DENNIS BROE searches the literary canon to explore why a duplicitous, lying, cheating, conning US businessman is accepted as Scammer-in-Chief

ALEX DITTRICH hitches a ride on a jaw-dropping tour of the parasite world

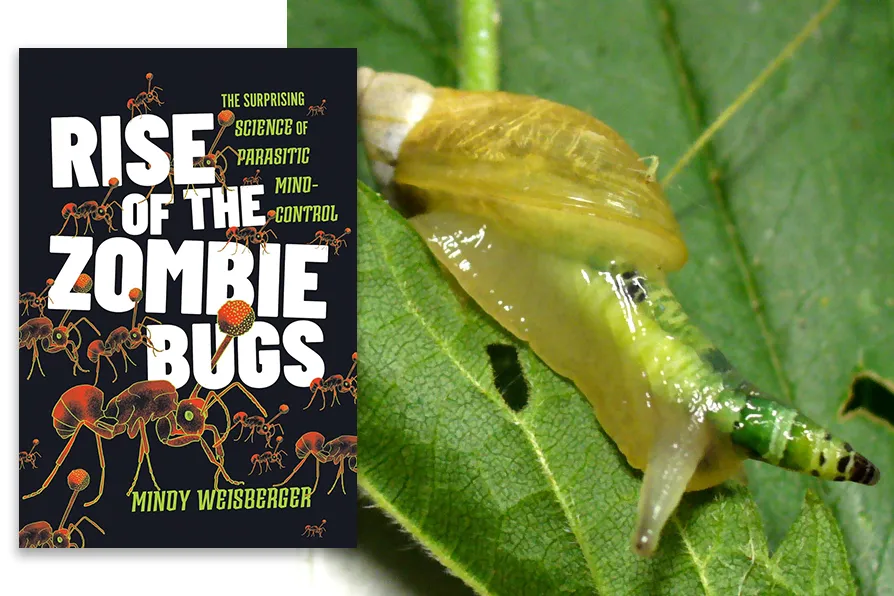

Succinea putris (snail) with the parasitic trematode Leucochloridium paradoxum inside its left tentacle. [Pic: Thomas Hahmann/CC]

Succinea putris (snail) with the parasitic trematode Leucochloridium paradoxum inside its left tentacle. [Pic: Thomas Hahmann/CC]

Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control

Mindy Weisberger, Johns Hopkins University Press, £25

RISE OF THE ZOMBIE BUGS is a non-fiction book that borrows from popular culture to make one of the most complex and grisly interactions in the animal kingdom accessible to the reader.

From fungi and viruses that infect the brains of insects, to parasites that burst through the abdominal cavities of their unsuspecting hosts, Weisberger shows readers a gruesomely fascinating world.

Weisberger’s definition of a zombie bug is an insect that has become host to a parasite. The parasite modifies its host’s behaviour for its own means. She affectionately refers to these parasites as “zombifiers.” This zombification can make the host more susceptible to conditions that enable that parasite to complete its lifecycle or spread.

The author takes the reader through a taxonomic feast of invertebrates and their parasites. The idea of “host-altered behaviour” is particularly interesting here, as it shows the ends that parasites go to to complete their lifecycle and reproduce.

For example Leucochloridium, a flatworm that turns the eyes of snails vivid colours and patterns, which makes them more susceptible to bird predation. The flatworm also makes the snail stay out in the open. Once eaten by a bird, the flatworm can complete its life cycle in the bird’s gut. And Weisberger helps the reader understand some of the complex processes that underpin this phenomenon. For example, how these parasites hijack the host’s nervous system and cause unusual behaviour.

There are parasitic flies that disrupt the natural foraging behaviour of ants. After the fly lays eggs in the ant’s thorax, the larvae eventually migrate to the ant’s head, making it fall off. There’s also the cordyceps fungi that infects the brains of many insect species and makes them move to a better location for the fungi, such as the ends of tree branches or the tips of grass stems. A location normally treacherous to the insect – but ideal for the fungi to spread its spores. Once there, a fruiting mushroom sprouts from the insect’s head.

Parasites are all around us. Weisberger reassures us that, although the grisly and fantastical world of fiction is not far removed from what we see in nature, the processes she describes in the book are natural. And indeed necessary for a healthy planet, playing a crucial role in controlling and halting pest invasions. In the insect world, they are one of the most abundant natural controls on populations of pest insects.

Although naturally occurring populations of these parasites are not more likely to attack invasive species than native ones, we have however used them to our advantage in exploiting their behaviour to protect our crops. For example, the parasitic wasps I mentioned before are key for controlling populations of beetle pests in fruiting crops.

However, the book does end on a note of caution. The author writes a worrying footnote on rabies and Toxoplasma gondii, and the ability of both to not only cause serious harm to us but to even alter our behaviour.

Toxoplasma gondii is a single-cell parasite that causes an illness called toxoplasmosis in humans. You can catch it from cat faeces, or from eating infected meat. It is one of the most common parasitic infections of humans and other warm-blooded animals. It doesn’t make most adults seriously ill but it can cause blindness and developmental disorders in children infected as a foetus and cause life-threatening illness in immunocompromised people.

Toxoplasmosis has been linked to rage and suicidal behaviour in humans. Although one third of people are estimated to have been exposed to toxoplasmosis, there is still much we don’t understand about it.

Rise of the Zombie Bugs is a fun read that would appeal to a wide range of audiences, whether you work in science and education or simply want to expand your understanding of the natural world.

Alex Dittrich is Senior Lecturer in Zoology, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

![]()

JULIA THOMAS unpicks the mental processes that explain why book-to-film adaptations so often disappoint

JOSEPHINE BARBARO welcomes a diverse anthology of experiences by autistic women that amounts to a resounding chorus, demanding to be heard

MANJEET RIDON relishes a novel that explores the guilty repressions – and sexual awakenings – of a post-war Dutch bourgeois family

ALASTAIR BONNETT reports on the paradoxes of populist attitudes towards protection of the natural world