MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review "Wuthering Heights", Little Amelie or the Character of Rain, Crime 101, and Stitch Head

SUE TURNER welcomes a thoughtful, engaging book that lays bare the economic realities of global waste management

Waste Wars — Dirty Deals, International Rivalries and the Scandalous Afterlife of Rubbish

Alexander Clapp, John Murray, £25

IT has always been thus; dangerous, filthy and smelly trades have been conducted downwind or out of sight of more salubrious neighbourhoods — dyeworks, tanneries and slaughterhouses spring to mind.

Today waste management fits into this list. Instead of “salubrious neighbourhoods” read affluent nations of the global north and for “downwind and out of sight” read countries of the global South.

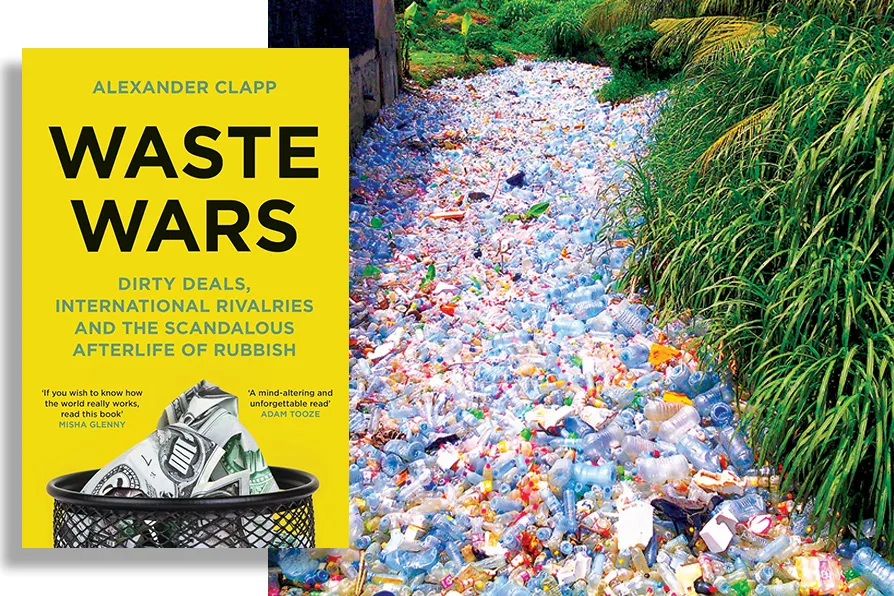

With the increasing use of plastics after the WWII, waste disposal has become a trillion dollar industry involving billions of tons of rubbish which is dumped both legally and illegally on developing countries, creating devastated landscapes, polluted waterways and stunted, ruined lives.

Raw materials such as gold, copper and lithium are extracted from developing countries to be manufactured into high-tech goods in rich nations, and when these goods become obsolete they are returned to poorer countries for the usable materials to be extracted again for resale, while any plastic components are dumped or burnt in the open.

Countries that believed they had freed themselves from colonialism have become dustbins for northern over-consumerism. The Netherlands, once Indonesia’s colonial master, is now its greatest supplier of plastic waste. In 2000 California decreed that in order to maintain its environmental credentials 50 per cent of its discarded plastic must leave the state making it one of the world’s leading international exporters of rubbish.

And of the world’s 50 largest dumpsites, 48 are in developing nations.

In his 1988 address to the UN Robert Mugabe said: “Africa has enough problems of her own without becoming the garbage bin of the wealthy northern nations. It is unfair that the poorest nations should … suffer the worst effects of a programme they do not share.”

How the world has arrived in this situation which Clapp calls “garbage imperialism” is the subject of this book, and the result of two years’ global research.

He charts the rise of consumerism and the use of plastics by referring to Vance Packard’s famous book The Hidden Persuaders (IG Publishing, 2007) and the lesser-known The Waste Makers (IG Publishing, 2011) which argued that Americans were being encouraged to overconsume, and particularly products with built-in obsolescence, leading to a throwaway society which today has 1.5 billion plastic cups and 220 million aluminium cans discarded daily worldwide. Every minute one million plastic bottles are thrown away and one refuse truckful of plastic enters the sea.

Clapp moves along at pace explaining how and why rubbish began to be exported for processing, emphasising the lack of adherence to national and international laws.

He writes that due to improved environmental laws in the US in the 1980s, the price of burying a ton of asbestos rose from $15 to $250, while the cost of disposal in some African states could be $3. Some local elites in developing countries were bribed to accept toxic waste with promises of schools, weapons or a stake in the waste operations although these promises often failed to materialise.

The European Anti-Fraud Office estimates that illegal waste trafficking is more lucrative than the trafficking of humans. Many operators are moving from the drugs or weapons trade into international waste disposal as the risks are lower and the financial rewards are greater.

Clapp balances his analysis of the processes and problems with description of the daily working lives and living conditions of the labourers. Many have left agricultural villages to seek a better living only to find themselves in unregulated work conditions, and falling prey to cancers and respiratory diseases.

Some of Clapp’s most harrowing writing is found in his description of the dangerous, back-breaking work in the ship-breaking yards of Bangladesh, Pakistan and India.

Equally shocking is his exposé of the handling of plastics in Java which are used as fuel in tofu factories: one room family businesses which can’t burn the plastic at high enough temperatures to eliminate the toxins which end up baked into the tofu.

Clapp has produced a thoughtful, engaging book which has all the elements of investigative journalism — a fascinating if troubling read.

From summit to summit, imperialist companies and governments cut, delay or water down their commitments, warn the Communist Parties of Britain, France, Portugal and Spain and the Workers Party of Belgium in a joint statement on Cop30

One of the major criticisms of China’s breakneck development in recent decades has been the impact on nature — returning after 15 years away, BEN CHACKO assessed whether the government’s recent turn to environmentalism has yielded results

RON JACOBS salutes a magnificent narrative that demonstrates how the war replaced European colonialism with US imperialism and Soviet power