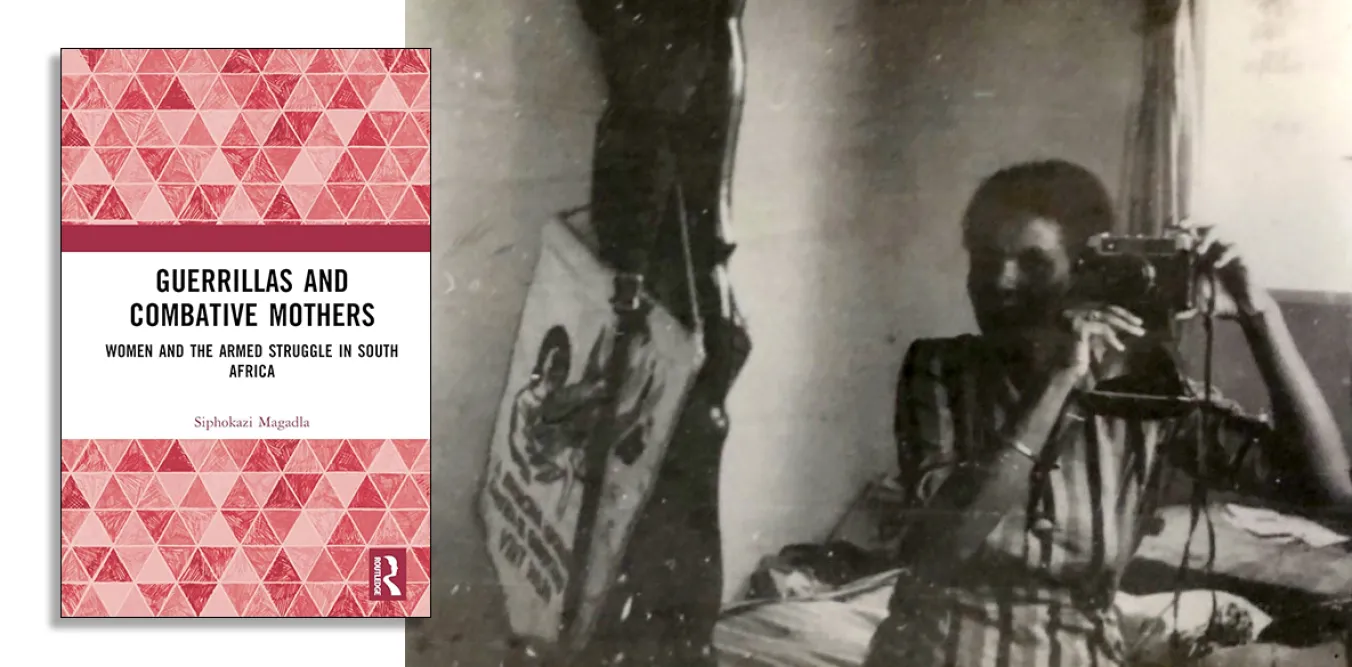

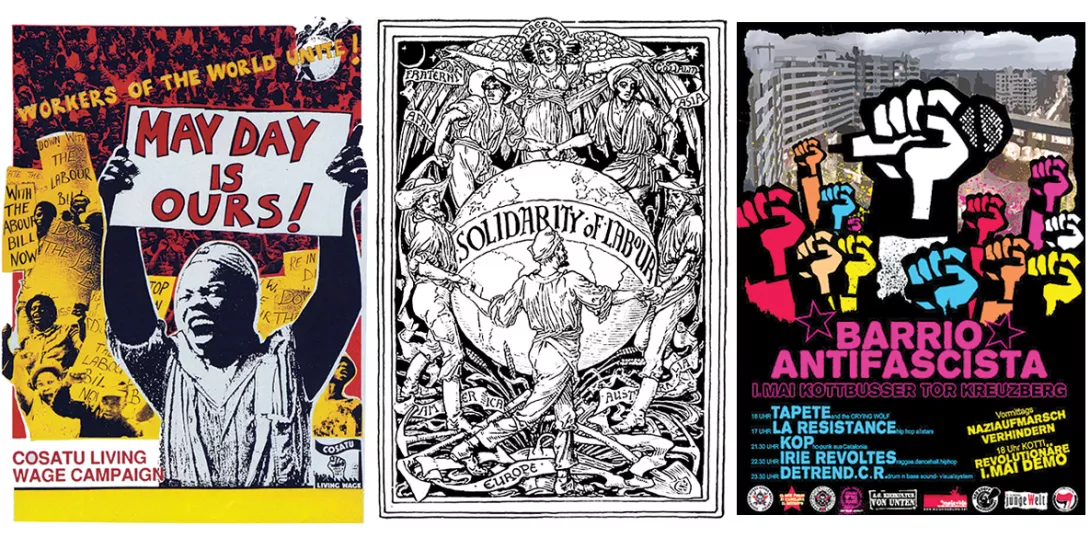

Dacha

by Anna Benn (words) and Fyodor Savintsev (photos)

Fuel £26.95

DACHAS are as much a state of mind as they are actual physical constructs.

They are a timeless cultural identity that evolved from an imperial legacy of recognition for services rendered — instead of an OBE you got a dacha — to what became an attainable, classless aspiration of city dwellers in the aftermath of the October Revolution.

Their association with the need for a retreat that offered physical and spiritual solace is, perhaps, best defined by Fyodor Dostoevsky in Crime and Punishment: “It was terribly hot outside, stuffy and crowded; everywhere there was whitewash, scaffolding, brick, dust and that certain summer stench so well known to every Petersburger who doesn’t have the means to rent a dacha.”

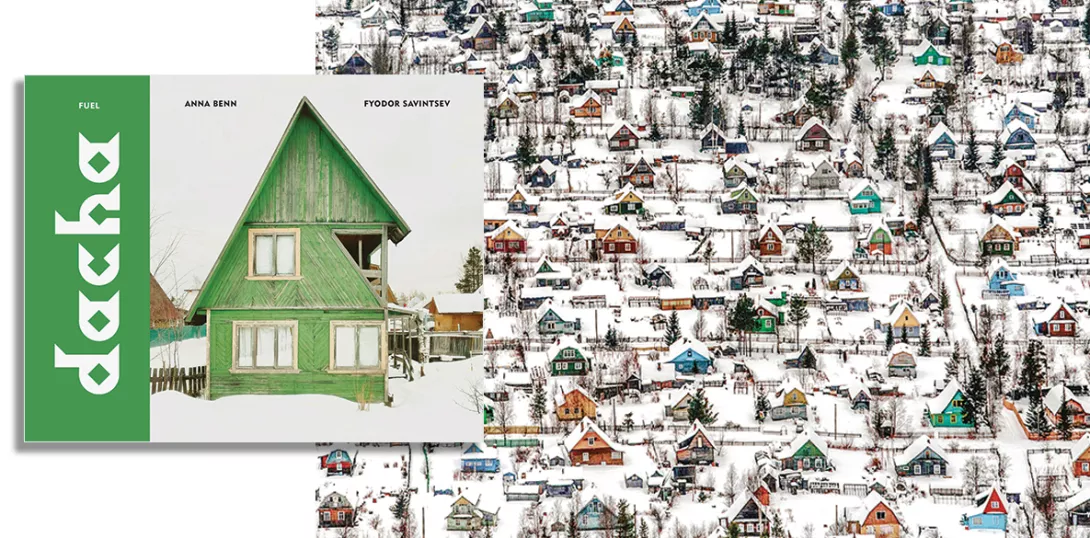

[[{"fid":"57592","view_mode":"inlinefull","fields":{"format":"inlinefull","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Udelnaya/Moscow region [Pic: Fyodor Savintsev]","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"inlinefull","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Udelnaya/Moscow region [Pic: Fyodor Savintsev]","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false}},"attributes":{"alt":"Udelnaya/Moscow region [Pic: Fyodor Savintsev]","class":"media-element file-inlinefull","data-delta":"1"}}]]

The etymology of the word itself is key: “dat” — to give, where the benefactor was the tsar and the usual beneficiary an individual from the upper echelons of society: servile intelligencia, the emerging nouveau riche, elements of the bourgeoisie, confidants and particularly valuable civil servants.

The landed gentry, however, would look upon it as a manifestation of vulgarity perhaps encapsulated best by Yermolay Lopakhin, a son of peasants turned developer, in Anton Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard.

“We will set up dachas, and our grandchildren and great- grandchildren will see a new life here,” Lopakhin announces, revealing his brave new world to the estate owner Lyubov Andreievna Ranevskaya in an attempt to persuade her to convert her cherry orchard to dacha plots.

“Dachas and dachniki, forgive me, but that’s so vulgar...,” comes the put-down riposte.

But, for better or worse dachas were there to stay. Poet Alexander Pushkin, intimate of St Petersburg elites, rented a 15-room dacha not far from where he would be killed in a duel. More significantly his landlord and dacha entrepreneur, Mr Miller, was once a butler to the tsar — a sign of the bourgeoisie getting their foot firmly in the door of Russia’s emerging capitalist economy.

Chekhov, Dostoyevsky, Pushkin and Osip Mandelstam would, however, turn in their graves in horror at the nouveau riche New Russians — who had made their fortunes from the collapse of the USSR — and their use of the pretentious neologism kottedzh (cottage) when alluding to their dachas.

Much like during the deadly cholera epidemic of 1848, which killed 12,000, the dachas provided an effective insulation from Covid contagion.

The dachas, beautifully photographed by Fyodor Savintsev, are rudimentary and unpretentious, utilitarian in design and mixing the styles of both peasant bothy and minor nobility dwelling. Clearly, however they also enjoy the affection and dedicated care of those for whom they provide solace, and the physical and spiritual regeneration that the proximity of nature offers as well an opportunity to forage for nature’s bountiful supplies — wild mushrooms in particular.

The land around the dachas also serves as an allotment and much produce will be ferried back into town to make preserves for the winter. Mushrooms would be dried and pickled much like gherkins, cabbage or beet, kompots will be made with cherries, apples, pears or gooseberries. Some of the fresh produce will make it to city street markets and supplement incomes.

For most “dachniki” these are their sacred space on Earth. “In the late 20th century, the dacha played a crucial part in the childhood of millions of Russians. Often presided over by grandparents, while parents worked in the city through the summer, Soviet children particularly recall the values instilled in them by their grandmothers the venerated matriarchs of the dacha,” writes Anna Benn.

Ironically, the dacha, a setting for countless Slavic fairy tales and rich folklore, is now on the brink of becoming a fairy tale itself.

The abolition of all regulation governing the dachas after the collapse of the Soviet Union placed it on an architectural endangered list. It has become a vanishing world in which a new breed of Chekhov’s Lopakhins have no time for sentimentality, cultural identity or indeed history. Their overriding concern is making a fast rouble — they know the proverbial price of everything but the value of nothing.

Savintsev, as evidenced by these images, is a passionate advocate of their conservation and restoration, and hence his mission to record these buildings for posterity and to arrest their imminent obliteration.

“If we do nothing to support it [the preservation], then nothing will be left in 20 years,” states architect Igor Shurgin who runs the Foundation for Maintenance of Wooden Architecture Monuments.

In the meantime, Vladimir Menshov’s Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTWA_7-ld_U, (1978), an anthem to dacha life which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1981, offers a tender remembrance of things past.

Dacha is sumptuous, engaging and deserving the highest accolade.

For more on the book, visit: https://fuel-design.com/publishing/dacha/