MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review "Wuthering Heights", Little Amelie or the Character of Rain, Crime 101, and Stitch Head

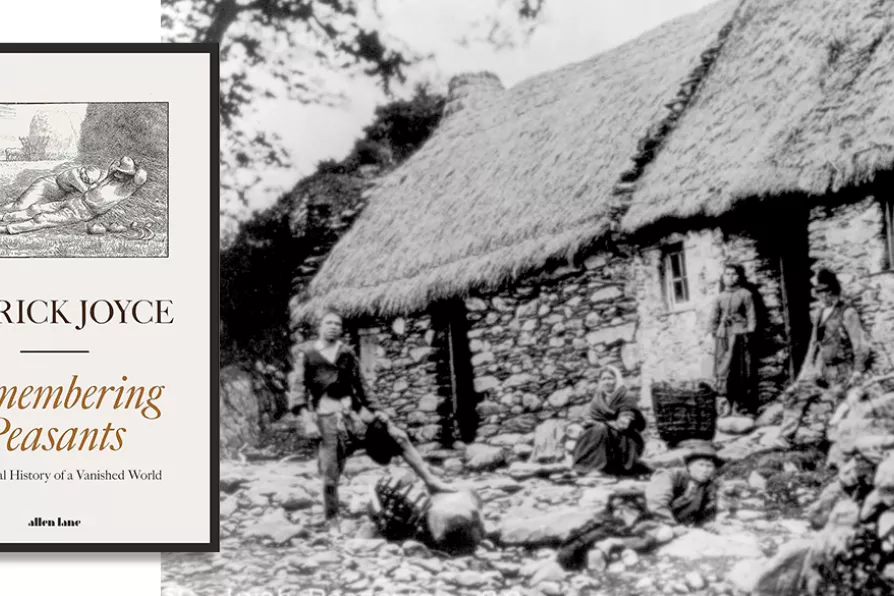

Irish peasants, 1880

[Library of Congress/CC]

Irish peasants, 1880

[Library of Congress/CC]

Remembering Peasants: A Personal History of a Vanished World

Patrick Joyce, Allen Lane, £25

RARE for a book to change your self-perception; to give you not exactly a new perspective on your place in the great scheme of things, but a much richer sense of yourself there. Reading this book you realise what you have always known, though only now can recognise: you are a descendant of peasants and you carry that inheritance even as you live your urbanised, corporatised, “iron cage” life, as Max Weber described it.

In historian Patrick Joyce’s labour of love, Remembering Peasants, a wealth of cultural testimony draws the reader deep into an understanding of the difference in world view of the peasant. From “Joyce country” in the West of Ireland, through France, Italy, Poland and further east, the underlying nodes of existence from the soil are shown in the development of systems of mentality.

Survival is the key imperative. Joyce shows how the peasant represents a history of want and exploitation, but above all the tenacity for survival. Although he warns how “there should be no idealisation of a class that has to define itself as the class of those who survive.”

FIONA O'CONNOR recommends a biography that is a beautiful achievement and could stand as a manifesto for the power of subtlety in art

FIONA O’CONNOR is fascinated by a novel written from the perspective of a neurodivergent psychology student who falls in love