RITA DI SANTO draws attention to a new film that features Ken Loach and Jeremy Corbyn, and their personal experience of media misrepresentation

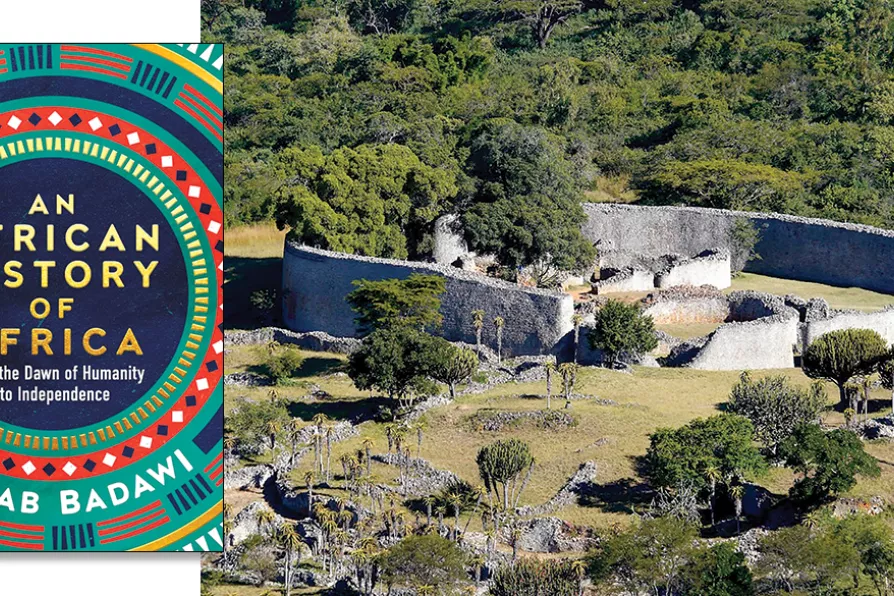

ANCIENT SPLENDOUR: The Great Zimbabwe dates back to the Gokomere people, an eastern Bantu subgroup, which lived in the area from around 200AD and flourished from 500AD to about 800AD. The stone city spans an area of 7.22 square kilometres (2.79 sq mi) and could have housed up to 18,000 people at its peak. It is suggested that Zimbabwe is a contracted form of 'dzimba-hwe,' which means ‘venerated houses’ in the Zezuru dialect of Shona - usually the houses or graves of chiefs. It is recognised as a World Heritage Site by Unesco. Infamously during the white government of Rhodesia it pressured archeologists to deny its construction by black Africans

[Simonchihanga/CC]

ANCIENT SPLENDOUR: The Great Zimbabwe dates back to the Gokomere people, an eastern Bantu subgroup, which lived in the area from around 200AD and flourished from 500AD to about 800AD. The stone city spans an area of 7.22 square kilometres (2.79 sq mi) and could have housed up to 18,000 people at its peak. It is suggested that Zimbabwe is a contracted form of 'dzimba-hwe,' which means ‘venerated houses’ in the Zezuru dialect of Shona - usually the houses or graves of chiefs. It is recognised as a World Heritage Site by Unesco. Infamously during the white government of Rhodesia it pressured archeologists to deny its construction by black Africans

[Simonchihanga/CC]

An African History of Africa: From the Dawn of Humanity to Independence

Zeinab Badawi, WH Allen, £25

ZEINAB BADAWI, reflecting today’s widely recognised view, begins this amazing story: “Everyone is originally from Africa and this book is therefore for everyone.”

She spent eight years touring Africa, researching this mammoth project. Her purpose was to write an “accessible and relatively comprehensive history of Africa” which, unlike that of most people’s experience which began with the arrival of Europeans, “reflected the continent’s rich history told by Africans themselves.”

The scene is set by a detailed exploration of several phases of man’s development on the African continent to arrive at today’s Homo sapiens-sapiens. This encompasses the first large-scale movements of populations of which there have been so many since.

ROGER McKENZIE expounds on the motivation that drove him to write a book that anticipates a dawn of a new, fully liberated Africa – the land of his ancestors

MOLLY DHLAMINI welcomes a Pan-Africanist and Marxist manifesto that charts a path for Africa’s resurgence

ROGER McKENZIE explains how Ibrahim Traore has sparked the flames of hope across Africa, while the Western powers seek to extinguish all attempts to build true sovereignty in the long-exploited continent