RITA DI SANTO draws attention to a new film that features Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn, and their personal experience of media misrepresentation

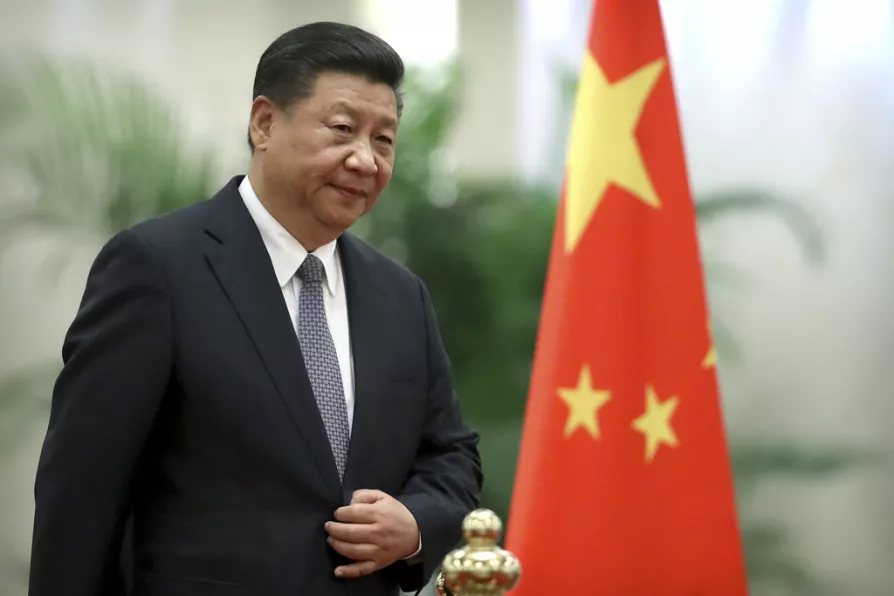

Contentious conclusions on Xi Jinping

An otherwise valuable overview of the Chinese leader's thinking is marred by liberal bias, says KENNY COYLE

Strategist: Xi Jinping

Strategist: Xi Jinping

Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping

by Francois Bougon

(Hurst £12.99)

ONE of the most powerful politicians on the planet, Chinese leader Xi Jinping still remains a puzzle to many Western observers.

Taking the helm at a crucial point in China’s development path as it rises to middle-income levels, Xi’s focus on advancing his country’s modernisation, while firmly rejecting Western economic and political models, has provoked considerable panic among Atlanticist liberals and corporate conservatives alike.

Similar stories

RON JACOBS welcomes the long overdue translation of an epic work that chronicles resistance to fascism during WWII

NICK WRIGHT delicately unpicks the eloquent writings on art of an intellectual pessimist who wears his Marxism lightly

CARLOS MARTINEZ welcomes the publication of the writings of the great Palestinian author, political theorist and spokesman for the PFLP