Does widespread and uncontrolled use of AI change our relationship with scientific meaning? Or with each other? ask ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

In a stark warning of things to come JOHN ELLISON invokes the ideological splitting of hairs that weakened any and all opposition to the unravelling WWI when 22 million of mostly Europeans lost their lives and 23 million were maimed

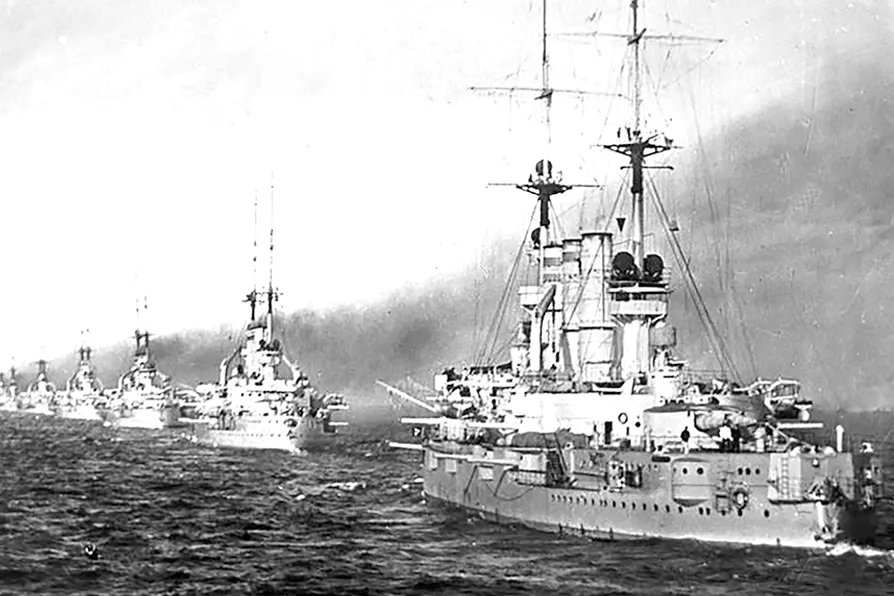

EXPLICIT INTENTION: A squadron led by five battleships of the Deutschland class in line astern formation in 1908 / Pic: German Federal Archives/CC

EXPLICIT INTENTION: A squadron led by five battleships of the Deutschland class in line astern formation in 1908 / Pic: German Federal Archives/CC

IF WE dive back into the past and into British newspapers during 1910, four years before the catastrophe of the first world war, anticipations of a future war with Germany can be found, especially in the small socialist sector, but not much expectation of a still wider war.

The radical liberal weekly The Nation was capable of serious insights. It declared, on the first day of 1910: “Those who have followed recent controversies, who have read the Temps or the books of such semi-official authors as M Tardieu and M Meville, cannot but fear lest an only nominally secret convention had bound us now for several years to render military and naval aid to France in the event of a German attack …”

In February, The Socialist, Glasgow-based monthly of the Socialist Labour Party, and with a readership of a few thousand, was forthright in analysis: “Germany, in attacking Britain, despoiling her of her colonies, and ruining her as a maritime nation, would only be following in Britain’s footsteps.

“Capitalism imposes upon the capitalism of all lands the necessity of finding an outlet for the mass of commodities which, as the system develops, the home market in each country becomes less and less able to absorb.

“Britain, through being first in the field, has pegged off large tracts of the Earth’s surface for her own private use and exploitation. Germany, having rapidly developed into a first-class military power, finds herself confronted on the seas by Britain’s immense navy.

“Until that navy is destroyed, German industries will not develop fast enough to suit German capitalists. A life and death struggle between English and German capitalists is inevitable.”

In January’s general election (1910), Labour candidates gained 40 seats (six being nominees of the Independent Labour Party), 38 more than a decade before. but were subject to the criticism that most (but not Keir Hardie) were really liberals.

In spring and summer 1910 increased Naval Estimates [annual financial and operational plans for a nation’s navy] were accompanied by alarmism in the “Jingo press.”

An additional 10 millions were allocated to the cost of naval ship construction. The justification was “the growth of the German fleet”.

But Hardie pointed out on July 22 that Germany’s ocean-going commercial fleet was about a fifth of the size of Britain’s: “So there is nothing there to be alarmed about,” he added.

But there was. Both the German and British governments were enlarging the danger of future war.

Caroline Benn’s biography of Keir Hardie comments that he (and others) had “the mistaken conviction that the ordinary workers who never came to conferences or belonged to parties were as internationalist as those who did.”

The Social Democratic Party led by Henry Hyndman had influence though divided between left and right, with Hyndman on the right, with imperialism in his DNA, and no SDP MPs [The Social Democratic Party “emphasised personal liberty, social welfare, and social equality, moving away from revolutionary Marxism”].

The party’s paper, Justice, carried on August 20 1910 a remarkable letter challenging him.

Here are some relevant extracts: “Of course, Germany desires to be a great world-wide imperialist power — the governing class of every nation desires it, for it means additional trade, advantages and profit for itself; but since when has it been a principle of social democracy that the only nation, or rather, the only capitalist class, to be allowed this is the English? Why this sudden greater faith in English than in German capitalism?

“Surely India, Ireland, Egypt, the help given to Russia in suppressing Persia, and so forth, are sufficient to show that it is at least but six of one to half a dozen of the other. Certainly English political conditions are superior to those obtaining in Germany, but we know perfectly well that this is not due to any inherent qualities in the English governing class, but rather to her previous economic development …

“… it is surely ridiculous for England to pose as the defender of the sacredness of treaties … as witness what happened, say, in Egypt and Cyprus. As for defending the smaller nationalities, the idea is distinctly rich.

“If the SDP does not speedily, and in no uncertain voice, repudiate such bourgeois imperialist views then goodbye to it as a serious force in the national and international socialist movement …”

The letter’s author was Zelda Kahan, then a young woman of Lithuanian origin, who had come to Britain as a child. (Much later she would co-author, with her husband William Coates, a history of Anglo-Soviet Relations published in 1943.)

Her use of the word “English” to mean “British” was common at the time, and shared by others quoted here.

That the weakness of the anti-war socialist movement was as pronounced on the continent as it was at home is demonstrated by the recollections of the Socialist Congress in Copenhagen in late August of then Russian exile (and future Soviet ambassador to Britain) Ivan Maisky, in his Journey into the Past.

Though well-attended by delegates from European countries, the “fast-approaching danger of war … took second place” to a lengthy discussion about trade union unity in Austria.

This was, Maisky considered, against the background that too many delegates believed that the needs of international trading relationships, and the psychology of civilised humanity, ruled out such a war.

Secret information came to poet, diarist, anti-imperialist and wealthy land-and race-horse-owner Wilfrid Scawen Blunt as to the practicalities of British support for France if war occurred from his cousin, George Wyndham, and into Blunt’s diary (published post-war) on October 13 1911: “He says that it is absolutely known to him through his former connection with the War Office that it was part of the Entente with France that, in case of war with Germany, an English contingent of 160,000 men should be placed on the continent in support of the French army … the extreme north-west of the French line from Calais would be the scene of the English operations.”

Blunt’s diary on January 4 1912 tells of a visit to him by Theodore Rothstein (a Russian Marxist SDP member and London correspondent of Continental newspapers), and summarises Rothstein’s position about European affairs. “He says true reason the German government would not fight this year was not any doubt of the superiority of its army, which is infinitely more powerful than the French, but because it had not the mass of the people with it.

“He says, however, that Germany is of one mind to fight England on the first occasion, as they were very angry with us, far more so than with the French. All now are for war, except the socialists, and even these are not all of them against it.”

On April 30 1913, Rosa Luxemburg (of Polish origin), a formidable German socialist leader, set the scene for the war to come in words as powerful as imaginable: “Armaments and wars, international contradictions and colonial politics accompany the history of capitalism from its cradle.

“In a dialectical interaction, both cause and effect of the immense accumulation of capital and the sharpening of the contradictions that go with it — internally between capital and labour; externally between the capitalist states — imperialism has opened up the final phase, the division of the world by the assault of capital.

“A chain of unending, exorbitant armaments on land and on sea in all capitalist countries because of rivalries; a chain of bloody wars which have spread from Africa to Europe and which at any moment could light the spark which would become a world war.” Imprisoned during much of the war, Luxemburg was to be assassinated on January 15 1919 by the right-wing paramilitary Freikorps/Volunteer Corps commanded by Waldemar Pabst.

The die was cast. Blunt wrote on August 5 1914, the day after Britain’s declaration of war: “And now at last we are to fight for what? For Servia, a nest of murderous swine which has never listened to a word of English remonstrance. For Russia, the tyrant of Poland, Finland and all northern Asia, for France, our fellow brigand in North Africa and lastly for Belgium with its Congo record. And we call this England’s honour!” Said in shock, but all criticism was swiftly drowned out by calls to fight.

In today’s scenario calls to fight must be drowned out by calls of “No to imperialist war.”