Coast of Teeth: Travels to English Seaside Town in an Age of Anxiety

by Tom Sykes and Louis Netter

Signal Books, £14.99

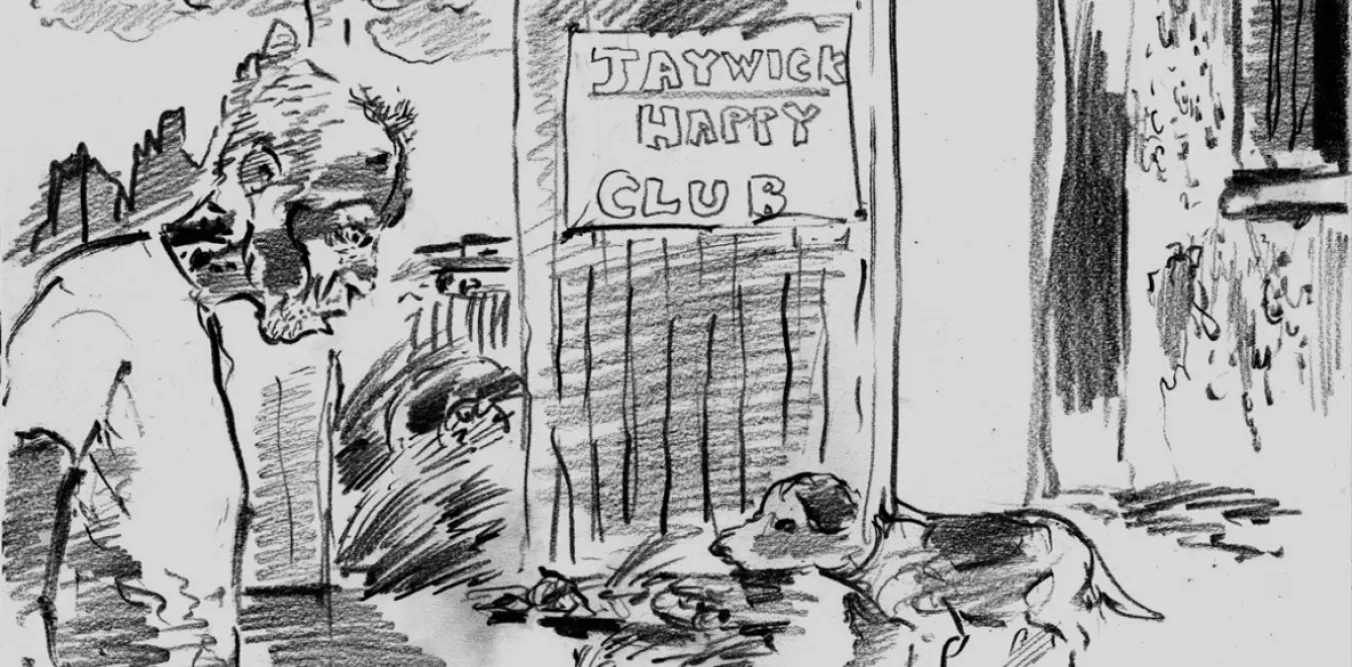

IF you have ever caught the train to Brighton of a weekend or bank holiday, you may have noticed the excited anticipation rippling through the carriage as it pulls into the station.

[[{"fid":"58156","view_mode":"inlineright","fields":{"format":"inlineright","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"inlineright","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":false,"field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false}},"attributes":{"class":"media-element file-inlineright","data-delta":"1"}}]]

All races, cultures, ages, sexes and even classes have the prospect of a day of earthly pleasure-seeking: wide and windy beaches stretch to the horizon, along with bad food, slot machines and shivering dips.