A survey circulated by a far-right-linked student group has sparked outrage, with educators, historians and veterans warning that profiling teachers for their political views echoes fascist-era practices. FEDERICA ADRIANI reports

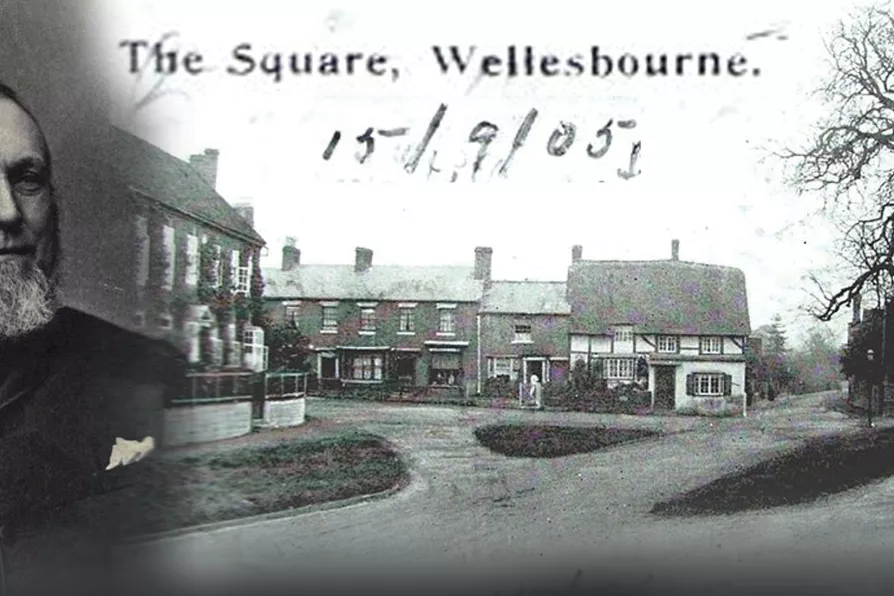

WORKING-CLASS HISTORY: A postcard photo from around 1905 of the original Wellesbourne Tree where Joseph Arch (left) first addressed a crowd of agricultural labourers in 1872

WORKING-CLASS HISTORY: A postcard photo from around 1905 of the original Wellesbourne Tree where Joseph Arch (left) first addressed a crowd of agricultural labourers in 1872

JOSEPH Arch Day again takes place in the Warwickshire villages of Wellesbourne and Barford on September 7. This year Professor James Crossley will give the guest lecture at the Joseph Arch Commemoration. I took the chance to ask him a few questions.

Nick Matthews: I loved your book, The Spectres of John Ball. Great read and tremendous scholarship. Restoring Ball as a central figure in English history. One of the things that comes out of that work is the way historical characters and events are commemorated by different generations with their meaning often changing.

When we restarted marking the life of Joseph Arch it was 150 years after the legendary meeting outside the Stag’s Head in Wellsbourne, Warwickshire, which led to the formation of the National Union of Agricultural Workers.

BEN CHACKO welcomes a masterful analysis that puts class struggle back at the heart of our understanding of China’s revolution