The proxy war in Ukraine is heading to a denouement with the US and Russia dividing the spoils while the European powers stand bewildered by events they have been wilfully blind to, says KEVIN OVENDEN

The working week doesn’t have to look the way it does today

JAMES MEADWAY reminds us that the standard eight-hour day, five days a week is only a relatively recent invention

THE four-day week trials, overseen by the think tank Autonomy, working with researchers from Oxford, Cambridge and Boston universities, came to an end last week.

Over 80 companies signed up to take part, promising to reduce their typical working hours by a day, but keep pay the same.

There’ll be a full report due out in February, but early results sound encouraging, with businesses reporting both happier staff and improvements in their productivity.

More from this author

Already the extremism of the new Argentinian president’s administration is being watered down in the face of reality – but now the Chinese central bank has cut funding it could be in serious trouble, writes JAMES MEADWAY

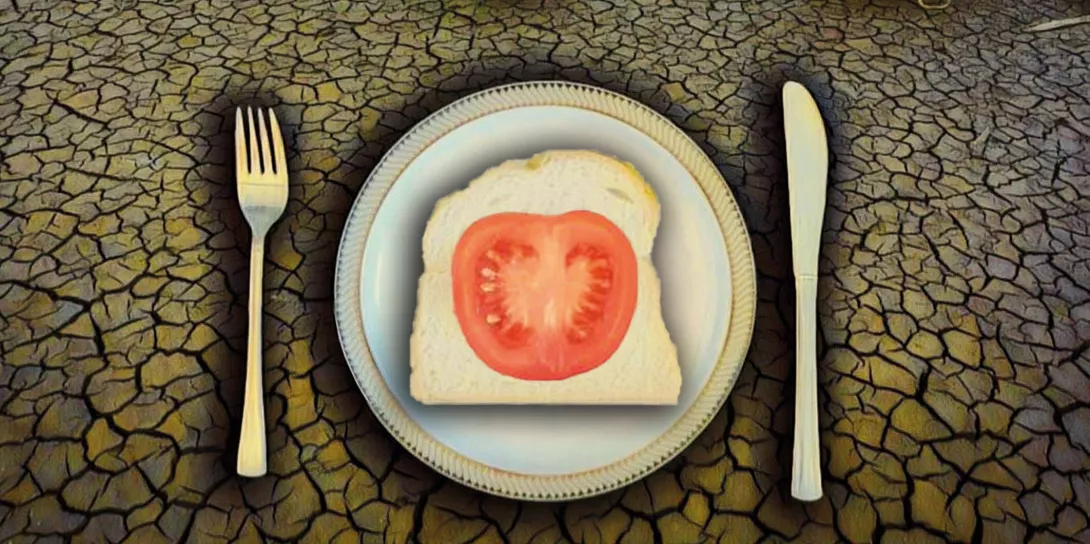

JAMES MEADWAY looks at the multiple emerging crises, most linked to climate change, that will lead to price rises for consumers and bumper profits for big business. The solutions, however, are simple

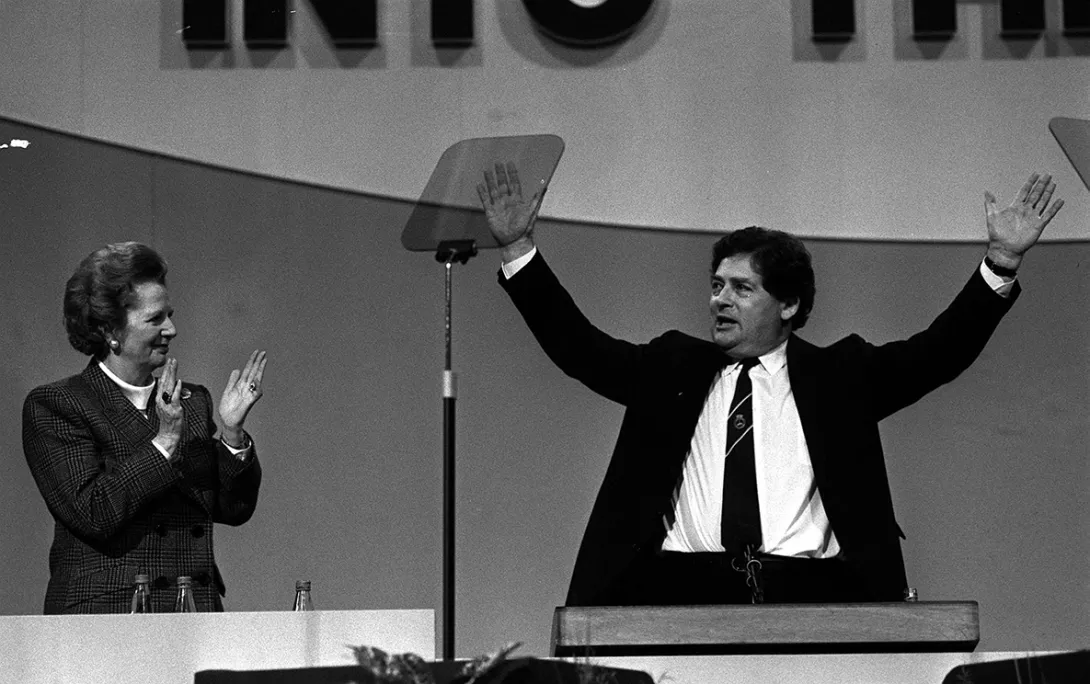

An early adherent of free-market fundamentalism, at Thatcher's side throughout her most damaging years, Lawson attacked our unions, industry and the very fabric of our society, writes JAMES MEADWAY

The Bank of England has been swinging its interest rate bludgeon for the last year, and the wreckage is starting to pile up, warns JAMES MEADWAY

Similar stories

Socialist historian KEITH FLETT traces the parallel evolution of violent loyalist rampages and the workers' movement's peaceful democratic crowds, highlighting the stark contrast between recent far-right thuggery and mass Gaza protests

ANGUS REID speaks to Angus Farquhar about the political roots of his work with communities from the 1980s to the present day, and why he is inviting everyone to plant seeds in Glasgow Necropolis

The Star publishes the Karl Marx Graveside Oration delivered by Lord JOHN HENDY KC at Highgate Cemetery on Sunday, on behalf of the Marx Memorial Library