CHRISTOPHE DOMEC speaks to CHRIS SMALLS, who helped set up the Amazon Labor Union, on how weak leadership debilitates union activism and dilutes their purpose

The Congolese independence leader’s uncompromising speech about 80 years of European colonial brutality and injustice went round the world in 1960, and within months, he had been executed by Belgian and CIA-backed forces, writes KEITH BARLOW

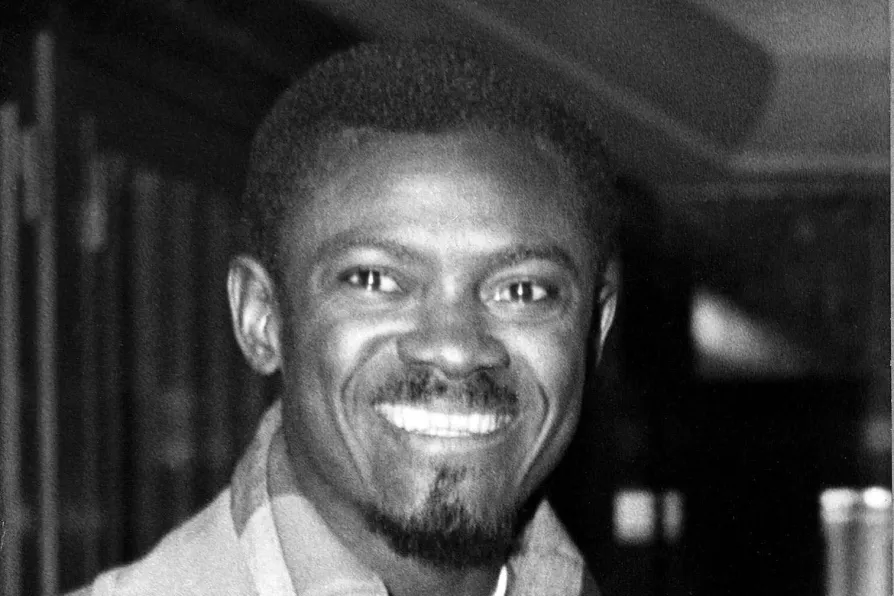

Patrice Lumumba in Leopoldville, which later became Kinshasa, 1960

Patrice Lumumba in Leopoldville, which later became Kinshasa, 1960

YESTERDAY marked the centenary of the birth of the Congolese independence leader, Patrice Emery Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and icon of the anti-colonial struggle in Africa.

Alongside independence leaders like Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and the anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela, Lumumba symbolises the struggle against colonial domination, oppression and racism at the height of the cold war.

The DRC had originally become a Belgian colony when King Leopold II seized land across central Africa in 1885, making it his personal property. This became known as the Congo Free State. Leopold’s alleged goal of developing the country was, in practice, to plunder its resources. Its people suffered the most atrocious forms of deprivation and brutality. Malnutrition, disease and torture — including the amputation of hands and feet — became the order of the day. Resistance to the king’s rule was not tolerated.

In 1908, international pressure forced Leopold to turn the country over to the Belgian government, and the territory was renamed the Belgian Congo. This in no way changed the plight of its population. Resistance to foreign domination continued.

Through the 1950s, demands for independence from colonial rule swept throughout much of the world, including Africa and the Belgian Congo. Out of this came, in 1958, the founding of the Congolese National Movement, which was led by Lumumba till his execution in 1961.

On January 4 1959, thousands demonstrated for independence in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), a mobilisation followed by a two-day rampage by Belgian security forces. Three hundred demonstrators were killed.

Yet resistance to Belgian rule quickly grew to the point where Belgium realised a new response was required. On May 22 1960, national elections took place for the first time. Belgian hopes for a compliant government were not fulfilled.

The alliance around Lumumba won 71 of the 137 seats in parliament. However, in the Senate, 23 seats out of the 84 were reserved for local leaders, generally supporters of the colonial authorities and Lumumba’s remained two seats short of a majority. Consequently, Lumumba was forced to form a coalition with his Belgian-backed rival, Joseph Kasa-Vubu. Kasa-Vubu became president, and Lumumba prime minister.

Independence was set for June 30 1960. That day, the Belgian Congo became the Democratic Republic of Congo. The then Belgian king, Baudouin, in his speech at the Ceremony of the Proclamation of the Congo’s Independence in Kinshasa, sought to glorify what his great-grandfather did for the Congo.

He mentioned various economic projects and totally disregarded the years of suffering by the native Congolese. He praised his great-grandfather “as a bringer of civilisation.” For Lumumba, those 80 years could not be ignored.

The new prime minister said: “Although this independence of the Congo is being proclaimed today by agreement with Belgium, an amicable country, with which we are on equal terms, no Congolese will ever forget that independence was won in struggle, a persevering and inspired struggle carried on from day to day, a struggle in which we were undaunted by privation or suffering and stinted neither strength nor blood … It was filled with tears, fire and blood. That was our lot for the 80 years of colonial rule.

“We have experienced forced labour in exchange for pay that did not allow us to satisfy our hunger, to clothe ourselves, to have decent lodgings or to bring up our children as dearly loved ones. Morning, noon and night we were subjected to jeers, insults and blows because we were ‘negroes.’ Who will ever forget that the black was addressed as ‘tu,’ not because he was a friend, but because the polite ‘vous’ was reserved for the white man?

“We have seen our lands seized in the name of ostensibly just laws, which gave recognition to the right of might. We have not forgotten that the law was never the same for the white and the black, that it was lenient to the ones, and cruel and inhuman to the others. We have experienced the atrocious sufferings … exiled from our native land: our lot was worse than death itself …

“Who will ever forget the shootings which killed so many of our brothers, or the cells into which were thrown those who no longer wished to submit to the regime of injustice, oppression and exploitation used by the colonialists as a tool of their domination?”

His speech went round the world. He spoke for the millions engaged in the struggle against colonial rule and oppression. His key message was that independence must also mean former colonial powers coming to terms with how the peoples in their colonial territories were ruled — not just colonial authorities being replaced by pliable governments defending the colonisers’ interests.

However, within months, Lumumba had been murdered. His fate must be seen in the context of the cold war.

The new president Kasa-Vubu plotted with Belgium and the CIA to dismiss him. Almost immediately, the DRC was faced with mutiny in the army. Just 12 days after independence, on July 11 1960, the president of the mineral-rich Congolese province of Katanga, Moise Tshombe, an opponent of Lumumba, announced that Katanga was going to break away.

Although his move was backed by foreign mining concerns, his regime did not secure international recognition, not even from Belgium. However, Belgian troops, ostensibly sent to protect Belgian nationals, were used to prop up Tshombe, ensure continued access to the mineral resources and to set up a puppet regime as part of the plot to depose Lumumba.

On September 5 1960, Kasa-Vubu dismissed Lumumba and a number of his closest ministers. Lumumba sought to resist dismissal by arguing that the procedures for doing this did not comply with the country’s new constitution and sought to dismiss the president. The DRC now had two parallel governments.

On September 14, the Congolese colonel Mobutu launched a military intervention to back Kasa-Vubu. Lumumba was placed under house arrest. He escaped in an attempt to get to another part of the country but fell directly into the hands of Mobutu.

On January 17 1961, Lumumba and two companions, Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, were flown to Katanga. During the flight, they were beaten by soldiers and, upon arrival, subject to further beatings by Belgian and Congolese officers. They were then executed by a Katangan firing squad under Belgian supervision and their bodies thrown into shallow graves.

Later, a Katangan government official ordered that the bodies “disappear.” A Belgian police officer led a group to search the graves, hacked the bodies to pieces and dissolved what they could in sulphuric acid. Anything that remained was to be burned.

All that survived from Lumumba was a tooth, which was taken as a souvenir by a Belgian police officer and later returned to Lumumba’s family on a court order. It was placed in a coffin and transferred into a specially built mausoleum in his memory in Kinshasa.

Only in 2002, after an 18-month parliamentary inquiry, did Belgium formally apologise for its role in the killing of Lumumba. This was made by the then Belgian foreign minister, Louis Michel, in a parliamentary debate on this inquiry. Of course, it failed to link any direct involvement of the Belgian government in this murder, but one can conclude that it knew what was going on and did nothing to prevent it.

Today, the name of Lumumba is honoured around the world and not only in Africa. In Leipzig, where I live, there is still a street named after him, Lumumbastrasse. A memorial in his memory dates back to GDR times.

Perhaps the most fitting memory of Lumumba is to be found in Moscow through the naming of a university after him (which I briefly visited when I was in Moscow in 1982). This university had already been opened in 1960 for the purpose of providing students from developing countries with a university education. It was named in his memory just five days after he was killed.

The charter emerged from a profoundly democratic process where people across South Africa answered ‘What kind of country do we want?’ — but imperial backlash and neoliberal compromise deferred its deepest transformations, argues RONNIE KASRILS

PRABHAT PATNAIK details the epochal shift of political power from Western neocolonialists to the people