STEPHANIE DENNISON and ALFREDO LUIZ DE OLIVEIRA SUPPIA explain the political context of The Secret Agent, a gripping thriller that reminds us why academic freedom needs protecting

KENNY MACASKILL welcomes an outstanding biography that gives full context to the life of Scotland’s greatest early 20th century novelist

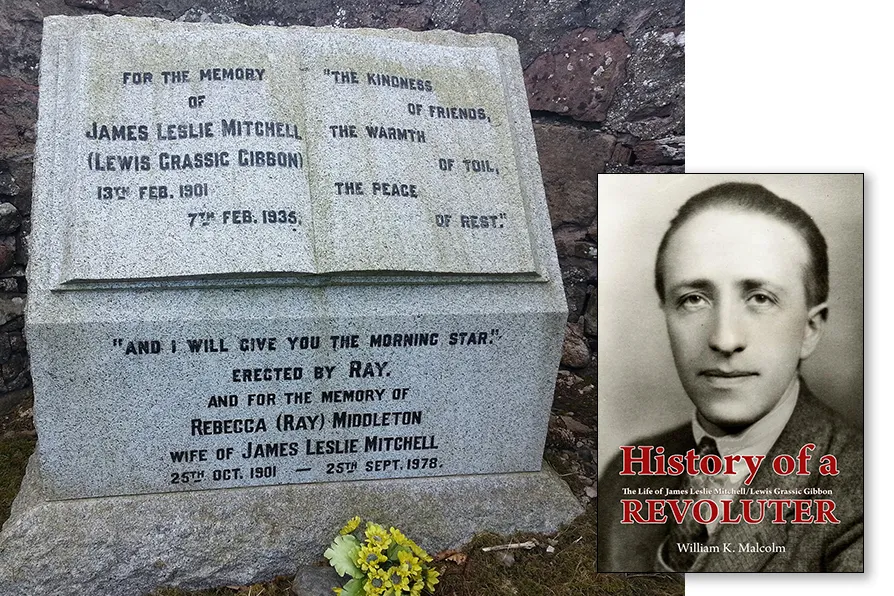

I WILL GIVE YOU THE MORNING STAR: Memorial to Lewis Grassic Gibbon in Arbuthnott kirkyard [Pic: RobHickling/CC]

I WILL GIVE YOU THE MORNING STAR: Memorial to Lewis Grassic Gibbon in Arbuthnott kirkyard [Pic: RobHickling/CC]

History of a Revoluter

William K Malcolm, Jetstone, £24.99

HISTORY OF A REVOLUTER is much more than just an enjoyable biography of James Leslie Mitchell far better-known alter ego Lewis Grassic Gibbon.

Mitchell had written several books under his birth name, including a biography of Spartacus, and would continuing doing so until the end of his all too short life, dying just a few days short of 35.

But it was as Lewis Grassic Gibbon that he really came to fame around the globe. His Scots Quair trilogy — and in particular the first book Sunset Song becoming one of Scotland’s best-loved books — making him one of the country’s most famous literary figures, translated into numerous languages, as well as appearing in celluloid on TV and cinema screens.

In that and through his other Grassic Gibbon novels life, love and labour in rural north-east Scotland were narrated, with much use being made of the native Doric language, albeit in a way easily understandable to those with no knowledge of it, let alone Scots.

His prose and use of language give an insight which couldn’t be done with standard English and certainly not received pronunciation. He provides an image not just of the topography but the hardship that the land brought with it for those eking out a living on its soil.

It was, however, neither a romanticised nor “kailyard” vision, the description given to the Lorna Doone-type portrayals of Scotland where everything’s bonnie and the folk are always cheery. Grassic Gibbon narrated life as raw, hard and not just in the work but the living. The poverty of income is matched by the austerity, and even grimness, imposed by the strict Calvinism dominating the area.

The timeline running from his birth at the turn of the century, as technology began to change farm life (albeit slowly) through the Great War with all its horrors to both combatants and communities, to the 1920s and early ’30s with challenges to the social and economic order as a working class united and a labour movement evolved and fought.

There have been previous biographies of Mitchell/Gibbon but this surpasses them all. It’s not simply the meticulous research: Malcolm met the family when doing a PhD many decades ago and remained friends with Mitchell’s widow and children throughout their lives; it’s a labour of love evidenced by Malcolm’s continuous involvement in the Grassic Gibbon Centre in Arbuthnott where Mitchell grew up.

All that has afforded unparalleled access and insight, which is matched by assiduous and scrupulous investigations and fact-checking giving context, elaborating and explaining both Gibbon/Mitchell’s writings and life.

This biography’s one which will be enjoyed by lovers of literature and Grassic Gibbon in particular but equally by those seeking an insight into the social and history of the time. For as well as providing an understanding as to why and what Mitchell/Gibbon was writing about, it also puts his works and his actions in the framework of the time.

Mitchell was unashamedly of the left, and the book suggests that he twice sought to join the Communist Party but was either rejected or didn’t follow through for whatever reason. But he worked closely with the Communist Party of Great Britain in his final years in what would be viewed as broad left organisations.

Mitchell’s political views may have been those of only a minority where he was born and reared, but it was the land and his upbringing which molded him and forged them. He can be hard on his people, but his love for them runs through his books. But, ironically, it took uprooting himself to Welwyn Garden City, where he spent his later years, for the prose to flow freely.

That it is doubtful he could have been so descriptive had he remained is shown by the discomfort, if not anger, many there felt, and some with justification when they found themselves excoriated in print, albeit anonymously. But Scotland’s a village and many knew who he alluded too.

Mitchell’s two older half-brothers were born to his mother out of wedlock. That would have affected her as, although not uncommon, it still carried a mark of shame. His father who brought all up as his own was a deeply Calvinist man, cold and hard towards his natural son. Sadly, neither parent saw the genius in their son who, despite never being close and refusing to stay and work on the farm, remained a dutiful son, visiting throughout his all-too-short life.

Though he loved the people he was undoubtedly frustrated by their stoicism and political passivity, driven no doubt by Calvinist predestination and belief in a better world, but not on this earth or in this life. This inevitably frustrated the revoluter of the book’s title who sought a social and economic revolution.

The biography discloses not just the genius but the prodigious work rate of Mitchell. Poverty had driven him into the armed forces, like so many at the time. But on his return to civvy street, and desperate to be a writer, life was still very challenging, with him and his young family existing on the borderline. There was to be no heaven on earth for him and his literary works during his lifetime, though his talents had begun to be noted. It’s what he left to posterity that has made his name and elevated him to the literary gods.

The book narrates friendships with other Scottish and British radical writers, and what he had planned to write included even a biography of William Wallace. Seventy years before Mel Gibson and Braveheart it would perhaps have been a more accurate portrayal. You’re left with a profound sadness about what might have been. So many of Scotland’s literary greats — whether Burns, Stevenson or Mitchell — were taken far too young.

This book is excellent, and will both appeal and give insight to those with interests either literary, historical or political.