JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

ELIZABETH SHORT recommends a bracing study of energy intensive AI and the race of such technology towards war profits

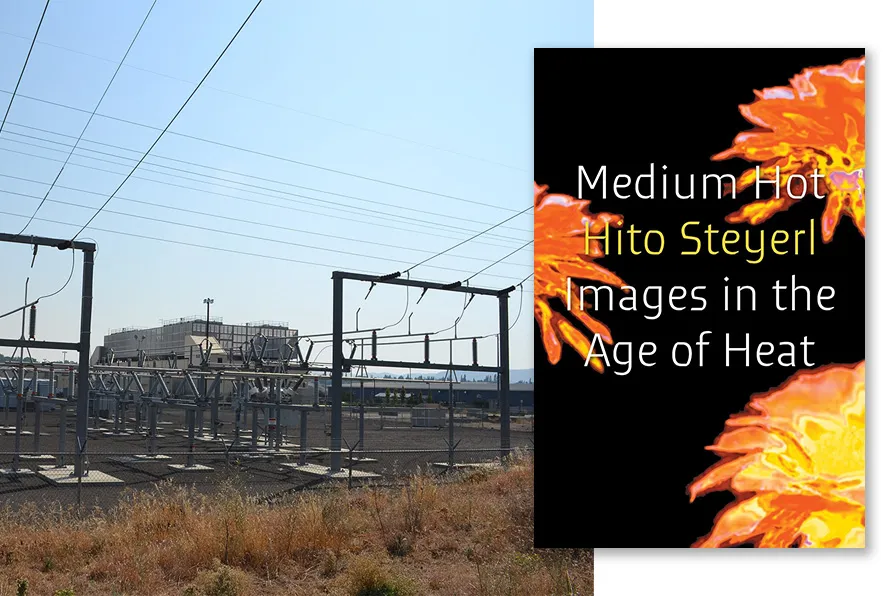

MONSTROUSLY ENERGY INTENSIVE: Google has 62 data centres throughout the world. One of the largest, pictured, is located in the town of The Dalles, Oregon, on the Columbia River, approximately 80 miles from Portland. / Pic: Visitor7/CC

MONSTROUSLY ENERGY INTENSIVE: Google has 62 data centres throughout the world. One of the largest, pictured, is located in the town of The Dalles, Oregon, on the Columbia River, approximately 80 miles from Portland. / Pic: Visitor7/CC

Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat

Hito Steyerl, Verso, £17.99

IS AI fuelling cultural stagnation, and how quickly are we sacrificing the planet in the process? These are the kind of questions that surface while reading Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat, the latest collection of essays by artist and theorist Hito Steyerl.

The book turns its attention to the accelerating forces shaping our visual culture in the age of AI, and does so with Steyerl’s signature blend of critical theory, dry wit and sharp eye for the surreal contradictions inherent in our digital era.

One chapter opens with a statistic so absurd it almost resists comprehension: in 2023, 500 minutes of video were uploaded every second — 30,000 times the amount of time that had passed. The scale alone is disorienting, but Steyerl’s concern lies deeper.

We are, she argues, already living within an aesthetic feedback loop, where vast data collections “incentivise popular and uncontroversial statistical recombinations of earlier popular and uncontroversial styles”. Digital cultures don’t evolve so much as they recycle and “converge towards this mean, orbiting around median styles, notions and images, creating a narrow mainstream.”

An example of this is the prevalence of the Edison-bulbed, industrial “International Airbnb Style” which has also become dominant in coffee shops across the world, a phenomenon highlighted in Alex Murrell’s essay The Age of Average. AI image generation optimises this churning out of the mundane, fostering a cultural standstill Steyerl rightly deems “surprising” in an era of widespread crisis.

It may be naive optimism, but I wonder if AI’s tendency to gravitate toward the average may be the very flaw that keeps human creativity not just relevant, but essential — for now.

Still, being visually dull is one thing; becoming a genuine threat to humanity is quite another. The book delves into how the whole process of fuelling this cultural stagnation is monstrously energy-intensive. Steyerl quotes that by 2034, energy used solely by data centres is expected to match the energy consumption of the whole of India. The sheer amount of energy required predisposes the planet towards an inevitable double-downing on fossil fuels.

To put this into perspective, US think tank Energy Innovation estimates that hyperscale data centres can demand as much as 100 MW, enough to power 80,000 homes. Labour’s plan to power Britain with “clean energy” by 2030 will be made even more unlikely thanks to proposed AI Growth Zones, which relax planning restrictions for data centre developments.

With Keir Starmer vowing to “win the global race” for AI, it will be interesting to see how Britain will align this with its climate commitments — all logic points to the reality that it won’t.

The rhetoric of the obsession with the “AI race” is something Hito centres on. The racing visuals in The Hardest Part https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Nb-M1GAOX8, one of the first music videos created by Sora, a video generator developed by OpenAI, is explored as a metaphor for this frantic pursuit.

But broadly, she reflects how the very notion of the unavoidable race paves the way for a national security-based war economy. After all, war zones provide the perfect testing ground for AI, and the defence industry remains one of the most lucrative markets for the technology.

Another chapter reflects on AI’s inconsistencies with portraying humans, who sometimes end up missing limbs. Their absence, Steyerl notes, may “indicate that any mitigation efforts to prevent future health and social hazards created by profit maximalisation within AI industries are woefully inadequate, if not missing altogether.”

She also looks into the absurd economy of underprivileged and underpaid “ghost workers” who sift through vast data-sets, tagging and identifying material to censor. She cites one research project which uncovered how Syrian digital workers in Germany had to filter and review images of their own hometowns, destroyed by an earthquake in the region.

“They were deemed too violent for social media consumers, but not for the region’s inhabitants, who had been expelled by war and destruction and were forced to become ghost workers in exile,” Steyerl writes.

She also predicts that it is likely that workers such as web designers and PR professionals will increasingly have to rent AI services built using their own stolen labour in order to become competitive in their respective fields. People already roped into Adobe subscriptions will likely find this scenario all too familiar. It also underlines the need for strict regulation and proper fixed term contracts.

With the gig economy growing, and pay struggling to keep up with inflation, the last thing workers need are more mandatory subscriptions to tech overlords that eat into already volatile earnings.

While you may think that one could get weighed down by reading all about the grinding out of fossil-fuel powered visual slop, and evil war-capitalising profiteers, there are glimpses throughout the book of what alteratives could look like.

One avenue could be for privatised data to be redefined as cooperatives — a kind of data commons, although it’s noted that there is the question of how royalties would be distributed. Another tried-and-tested method that’s mentioned would be proper taxation on firms to feed money back into the public.

We could also see the rise of small-tech firms, as an alternative to big tech oligarchy conglomerates. Such firms could operate using “minimum viable configurations” — consuming less energy — and be powered by renewables.

But perhaps one of the most galvanising reminders Steyerl cites comes from economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, whose work shows that social progress is distinct from technological progress. Their research noted that the productivity benefits of technology have never been voluntarily shared by their profiteering owners.

“To put it briefly, social progress was created by social movements, not by inventors or tech companies.”

JOHN GREEN wades through a pessimistic prophesy that does not consider the need for radical change in political and social structures

ANDY HEDGECOCK admires a critique of the penetration of our lives by digital media, but is disappointed that the underlying cause is avoided

GUILLERMO THOMAS recommends a useful book aimed at informing activists with local examples of solidarity in action around the world

ALAN SIMPSON warns of a dystopian crossroads where Trump’s wrecking ball meets AI-driven alienation, and argues only a Green New Deal can repair our fractured society before techno-feudalism consumes us all