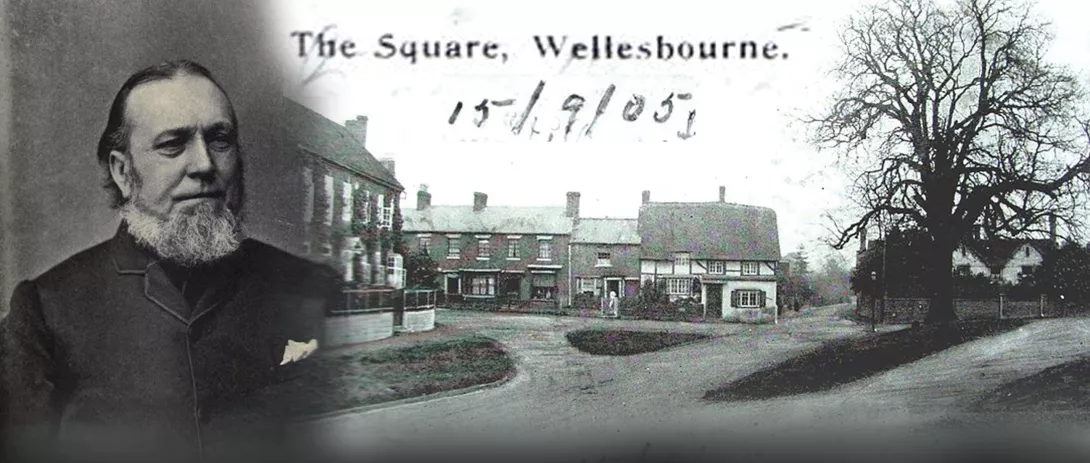

THIS week marks some significant celebrations of rural class struggle. The wonderful rally at Burston marking “the longest strike in history” — the astonishing Burston School Strike from 1914 to 1939 — is to be followed by the Joseph Arch Walk in Warwickshire.

The Burston strike was led by the wonderful Kitty and Tom Higdon. Perhaps less well-known than the strike is Tom’s role as secretary of the Norfolk County Agricultural Workers Union up until 1938.

Nowadays our image of rural Britain is largely one of Countryfile and bucolic TV advertisements. It was Raymond Williams in his marvellous book The Country and the City who debunked the notion of rural life as simple, natural, and unadulterated, leaving us with an image of country life as if living in some kind of golden age.

This is, according to Williams, “a myth functioning as a memory” that dissimulates class conflict, enmity, and animosity that had been present in rural Britain since the 16th century.

Higdon was in the front rank of this rural class struggle. The NUAW (motto: “We sow the seed that feeds the world”) was the successor to Joseph Arch’s National Agricultural Labourers’ Union, and it principally fought for improved wages for agricultural workers — most notably, in the great strike of 1923 which reversed the decline in agricultural wages after the first world war. The union was based in Norfolk but attracted support from around the country.