana, think about the labour that fastens you:/ crushing peppers,/ chopping onions,/ settling the shrinking stomach/ — other people’s stomachs —.”

Roman lays bare the everyday violence of “miracle” economies built on invisible, feminised labour. Ana is ghosted not by death but by work itself, her body worn into transparency. In Roman’s hands, the kitchen becomes as haunted as Barrera’s mansion, and just as claustrophobic.

What ties these three extraordinary books together is the persistence of ghosts — not the gothic kind, but the kind conjured by patriarchy, hunger and capitalism’s knack for making people disappear into its walls. Between them, they remind us that the supernatural is unnecessary: our world is already full of spectres. And as Marx said, some of them still haunt Europe — and beyond.

LEO BOIX introduces a bold novel by Mapuche writer Daniela Catrileo, a raw memoir from Cuban-Russian author Anna Lidia Vega Serova, and powerful poetry by Mexican Juana Adcock

A novel by Argentinian Jorge Consiglio, a personal dictionary by Uruguayan Ida Vitale, and poetry by Mexican Homero Aridjis