JAN WOOLF finds out where she came from and where she’s going amid Pete Townsend’s tribute to 1970s youth culture

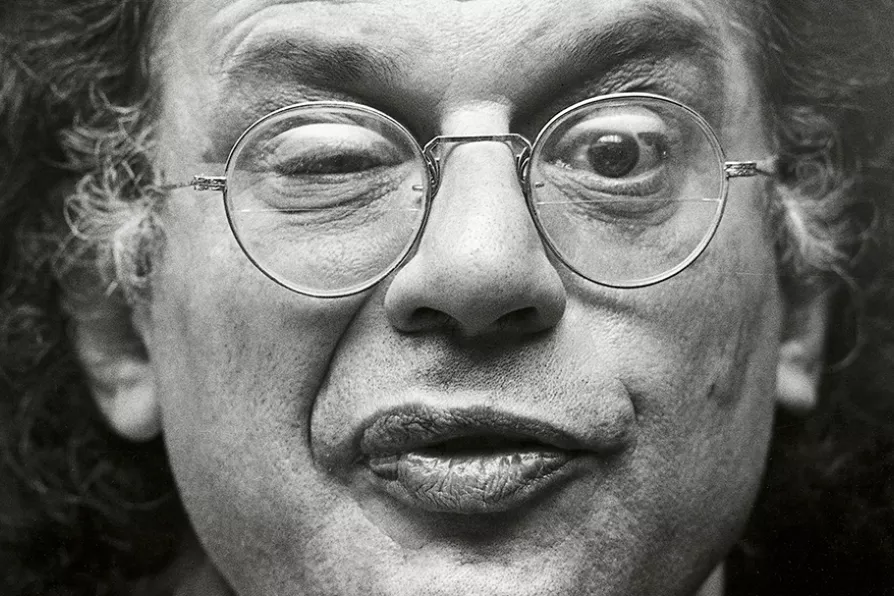

Alan Ginsberg, 1979

Alan Ginsberg, 1979

THE publication last year of Steven M Weine’s Best Minds: How Allen Ginsberg Made Revolutionary Poetry from Madness has reinvigorated enduring questions about the relationship between mental health and creativity.

Weine frames “madness” as culturally ascribed, but “mental illness” as clinical. The latter is pathologised according to what Michel Foucault called the “clinical gaze” of society’s institutions. Its definitions are subject to ideological and technocratic shifts in those societies.

An example is the United States at the height of cold war paranoia and Jim Crow, and the civil rights, black nationalist and anti-war movements which were a direct rebuttal to a dehumanising politics. This was a society that pathologised “otherness.” A picture-perfect patriotic citizenry of White, middle-class, heterosexual, family oriented consumers was the norm. Deviations were viewed with suspicion. They represented a threat to be neutralised or, failing that, contained for the sake of the nation’s “integrity” and security.

Allen Ginsberg called this a “Syndrome of Shutdown”: a “healthy” society was one that, in offering material abundance (to a select citizenry), asked for unquestioning conformity, the denial of body and individual consciousness, experience, language.

US poets such as Ginsberg and Bob Kaufman, both of whom experienced mental health issues and confronted those experiences in their art, ruptured these structures. They illuminated the individual human toll of struggling against such a climate of fear and numbness.

In doing so, they exposed the sickness of the society that sought to pathologise and contain them.

As a psychiatrist, Weine brings a distinct perspective to Ginsberg. He hits all the major ports, especially those pertaining to the relationship between poetry and Ginsberg’s mutable understanding of “madness.”

From a young age, Ginsberg witnessed the harrowing struggles of his mother Naomi with paranoid schizophrenia. She spent two decades in and out of psychiatric hospitals.

Ginsberg’s own experience at the Psychiatric Institute of the Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, where he was a patient for eight months in 1949, was catalytic. It is where he met Carl Solomon, the dedicatee of Howl, his best-known poem. It also sowed the seeds of a poetics of compassion and healing, which Ginsberg would develop throughout his career.

Howl is a candid, incantatory Jeremiad of witness and lament, and a cry of human compassion and salvation. The opening line, though one of the most overquoted in 20th-century American poetry, is not as clear a declaration as it seems:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving, hysterical, naked

Is this “madness” innate in the “best minds,” or is it thrust upon them from without? Is it the destructive madness of society itself?

There is a deliberate ambiguity here, which Ginsberg in part clarifies with the question-and-answer at the beginning of the poem’s second section:

What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imaginations?

Moloch!

The modern metropolis takes on the form of Moloch, the child-devouring pagan god of the Old Testament. It is monstrous, sustained by the sacrifice of innocents.

Moloch whose love is endless oil and stone! Moloch whose soul is electricity and banks! Moloch whose poverty is the specter of genius! Moloch whose fate is a cloud of sexless hydrogen! Moloch whose name is the Mind!

This Mind, synonymous with Moloch, is one conditioned to alienate any human value. It is an abstracted intellect, so severed from the heart and body that it bore the hydrogen bomb. To be out of this Mind, then, may be to retain your humanity. But this makes you a problem for society.

As Weine points out, Ginsberg understood this in terms of the bivalent nature of madness as “either liberatory or damaging.” His exploration of the tension between these perspectives led him to “blow these concepts wide open in his poetry.”

This coincided with the opening up of Ginsberg’s verse to a long Whitmanic speech-based breath: to expansive lines, incantatory repetitions, declarations, reportage, catalogues of images.

It is no coincidence that, in addition to Walt Whitman, Howl was inspired in part by Christopher Smart’s poem Jubilate Agno, which Smart wrote while confined to an asylum for what is now believed to have been manic depression. Ginsberg also drew on Ode to Walt Whitman by Federico Garcia Lorca, who also suffered from depression and anxiety over the discovery of his homosexuality, and the first prelude of At the Top of My Voice by Vladimir Mayakovsky, who committed suicide in 1930.

When Ginsberg insists, in the third part of Howl, that “the soul is innocent and immortal it should never die ungodly in an armed madhouse,” he points to a life beyond the structures that pathologise and contain that which is, in essence, divine and uncontainable.

Ginsberg would refine his poetics in subsequent works, such as Kaddish (1962), a wrenching threnody and loving eulogy for his mother, who died in Pilgrim State Hospital not long before the publication of Howl.

Ginsberg’s countercultural credentials were ratified by the obscenity trial over Howl in San Francisco during the summer of 1957, which brought the “Beat Generation” to national attention.

But the Beat poet par excellence is Bob Kaufman.

[[{"fid":"67107","view_mode":"inlineleft","fields":{"format":"inlineleft","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Bob Kaufman (1925 - 1986) - Credit: Public domain","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false},"link_text":null,"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"inlineleft","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Bob Kaufman (1925 - 1986) - Credit: Public domain","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":false}},"attributes":{"alt":"Bob Kaufman (1925 - 1986) - Credit: Public domain","class":"media-element file-inlineleft","data-delta":"1"}}]]Kaufman was a dextrous and mellifluous jazz poet. He is regarded as a great American surrealist. The popularity of his poetry in France led to him being dubbed, somewhat fetishistically, “the black American Rimbaud.” The iconic poete maudit, Rimbaud famously declared: “The poet makes himself a visionary through a long, boundless, systematised disorganisation of the senses.”

Kaufman fused these influences into an improvisatory, impressionistic, candid poetics. His verse was largely composed on the tongue and recited in the moment, often in public spaces such as cafes and streets. Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, recalled first seeing Kaufman when the poet stuck his face, covered in bandages, through the open windows of tourists’ cars and started “babbling” his poetry.

Such public disruptions by a black man in the segregationist US did not go unnoticed by city authorities. Kaufman was constantly harassed, jailed and even beaten by police. This happened so often that the Co-Existence Bagel Shop, a bohemian hangout where Kaufman was a fixture, kept a collection tin on the counter for his legal costs.

Kaufman endured periods of drug addiction, erratic behaviour and destitution. His struggles with mental health were in no small part due to the trauma and brutality of his experiences. Following his arrest on the trumped-up charge of walking on the grass during a protest in New York, he was institutionalised and underwent electroshock treatment. Along with head trauma he had received, this caused lasting physical, psychological and spiritual damage.

Kaufman rarely spoke after this. His decade-long vow of silence, beginning in 1963, was less a reaction to John F Kennedy’s assassination (as is often claimed) than a protest against a dehumanising society that refused to see him.

How does Kaufman’s poetry bear witness to his inner world and the sociopolitical realities he was forced to navigate? His Jail Poems, written in San Francisco City Prison in 1959 – the same year he founded the literary magazine Beatitude with Ginsberg — are in dialogue with Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” (“I is an other”) and, it could be argued, W E B Du Bois’s concept of the African American’s “double-consciousness,” which arises from the conflict between an individual’s self-identity and the society’s perception of them. In the seventh Jail Poem, he states:

Someone whom I am is no one.

Something I have done is nothing.

Someplace I have been is nowhere.

I am not me.

A psychically and spiritually itinerant Kaufman ends the poem burdened by the very idea that the world sees him as “no one.. nothing... nowhere.”

“All these strange streets / I must find cities for,” he writes. “Thank God for beatniks.”

These literary outlaws — renegades, mavericks, partisans — tell us the truth. Their “authenticity” stands, as they did, outside the systems and institutions that marginalised and pathologised them. They illuminate that which we are unable or unwilling to see in society and in ourselves — and perhaps liberate us, at least momentarily, from our conditioning and self-delusions.

In this, they take us outside ourselves. In their candid and vulnerable, often idiomatic, scatological and spontaneous transmission of consciousness and experiences that are atypical, they teach us empathy and compassion. In a dehumanising society hurtling nihilistically towards its endgame, these poets’ salvation of the human — in its varying sensibilities and vulnerabilities — is indeed revolutionary.

George Mouratidis is Fellow of Literary Studies at the University of Melbourne

This is an abridged version of an article first published in The Conversation