John Wojcik pays tribute to a black US activist who spent six decades at the forefront of struggles for voting rights, economic justice and peace – reshaping US politics and inspiring movements worldwide

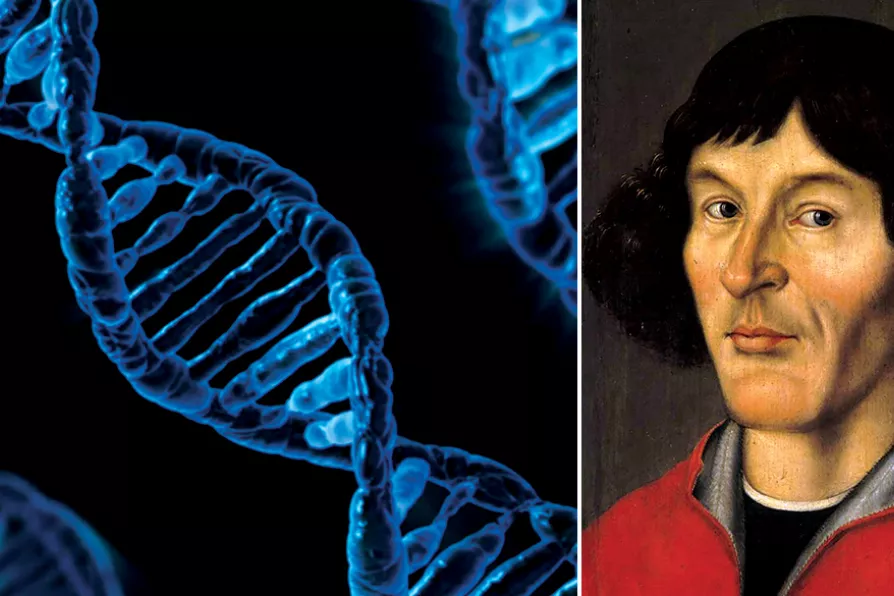

PARADIGM SHIFTS: (L to R) The human DNA model takes on a double helix shape, 2016; Portrait Nicolaus Copernicus Torun Town Hall, 1580, unknown artist

PARADIGM SHIFTS: (L to R) The human DNA model takes on a double helix shape, 2016; Portrait Nicolaus Copernicus Torun Town Hall, 1580, unknown artist

IN 1962 the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn published the book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

In it he claimed that science progressed through a series of revolutions in scientific knowledge for which he coined the term “paradigm shifts.”

These paradigm shifts were radical new ideas and knowledge that subverted the previous understanding in a field of science and set it on an entirely new path.

JOHN GREEN’s palate is tickled by useful information leavened by amusing and unusual anecdotes, incidental gossip and scare stories

Neutrinos are so abundant that 400 trillion pass through your body every second. ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT explain how scientists are seeking to know more about them

A maverick’s self-inflicted snake bites could unlock breakthrough treatments – but they also reveal deeper tensions between noble scientific curiosity and cold corporate callousness, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

Science has always been mixed up with money and power, but as a decorative facade for megayachts, it risks leaving reality behind altogether, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT