MARIA DUARTE picks the best and worst of a crowded year of films

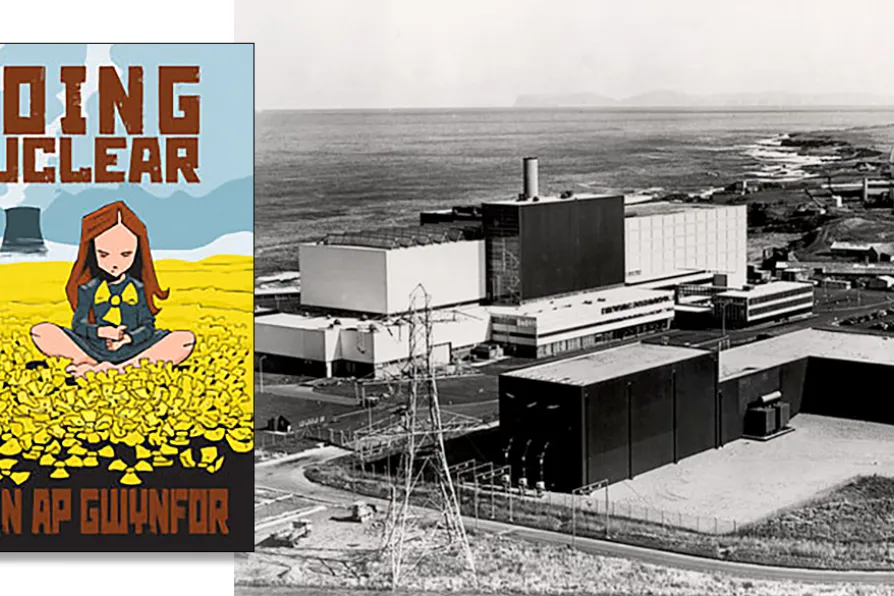

DEADLY: The 250-MWe Dounreay prototype fast reactor in Scottland (large white and black building) which began generating electricity since 1975 alongside the Vulcan Naval Reactor Test Establishment (NRTE), a military submarine reactor testing facility

[Public Domain]

DEADLY: The 250-MWe Dounreay prototype fast reactor in Scottland (large white and black building) which began generating electricity since 1975 alongside the Vulcan Naval Reactor Test Establishment (NRTE), a military submarine reactor testing facility

[Public Domain]

Going Nuclear

Mabon ap Gwynfor, self-published, £13

Going Nuclear by Plaid Cymru’s Senedd Member Mabon ap is a detailed examination of the links between the civil nuclear industry and how it subsidises and sustains Britain’s military nuclear capability.

The author lives in north Wales and is also the newly elected chair of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament Cymru.

Curently, in the the world’s difficult journey to net zero, protagonists for nuclear energy argue that we need it in the energy mix for those days when the sun is not shining and the wind refuses to blow.

MARK JONES responds to issues raised in the recent report from Richard Hebbert on the Communist Party’s Congress debate on nuclear power

The Communist Party of Britain’s Congress last month debated a resolution on ending opposition to all nuclear power in light of technological advances and the climate crisis. RICHARD HEBBERT explains why

For 80 years, survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings have pleaded “never again,” for anyone. But are we listening, asks Linda Pentz Gunter