JAN WOOLF ponders the works and contested reputation of the West German sculptor and provocateur, who believed that everybody is potentially an artist

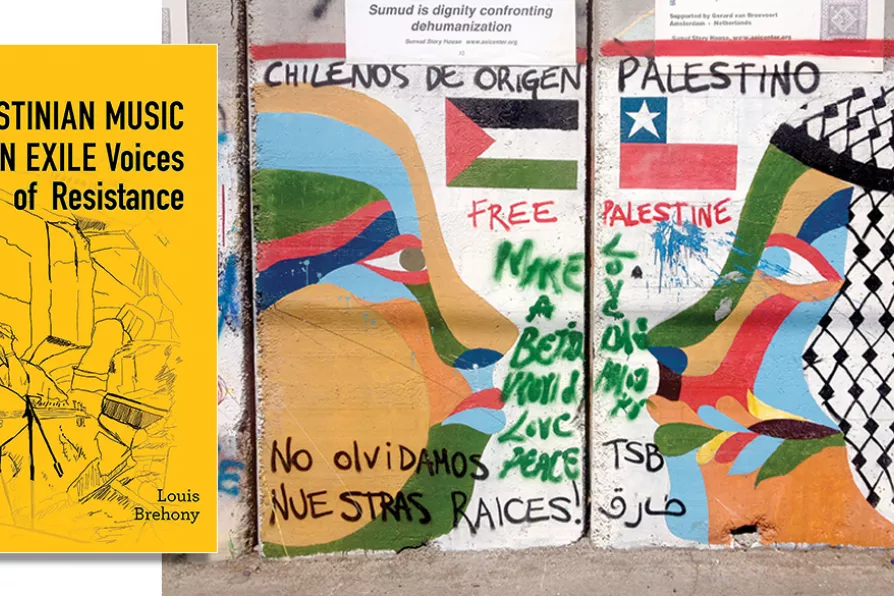

MEMORIES NEVER LOST: Mural narratives on the Wall Museum of the Sumud Story House in Bethlehem: ‘Chileans of Palestine ancestry - we never forget our roots,' 2018

[Jj M Htp/CC]

MEMORIES NEVER LOST: Mural narratives on the Wall Museum of the Sumud Story House in Bethlehem: ‘Chileans of Palestine ancestry - we never forget our roots,' 2018

[Jj M Htp/CC]

Palestinian Music in Exile: Voices of Resistance

Louis Brehony, American University in Cairo, £49.95

MUSICIAN, activist and prominent scholar of Palestinian music, Louis Brehony performs a deep dive into the origins and significance of 20th century post-Nakba melodies while exploring how longstanding traditions, as well as decades of occupation and exile, have shaped the development of various genres of Palestinian music.

Brehony further explores how music has served as a medium for preserving Palestinian culture under the yoke of Israeli oppression, while also serving as a powerful form of non-violent resistance to occupation and keeping alive the hope that Palestine will one day shake off the chains in which it has been bound for decades.

Brehony interviews numerous musicians of Palestinian origin, such as Reem Kelani and Ahmad al-Khatib, who have found varying degrees of fame, to learn how their childhood experiences or diasporan existence in adulthood drew them to music and led them to create their own performance styles.

MARJORIE MAYO recommends a disturbing book that seeks to recover traces of the past that have been erased by Israeli colonialism

GEORGE FOGARTY is stunned by the epic and life-affirming sound of an outstanding Palestinian musical collective