ALISTAIR FINDLAY recommends the simple cadence, common prose, free verse, and descriptive power of a new collection by Julie McNeill

STEVE ANDREW enjoys a polemic against an unreformable and profoundly reactionary tradition

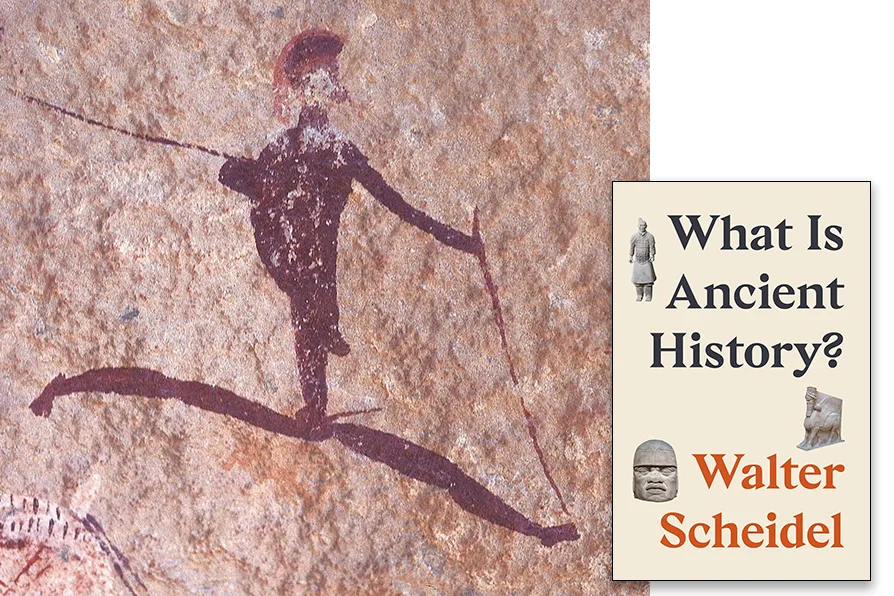

BACK TO THE BUSHMEN: Rock Art, cca 2000 BC by the San peoples, or Bushmen, members of the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of southern Africa, and the oldest surviving cultures of the region [Pic: Public Domain]

BACK TO THE BUSHMEN: Rock Art, cca 2000 BC by the San peoples, or Bushmen, members of the indigenous hunter-gatherer cultures of southern Africa, and the oldest surviving cultures of the region [Pic: Public Domain]

What is Ancient History?

Walter Scheidel, Princeton UP, £25

IT is not often that you read an academic text that is effectively an exercise in demolition directed towards another academic discipline, but this is exactly what this book is about, and a fascinating and thought-provoking read it proved it is too.

The victim in this case is the “classics” that claim to study ancient Rome and Greece, and the executioner is Scheidel, something all the more surprising given that his own academic work is actually rooted in this field!

And why? Largely because the author sees “classics“ as an intrinsically racist, Eurocentric and elitist discourse. The main reason to this being that the discipline values the study of ancient Rome and Greece above other equally salient civilisations that are typically either ignored altogether or only referenced in terms of how they impacted — or were influenced by — trade and commerce, and all of the attendant military conflicts that this gave rise to.

Turning his back completely on this unreformable and profoundly reactionary tradition, Scheidel convincingly argues instead for the creation of a more globally informed, cross-cultural and comparative approach that recognises all civilisations and is based upon shared foundational indices like animal and plant domestication, patriarchy, a division of labour with all the states, and the governments, money and taxes that are seen to have arisen from them.

In response to more anarchistic critics such as David Graeber, Scheidel makes the case that belief in overall trends does NOT always mean that all societies came to evolve on the same lines; or that, for example, societies might consciously combine hunter gathering and agriculture and revert from what were once seen as higher to lower modes of production.

Scheidel also criticises the classics on the basis of time and chronology, noting that if we were to talk about ancient history in the correct sense of the word it would be one focused on the Long Stone Age. And, in fact, Scheidel goes on to argue that a real deficit in knowledge and understanding that equally needs addressing is one around the global transition from hunter gatherer societies to ones more rooted in agrarianism.

As regards the accusation of elitism, Scheidel explores how selective the classics have been in their approach. They have, for example, very often disparaged history and instead prioritised language as a key to understanding. This was taken to ridiculous lengths in the widely influential and philologically dominated German university system, and likewise became very much embedded in the Anglo-American universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard and Yale, all of which continued to insist on qualifications in Latin and ancient Greek for all undergraduate courses well into the 20th century.

And, of course, what better way of keeping the working class out of their “universities” than this?

And finally, when Scheidel argues for an end to the classics, he brooks no compromise, with any so-called reform, in his mind, not only prolonging the agony of a dying discipline but potentially enabling it to recover.

In some ways this is a difficult — albeit intriguing — text and the thought did occur to me that the case might well be overstated. It’s not always obvious that classics have such a negative influence and Scheidel’s perspective is very much of the troubled insider looking outwards. Doesn’t his criticism of the classics also apply to other disciplines such as anthropology, which historically has its origins as a fundamentally racist and colonial discourse, but which rarely comes under the radar today?

Likewise, if this discipline was so irredeemable, then how might Marxist classicists such as the widely renowned G E M de Ste Croix and George Derwent Thomson have written such wonderful accounts about ancient Rome and Greece that continue to inform contemporary and popular works such as Michael Parenti’s The Assassination Of Julius Caesar?

Admittedly, there are no easy answers to any of this, but Scheidel’s passionate and detailed polemic about an area rarely given much attention certainly succeeds in putting many of these questions on the agenda.