CHRISTOPHE DOMEC speaks to CHRIS SMALLS, who helped set up the Amazon Labor Union, on how weak leadership debilitates union activism and dilutes their purpose

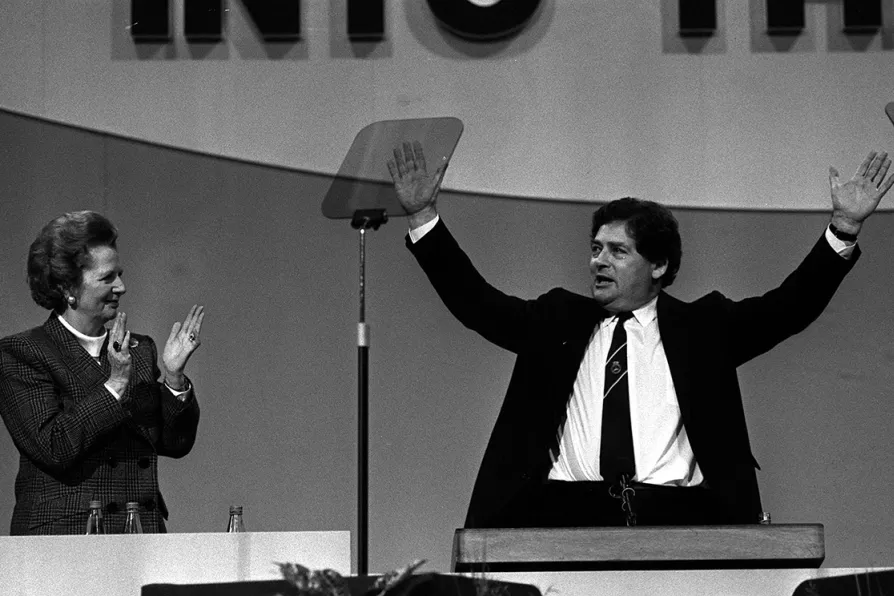

Nigel Lawson, applauded by then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, at the end of his speech during the Conservative Party's annual conference in 1988

Nigel Lawson, applauded by then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, at the end of his speech during the Conservative Party's annual conference in 1988

THE former Tory Party chancellor Nigel Lawson, who died last week aged 91, had become better known in his later years as an indefatigable champion of the cause of climate change denial.

His efforts to minimise perceptions of the damage of greenhouse gas emissions, and forestall action on decarbonisation, played their own small part in condemning future generations to lives that will be harder and more squalid than they ever needed to be.

But it was as the primary architect of Britain’s free-market turn, and Margaret Thatcher’s sometime right-hand man, that Lawson can claim his true legacy.

Four decades on, the Wapping dispute stands as both a heroic act of resistance and a decisive moment in the long campaign to break trade union power. Lord JOHN HENDY KC looks back on the events of 1986

DOUG NICHOLLS argues that to promote the aspirations for peace and socialism that defeated the Nazis 80 years ago we must today detach ourselves from the United States and assert the importance of national self-determination and peaceful coexistence

Hundreds of protesters rally outside global energy summit in London