The Bard stands with the Reformers of Peterloo, and their shared genius in teaching history with music and song

Generous helpings of Hawaiian pidgin, rather good jokes, and dodging the impostors

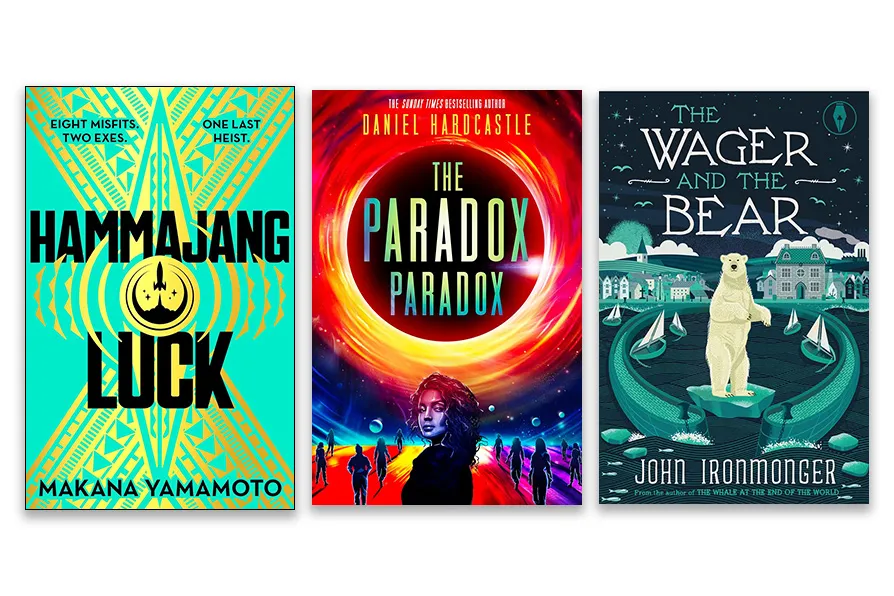

IN a working-class Hawaiian community living in a space station, Edie has just been released from eight years on a miserable prison planet in Hammajang Luck by Makana Yamamoto (Gollancz, £20).

This time she has to go straight: her family needs her. But blacklisted, broke and in debt, it’s not long before she surrenders to the siren voice of Angel, her former best friend. Angel has a foolproof plan for the greatest long con the galaxy’s ever seen — relieving a tech trillionaire of a large part of his entirely ill-gotten fortune.

There are two big problems. One is that Edie has been in love with Angel since they were at school together, so can she trust her own judgement? And the other is that this is the same woman whose betrayal landed her with her jail sentence during their last job together. Is she really going to trust Angel again?

This sparky debut delivers all the tension that heist fans demand, and as a bonus you’ll learn enough Hawaiian Pidgin to order a meal or have an affair.

I won’t attempt to summarise the plot of The Paradox Paradox (Unbound, £20), Daniel Hardcastle’s sprawling time travel tragicomedy, except to say that the universe (in fact, several universes) need saving from a monomaniacal genius, and that the only people who can achieve that is a hand-picked gang of sad losers.

It’s a book recommended to anyone who is an enthusiast for stories involving alternative timelines, temporal dilemmas in which travellers cross their own paths, ridiculous scientific theories that become more convincing the dafter they get, lots of rather good jokes, and of course paradoxes about paradoxes.

In a pub in a coastal town in Cornwall, in The Wager And The Bear by John Ironmonger (Fly on the Wall Press, £11.99), a boy named Tom, who’s been studying earth sciences at university, is back home for the summer and catching up on what he’s missed in the way of local gossip and local cider.

When the constituency’s MP, a pompous climate-denier, enters the pub, tipsy Tom can’t resist goading him into an argument. Someone’s phone films the politician’s humiliation, and the resulting video comes to frame the rest of both men’s lives, spent in a world of rising seas and vanishing clouds.

Yes, this is another climate change novel; yet another one, as those who are beginning to fear they’ll spend every day between now and the end of the world reading climate change novels might groan. But this one is fun. Ironmonger’s settings are explorable, and his characters the more intriguing the more you get to know them. His writing is warm and witty; this may well be a book you’ll read more than once.

It’ll sing different songs to different readers. What I heard was the importance of avoiding capture by pessimism or optimism, those vampiric impostors, and instead finding a praxis that is based on realism, hope and above all on doing.

Timeloop murder, trad family MomBomb, Sicilian crime pages and Craven praise

A novel by Argentinian Jorge Consiglio, a personal dictionary by Uruguayan Ida Vitale, and poetry by Mexican Homero Aridjis