GORDON PARSONS applauds a marvellous story of human ingenuity and youthful determination, well served by a large and talented company

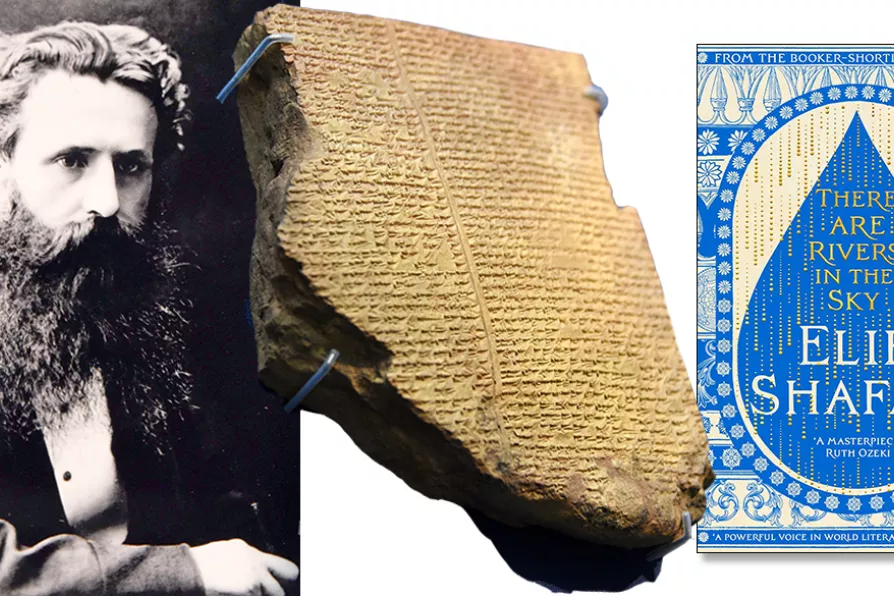

(L) George Smith, an assistant at the British Museum in London, who transliterated and read the cuneiform inscriptions on Tablet XI of the Epic of Gilgamesh in 1872. The inscriptions narrate a story that is very similar to the Biblical story of Noah's Ark and the Flood in the Book of Genesis. (R) Tablet XI which dates back to the Neo-Assyrian Period, 7th century BC.

[Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin/CC]

(L) George Smith, an assistant at the British Museum in London, who transliterated and read the cuneiform inscriptions on Tablet XI of the Epic of Gilgamesh in 1872. The inscriptions narrate a story that is very similar to the Biblical story of Noah's Ark and the Flood in the Book of Genesis. (R) Tablet XI which dates back to the Neo-Assyrian Period, 7th century BC.

[Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin/CC]

There Are Rivers in the Sky

Elif Shafak, Viking, £18.99

RAINDROPS as metaphor for historical memory is a clever narrative device that Shafak exploits to the full, taking us from ancient Mesopotamia, via the British Museum in Victorian Britain to modern-day Turkey, where a young Yazidi girl is reminded by her grandmother of the ancient history of their country in which the Yazidis are still a persecuted minority.

Melding fiction with real historical events and figures, Shafak creates a fascinating story that intertwines individual lives with historical events, involving class, race and colonialism.

The novel begins in ancient Mesopotamia, when a raindrop falls on the head of despotic ruler Ashurbanipal. He owns an extraordinary library of clay tablets which includes the Epic poem of Gilgamesh. We fast forward to mid-Victorian London, where the raindrop becomes a snowflake, settling on Arthur Smyth — also based on a real historical figure — as he is born in midwinter to a destitute mother on the banks of the Thames. The Victorian Assyriologist George Smith was indeed a self-taught working-class boy who became an expert in the interpretation of ancient cuneiform writing, but Shafak’s retelling of his life turns it into a fairy-tale, undermining its validity as a perceptive commentary on class.

GORDON PARSONS is enthralled by an erudite and entertaining account of where the language we speak came from

PETER MASON is enthralled by an assembly of objects, ancient and modern, that have lain in the mud of London’s river