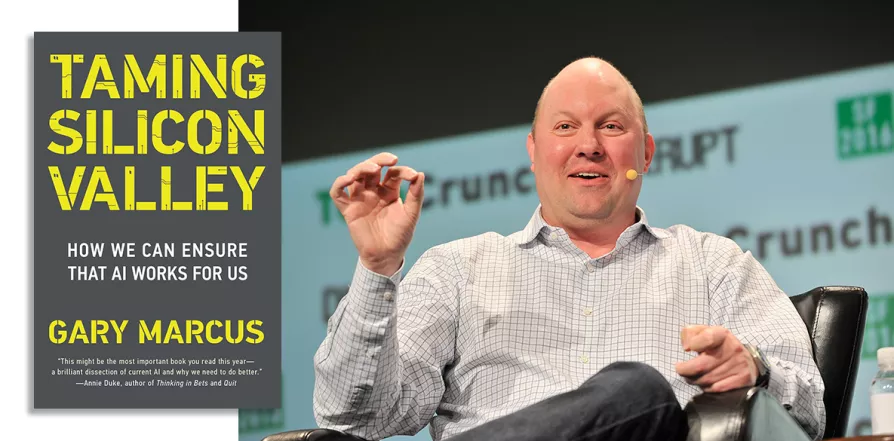

How Silicon Valley Unleashed Techno-feudalism

Cedric Durand, Verso, £18.99

THE term Techno-feudalism that appears in the title of Durands’ book is a new kid on the block in left-wing economic analysis. It represents the idea that capitalism “has been replaced by something worse,” to quote its best-known populariser, Yanis Varoufakis.

The New Left Review ran a debate on this in 2022, and critics such as Evgeny Morozov pointed out (see a recent piece in The Jacobin) that overestimating the radical nature of the current digital upheavals cited risks disarming long-standing critiques of capitalism. As earlier works like Lenin’s Imperialism show, capitalism has changed from its early small-factory basis into a tightly integrated and highly monopolised global economy, but this does not mean it is no longer capitalism.

However, while the last of the four sections in this book gives a neutral overview of that discussion, the book title is misleading in that it is not primarily concerned with what techno-feudalism may or may not be, but with analysing the last 50 years or so of the world economy and the role being played by digital technology. Here it is less speculative and more interesting.