TONY BURKE speaks to Gambian kora player SUNTOU SUSSO

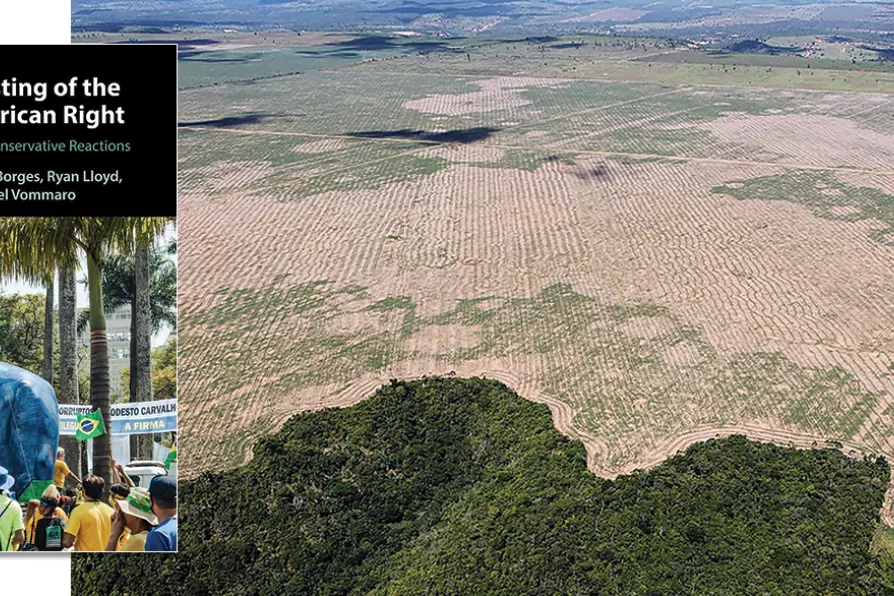

THE BOLSONARO EFFECT: Illegal logging at the Gurupi Biological Reserve and the Caru and Alto Turiacu indigenous lands in Maranhao province in northeastern Brazil

[Ibama/CC]

THE BOLSONARO EFFECT: Illegal logging at the Gurupi Biological Reserve and the Caru and Alto Turiacu indigenous lands in Maranhao province in northeastern Brazil

[Ibama/CC]

The Recasting of the Latin American Right: Polarisation and Conservative Reactions

Edited by Andre Borges, Ryan Lloyd, and Gabriel Vommaro, Cambridge University Press, £29.99

THE hidden backdrop to the rise of the far right in Europe has been the “silent revolution” of post-materialism identified in the late 1970s by Ronald Inglehart.

The embrace by a materially comfortable new generation of values reflecting non-material goals — from gender diversity to radical decolonial and racial theories — goes a long way towards explaining the positions staked out by the left in today’s culture wars.

The long-term secular trend suggests that those positions, however, are destined to fail, because not only has the mainstream left largely abandoned class as the organising principle of mobilisation, it is also losing the ephemeral cultural battles it has chosen to fight in its stead.

Latin America may still have a chance to avoid this historic error, even if all the signs suggest that the radical right in the region, witnessing their own left-wing adversaries repeat the mistakes of their European counterparts, has smelled blood.

Far-right forces are rising across Latin America and the Caribbean, armed with a common agenda of anti-communism, the culture war, and neoliberal economics, writes VIJAY PRASHAD

For the first time in years, the dominant voice within Chile’s official left comes not from neoliberal centrists but from the world of labour, writes LEONEL POBLETE CODUTTI